The Roman Empire evolved from the Principate’s fiction of the “first citizen” to the Dominate’s openly sacral, autocratic monarchy between the late third and early fourth centuries, chiefly because repeated military crises, fiscal pressures, and political instability made the Augustan constitutional façade untenable while encouraging administrative centralization, court ceremonial, and a new hierarchy of imperial offices that concentrated power around the emperor’s person. In practice, Diocletian and Constantine formalized an absolute monarchy—signaled by titles like dominus, the diadem, proskynesis at court, and the creation or elevation of institutions such as the sacrum consistorium, the praetorian prefectures, and the magister officiorum—transforming the state from a princeps-led “res publica” into a visibly sacral emperorship with a hypertrophied bureaucracy.

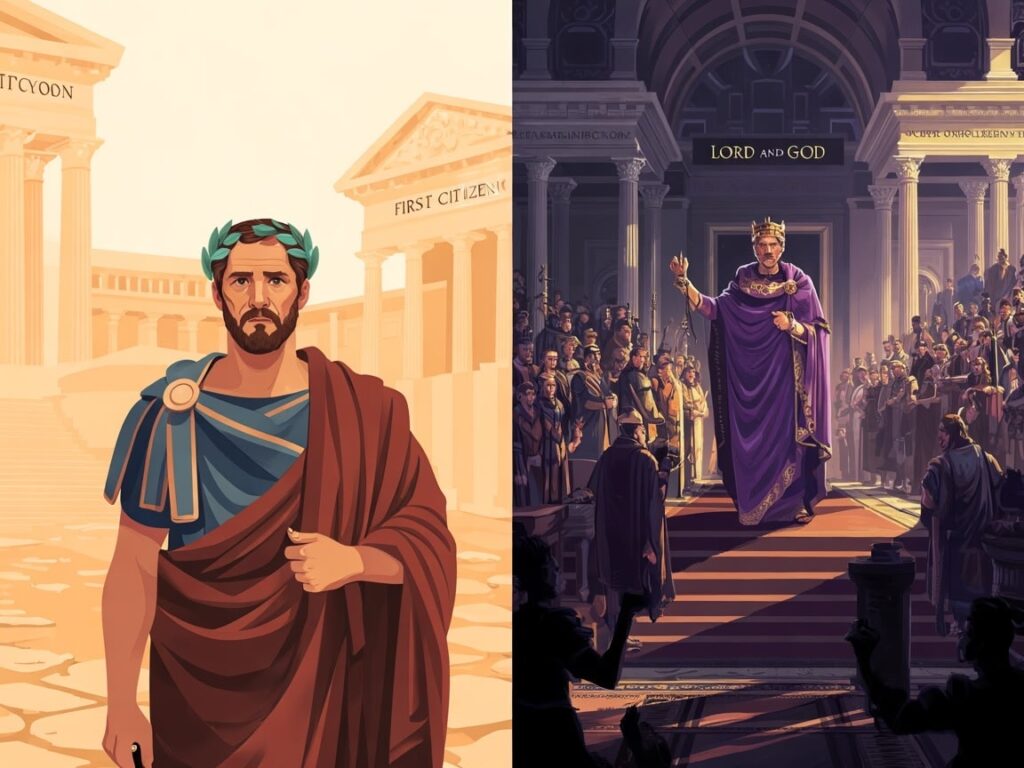

From “princeps” to “dominus”

Across the early Empire, Augustus and his successors preserved the language and some procedures of the Republic, styling the emperor as “princeps,” the “first among citizens,” even as personal imperium and control of the army made the role effectively monarchical. By the later third century, civil war, invasions, and fiscal strain eroded the credibility of that constitutional fiction, preparing the way for Diocletian’s overt embrace of autocracy and the later historiographical label “Dominate” from dominus, “lord.” Late antique authors and modern scholarship use “Principate” (27–284 CE) and “Dominate” (from 284 CE) to mark this ideological and institutional shift, though the evolution was gradual and built upon earlier trends toward centralized authority.

Why the shift mattered

The transition mattered because it changed the relationship between emperor and institutions: the senate receded from meaningful governance, military command and fiscal extraction were reorganized on more centralized lines, and political legitimacy took on a heightened sacral and ceremonial cast, reshaping elite careers and provincial administration alike. Under the Dominate, the emperor’s court and council became the nerve center of policy, lawmaking, and appointments, while the administrative map—prefectures, dioceses, and provinces—was resized and layered to tighten oversight and revenue collection. These changes produced a more formal hierarchy of dignities and offices, and a larger, more specialized bureaucracy that mediated access to the emperor and executed his “leges generales” across the Empire.

The problem the Principate couldn’t solve

Third-century instability

From the 230s to the 270s, rapid imperial turnovers, frontier incursions, and fiscal imbalance exposed structural weaknesses in succession and command, pressuring institutions crafted for a city-state republic now stretched across continents. Emperors leaned increasingly on the army and its commanders, accelerating militarization of politics and making stable, lawful succession the exception, not the rule. Efforts under the Severans to regularize administration, finance, and military recruitment foreshadowed later reforms but were insufficient to stem systemic shocks.

The end of senatorial primacy

Although senators retained prestige, practical governance shifted toward equestrian and later specialized palace officials, jurists, and prefects whose authority rested on imperial delegation rather than republican magistracies. By the time Diocletian came to power in 284, the senate’s legislative and deliberative role was marginal compared to the emperor’s council and the proliferating central bureaux. The fiction of the senate as a coequal partner had become incompatible with the demands of crisis management and empire-wide logistics.

What Diocletian changed

Tetrarchy and administrative scaling

Diocletian reorganized supreme power by associating co-emperors (Augusti and Caesares) and scaling the administrative map into more, smaller provinces grouped into dioceses under vicarii—an architecture meant to distribute command while tightening supervision and tax collection. This “layering” made provincial governors more accountable and limited their military power by separating civil from military chains of command. The aim was to reduce the risk that any single commander could pivot provincial resources into a bid for the purple while improving response times at borders.

Fiscal and legal centralization

To stabilize revenues, the regime pursued more regularized assessments and in-kind levies for feeding armies and officials, widening the reach and predictability of state demands such as the annona. Law increasingly flowed as imperial rescripts and general edicts, elevating palace jurists and chancery routines over senatorial deliberation, with the emperor’s will promulgated and archived through professionalized offices. This legal centralization aligned with the court’s enhanced role as the locus where petitions were heard and policy coordinated.

Ceremonial monarchy

Diocletian and his successors framed imperial presence with Hellenistic and Persian-inflected ritual—purple silks, jeweled shoes, a throne, prescribed audiences, and proskynesis—signaling that the emperor was no longer merely “princeps civitatis” but a sacralized sovereign. This ceremonial shift taught subjects how to approach the emperor, increasingly through formalized hierarchies and intermediaries, rather than as a magistrate among peers. The adoption of the diadem under Constantine further marked the separation of the emperor from ordinary civic identities, projecting a cultic aura to imperial rule.

The Dominate’s new machinery of power

The sacrum consistorium

Constantine’s court replaced the looser consilium principis with the sacrum consistorium, a standing high council where top officials deliberated and countersigned policy, law, and ceremonial acts. Ex officio members included the magister officiorum, the quaestor sacri palatii, the comes sacrarum largitionum, and the comes rerum privatarum; the emperor could also appoint comites consistoriani to broaden participation. The consistorium’s composition and procedures varied with emperors, but its role as the epicenter for “deliberations about political and administrative matters” and the solemn sanctioning of imperial laws was a hallmark of the Dominate.

The praetorian prefects reborn

Originally commanders of the Praetorian Guard, praetorian prefects had, by around 300, become chief administrators of the Empire, executing judicial powers vice sacra, organizing tax levies, and supervising governors. Constantine stripped the post of direct military command but retained and elevated its civil, judicial, and fiscal authority, transforming it into the highest civilian office and subdividing the Empire into regional prefectures headed by these officials. Laws were frequently addressed to specific prefects, reflecting their role as chief ministers who translated imperial policy into provincial action across the largest territorial divisions of the late Empire.

The magister officiorum

Created under Constantine, the magister officiorum became the master of central administration: overseeing palace guards (scholae), arms factories, the state courier system, foreign envoys, and the corps of agentes in rebus who monitored provincial officials and carried imperial orders. As an ex officio member of the consistorium, the magister officiorum coordinated multiple scrinia (letter offices) that drafted, copied, and archived imperial correspondence and edicts under his ultimate control. The role’s breadth made it a peer of the praetorian prefects in influence, particularly at court, cementing a dual axis of central power between the palace and the prefectures.

A hypertrophied bureaucracy

Under the Dominate, central and regional offices multiplied and specialized: comes sacrarum largitionum managed cash revenues and state industries, comes rerum privatarum administered the emperor’s private domains, and the scrinia handled the flow of letters and laws. This apparatus professionalized governance, but it also imposed layers of procedure and hierarchy, making access to the emperor dependent on office-holders and formal audiences. The effect was a larger, more routinized state whose legitimacy rested not only on military success but on the regularity of administrative and legal processes emanating from the court.

“Cérémonial oriental” and the sacral emperor

Proskynesis and the diadem

Proskynesis—prostration before the emperor—featured in late imperial audiences, emulating Near Eastern and Hellenistic court protocols and underscoring the distance between ruler and subject. The emperor’s public appearance in purple silk, with jeweled footwear and a throne, rendered monarchy as a staged, sacred presence, aligning imperial charisma with religious imagery and ritual. Constantine’s adoption of the diadem, and the increasingly choreographed court ceremonial, consolidated the monarchy’s sacral aura without eliminating older Roman idioms like the “res publica.”

Christian and traditional sacralities

Constantine’s reign layered Christian patronage onto existing sacral kingship forms, embedding bishops and Christian rhetoric in imperial events while continuing many traditional legal and administrative practices. The emperor became patron and arbiter in church affairs, yet the court’s ceremonial and bureaucratic routines remained those of a centralized, hierarchical monarchy. This synthesis reinforced the emperor’s ideological position as God’s chosen ruler without diluting the institutional centralization characteristic of the Dominate.

Offices in detail: the late imperial triangle

Praetorian prefects as chief ministers

By the fourth century, the praetorian prefects directed civil administration across vast prefectures, with powers over taxation, budgets, jurisdictions, and appeals, often issuing judgments “in the emperor’s stead” (vice sacra). Their departments were subdivided into specialized sections such as the schola excerptorum and scriniarii, reflecting the sophistication of late imperial administration. Across the divided Empire, the senior prefects (East and Italy) acted as first ministers at the emperors’ courts, while those of Illyricum and Gaul held more junior rank.

The magister officiorum and the palace

The magister officiorum coordinated palace guards, chancery, courier routes, arms production, and diplomatic protocol, sustaining the logistical and symbolic heart of imperial power. Under his ultimate control lay the scrinia epistolarum and related letter offices, which produced and authenticated imperial communications under highly formalized procedures. The agentes in rebus, answerable to him, could investigate governors and ensure compliance, giving the palace an intelligence and enforcement arm distinct from provincial hierarchies.

The sacrum consistorium as policy engine

Meeting as the emperor’s formal council, the sacrum consistorium deliberated on appointments, legal promulgations, and high policy, while providing a forum for top officials to influence decisions and stage the solemn sanctioning of laws. Its flexible membership let emperors tailor counsel to circumstances, while ensuring that the heads of finance, law, and administration were consistently present at the center of power. In this sense, the consistorium embodied the Dominate’s fusion of ceremony, law, and administration into a single, court-centered process.

“Premier citoyen” to “Seigneur et Dieu”: language and meaning

The rhetoric of rule

Under the Principate, emperors publicly styled themselves as “princeps,” with authority cloaked in republican magistracies and senatorial honors, even as the army underwrote their supremacy. Under the Dominate, address and ritual conformed to a language of lordship, with dominus as the characteristic idiom of imperial authority and the imperial household and court framed as sacra. The shift in idiom both reflected and reinforced a constitutional reality: law and administration stemmed from the emperor’s person and his courtly apparatus, not collegial republican institutions.

Latin phrases and their worlds

The Principate’s “princeps civitatis” suggested civic primacy within a republic, whereas the Dominate’s “dominus noster” and “sacrum consistorium” evoked a sovereign at the center of a sacred court and council. Titles like “praefectus praetorio” and “magister officiorum” marked the maturation of specialized offices whose power derived from imperial delegation rather than electoral legitimacy. Even as texts continued to use “res publica,” the term’s lived meaning increasingly denoted the emperor’s orderly commonwealth administered through a graded hierarchy of imperial service.

Why bureaucracy grew—and why it stuck

Scale, security, and revenue

A larger, more specialized state solved problems of scale—logistics, taxation, law, and defense—that a leaner, senatorial Principate could not reliably manage under persistent military pressure. Prefectures and dioceses distributed oversight while preserving central control, and palace offices routinized decision-making and communications across great distances. The result was a more predictable, if heavier, apparatus of extraction and enforcement that stabilized imperial finances and sustained professional armies.

Trade-offs of centralization

The late Empire’s hypertrophied bureaucracy created clearer career ladders, standardized procedures, and more uniform law, but it also increased barriers to access, procedural delays, and dependence on courtiers. Policy flowed through scripted audiences and registered acts, shifting political contestation into the dynamics of appointment, precedence, and petition within the court’s ceremonial order. Yet this very routinization helped the imperial center survive shocks that had toppled third-century regimes, making centralization a durable feature of Roman governance.

Continuities and breaks

What stayed the same

Despite ideological change, core practices persisted: provinces were governed by appointed officials; armies guarded frontiers; and imperial law remained the supreme source of public order. The senate’s social prestige and ceremonial roles lingered, and Roman legal and administrative traditions continued to frame governance even as new offices took primacy. In this sense, the Dominate built upon Roman habits of command while changing the outward forms and centers of initiative.

What truly changed

What changed was visibility and structure: monarchy shed its republican mask, court ceremonial codified access and hierarchy, and new central offices mediated every significant interaction between emperor and empire. The emperor was now not just the state’s chief magistrate but its sacral sovereign, and the court—through the consistorium and palace bureaux—became the state’s governing engine. The Dominate is therefore best understood as an explicit monarchy atop a stratified administrative system that transformed Roman politics into a court-centered process.

Key institutions at a glance

- Sacrum consistorium: Constantine’s high council, replacing the consilium principis, where the emperor staged deliberations and the solemn sanctioning of laws in the presence of top officials.wikipedia

- Praetorian prefectures: The largest administrative divisions, whose prefects served as chief ministers with judicial, fiscal, and supervisory powers, especially after Constantine’s demilitarization of the post.britannica+1

- Magister officiorum: Master of Offices, coordinating palace guards, chancery, courier system, arms factories, agents, and diplomatic protocol; a central node of court administration.wikipedia+1

- Financial counts: Comes sacrarum largitionum (state cash revenues, industries) and comes rerum privatarum (emperor’s private estates), integrating fiscal extraction and property management into court routines.wikipedia

- Scrinia: Letter offices under the magister officiorum that drafted, copied, and archived imperial correspondence and edicts, ensuring standardized promulgation of law.

Latin voice, late Roman meaning

“Res publica” survived as a term but now signified a commonwealth governed through sacral monarchy and professional offices rather than shared magistracies and senatorial deliberation. “Princeps civitatis” gave way to “dominus noster,” and the emperor’s audience became a choreographed approach to sacral power rather than a civic encounter with a primus inter pares. Titles like “praefectus praetorio” and “magister officiorum” framed careers not as municipal honors but as service in an imperial hierarchy anchored in court and council.

Conclusion: The logic of the Dominate

The Empire became an absolute monarchy because the problems it confronted—persistent military threats, fiscal strain, and administrative complexity—rewarded centralization, ritualized authority, and professionalized governance. Diocletian and Constantine turned long-running trends into a coherent system: an emperor enthroned as dominus, a court that deliberated and legislated through the sacrum consistorium, praetorian prefects who managed the vast prefectures, and a magister officiorum who synchronized the palace machinery that made the late Roman state work. In moving from “princeps” to “dominus,” Rome traded republican forms for sacral monarchy—and, for a time, gained the administrative resilience needed to rule a world of provinces through offices rather than assemblies.