Few figures in history embody the tension between individual ambition and collective destiny as vividly as Gaius Julius Caesar. To this day, the name “Caesar” conjures up images of military genius, ruthless political maneuvering, dangerous love affairs, and the dramatic tension between personal will and the inexorable forces of fate. His life reflected a paradox: the man who seemed to control the destiny of others—armies, nations, even the fate of Rome itself—was ultimately undone by forces he could neither predict nor escape.

To understand Caesar is to understand the moments that define Western history: the crossing of the Rubicon, the tragic assassination on the Ides of March, the reforms that reshaped Rome, and the legendary romance with Cleopatra. It is also to encounter timeless themes: loyalty, betrayal, ambition, reform, and the constant weight of destiny.

This exploration will trace not only the external events that shaped Caesar’s life but also the internal dramas of his choices: why he crossed the Rubicon, why he pursued Cleopatra, why he made radical reforms, and why his enemies decided that only his death could save the Republic.

The World into Which Caesar Was Born

Rome as a Republic in Crisis

When Julius Caesar was born in 100 BCE, Rome was already a republic at breaking point. The Senate was an oligarchic institution dominated by aristocratic families, while the masses increasingly demanded more representation and rights. Political violence was becoming common. Assassinations of popular leaders such as the Gracchi brothers illustrated the Senate’s willingness to use brutality to maintain control.

Caesar entered this world of turbulence knowing that his life and ambitions would involve navigating enemies as much as rallying allies. The Republic was an arena where charisma, money, military victories, and propaganda weighed as heavily as family lineage.

The Julii Family and Caesar’s Origins

Caesar’s family, the Julii, traced their ancestry back to Iulus, son of Aeneas, and hence to Venus herself. This semi-divine association gave a religious and mythical aura to the family name. Yet despite such claims, the Julii of Caesar’s time were relatively diminished in terms of political influence. Caesar inherited a noble lineage but not immense wealth. He needed power, popularity, and daring gambles to elevate himself into the front stage of Roman politics.

Caesar the Rising Star

Early Ambitions and Marriage Alliances

Caesar’s first steps in politics were marked by calculated marriages and alliances. His marriage to Cornelia, the daughter of Cinna—a key supporter of the populist leader Marius—tied him to Rome’s populares faction. This put him in direct conflict with the dictator Sulla, who ordered Caesar to divorce her. Caesar refused, demonstrating a lifelong trait: he would never surrender his autonomy to someone else’s command.

Fleeing Rome, he survived Sulla’s proscriptions through a combination of luck and persuasion. It is said that Sulla himself remarked wryly, “In this Caesar there are many Mariuses,” recognizing the fire of ambition burning in the young man.

Captivity and Audacity: The Pirate Episode

Perhaps the most telling episode of Caesar’s character came early in his career when pirates captured him in the Aegean Sea. Instead of reacting with fear, Caesar joked with them, demanded they raise his ransom, and composed poetry for them to listen to. Later, once freed, he raised a fleet, hunted down the pirates, and personally executed them. It was an audacious demonstration of his self-belief and determination to make destiny bend to his will.

First Steps into Politics

Caesar became a skilled orator and advocate at Rome’s law courts, honing his ability to sway crowds with both words and promises. His style was bold, dramatic, and carefully crafted to appeal to popular sentiments. His rise as a political leader was inevitable, but it also brought him into constant competition with other climbing figures, most notably Pompey and Crassus.

The Ambitious General

The Gallic Wars

Caesar’s governorship of Gaul provided him with the opportunity to achieve unmatched military success. Between 58 and 50 BCE, Caesar expanded Roman control deep into what is now France, Belgium, and even crossed into Britain and Germany. His victory over Vercingetorix at Alesia was a landmark in military history.

What made Caesar more than just a successful general was his ability to document his own victories. His Commentarii de Bello Gallico was not only a brilliant piece of self-advertisement but also one of the most influential works of propaganda ever written. It portrayed him as a decisive leader, merciful conqueror, and embodiment of Roman destiny.

Competition with Pompey

While Caesar built his reputation in Gaul, Pompey, once his ally, consolidated influence in Rome. The two men had been bound by the so-called First Triumvirate with Crassus, an uneasy pact brokered to balance their ambitions. But with Crassus’ death in 53 BCE and Julia (Caesar’s daughter and Pompey’s wife) dying in childbirth, the fragile alliance disintegrated. Rivalry was inevitable.

By 50 BCE, Caesar’s enemies in the Senate, fearing his return from Gaul as a triumphant general, demanded he relinquish his army before reentering Rome. For Caesar, surrendering his military power meant political extinction—and likely assassination by his enemies.

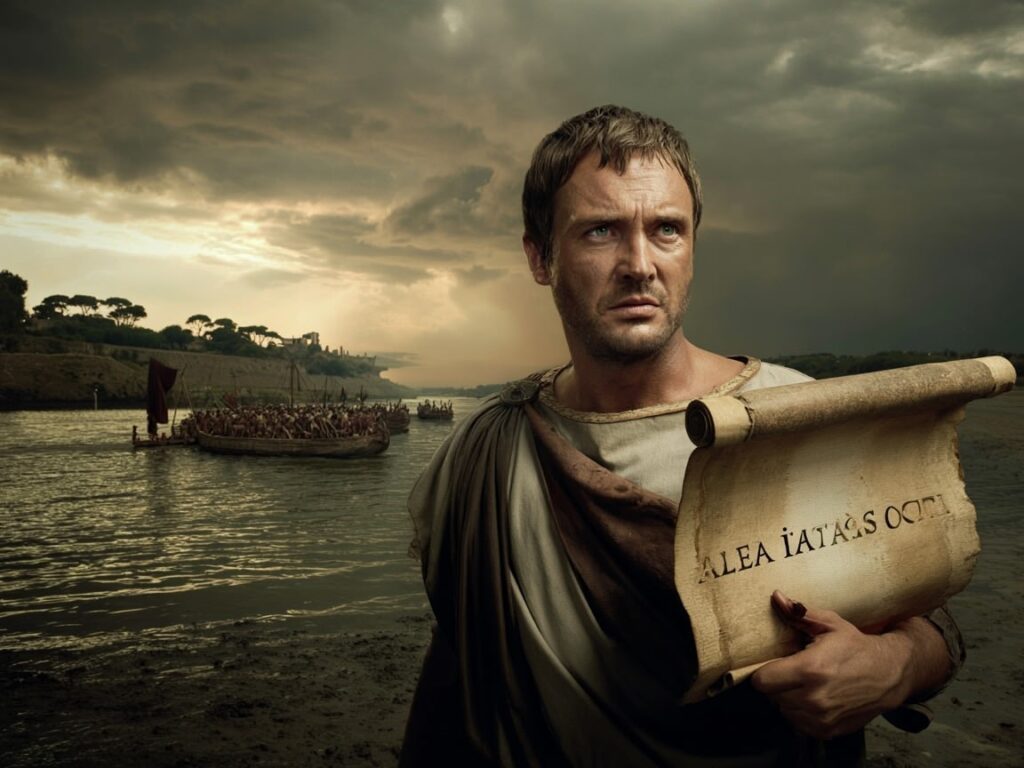

The Rubicon: A Choice Against Destiny

The Historical Context

The boundary river Rubicon separated Cisalpine Gaul from Italy proper. Under Roman law, no general could cross it with his army without committing treason. In January 49 BCE, Caesar faced the defining moment of his career: disband his army and kneel before the Senate’s hostility, or march on Rome and plunge the Republic into civil war.

“Alea Iacta Est” – The Die is Cast

Accounts tell us that Caesar hesitated before crossing, knowing full well it was an irreparable act of defiance. Once he marched, there was no turning back. “Alea iacta est,” he is believed to have said—the die is cast. With those words, Caesar forever altered the destiny of Rome.

Crossing the Rubicon symbolized more than military insubordination. It was an open challenge to centuries of Republican institutions. Yet in Caesar’s mind, it was less about reckless ambition and more about survival. His enemies would destroy him if he returned powerless. The Rubicon was simultaneously his personal dilemma and Rome’s collective turning point.

Caesar and Cleopatra: Love and Power

The Encounter in Egypt

After defeating Pompey’s forces in the civil war, Caesar pursued his rival into Egypt. Pompey was killed upon arrival, but Caesar was drawn into Egypt’s dynastic struggles. There he met Cleopatra VII, a woman of intelligence, charisma, and political ruthlessness. Wrapped in legend, their first meeting is often recounted as Cleopatra smuggling herself into Caesar’s presence rolled in a carpet.

A Relationship of Politics and Passion

Caesar’s affair with Cleopatra was more than romance—it was geopolitics. Supporting Cleopatra against her brother Ptolemy secured Rome’s influence over Egypt, one of the wealthiest regions of the Mediterranean. Their union produced a son, Caesarion, though Caesar never formally recognized him as his heir.

Cleopatra embodied the blending of Caesar’s desire for passion and political advantage. Their relationship shocked Roman elites, who viewed Cleopatra as an exotic seductress threatening Roman values.

Caesar’s Egyptian Sojourn

Caesar remained in Egypt months longer than some of his political allies thought wise, intervening militarily to secure Cleopatra’s throne. Critics later accused him of being ensnared by her charms at the expense of Roman duty. Yet for Caesar, perhaps, Cleopatra represented both an emotional escape and the embodiment of his belief in destiny: together, they presented themselves as rulers chosen by divine will.

Return to Rome: Dictator for Life

Reforms and Centralization of Power

Upon his return to Rome, Caesar began instituting sweeping reforms. These went beyond immediate stabilization and aimed at reshaping the Republic for long-term function under centralized authority.

Among his most notable reforms:

- Redistribution of land to veterans and the poor

- Expansion of Senate membership to integrate provincial elites

- Reform of the calendar, introducing the Julian calendar, which was more accurate and structured than its lunar predecessor

- Standardization of coinage and debt relief measures

- Reorganization of administrative structures in provinces

While his opponents saw these as veiled steps toward monarchy, many ordinary Romans benefited. For them, Caesar appeared more as a reformer and visionary than a tyrant.

“Dictator Perpetuo”

In 44 BCE, Caesar accepted the title of dictator perpetuo (dictator for life). To his enemies, this confirmation of absolute power was Rome’s death knell as a republic. To Caesar, however, it may have been less about titles and more about institutional order; with endless conspiracies and instability, the Republic needed firm direction.

The Assassination on the Ides of March

The Conspiracy

Caesar’s vast accumulation of authority provoked resistance. Senators who once supported him felt marginalized. Republicans such as Brutus and Cassius, influenced both by personal grievances and by the belief they were defending liberty, plotted an assassination.

The Moment of Doom

On March 15, 44 BCE—the Ides of March—Caesar entered the Theatre of Pompey for a Senate meeting. There conspirators gathered around him, concealing daggers beneath their cloaks. As they struck, Caesar reportedly resisted at first but succumbed under repeated blows. Whether or not he uttered the famous “Et tu, Brute?” remains debated, but its power lies more in the symbolic weight than historical certainty. He fell at the feet of Pompey’s statue, a grim irony as Rome’s two great rivals seemed united again by fate.

The Aftermath

The conspirators hoped Caesar’s death would restore the Republic, but their act unleashed more chaos. Far from saving liberty, it plunged Rome into further civil wars, paving the way not for republican revival but for the rise of Caesar’s heir, Octavian, who would become Augustus, Rome’s first emperor.

Caesar’s Legacy

Revolutionary Reforms

The Julian calendar remains perhaps the most enduring of Caesar’s reforms, forming the basis of the calendar we use today. His incorporation of provinces into Roman citizenship laid groundwork for expanding Roman identity beyond the city itself. These changes showed Caesar’s rare vision: that Rome’s survival required adaptation, not stagnation.

The Symbol of Fate and Ambition

Caesar left Rome not only structural reforms but also an archetype of personal destiny. His life embodied the question of how far an individual can bend history. His defiance of prohibitions, his boldness in love and war, and his final fall illustrate the paradox of ambition: necessary to achieve greatness, yet dangerous enough to provoke catastrophic downfall.

Conclusion

Julius Caesar remains one of the most captivating figures of history because he straddled the line between human and myth. He was a man of words and swords, of love and betrayal, of destiny and human choice. His romance with Cleopatra, his Rubicon decision, and his tragic assassination place his story in the realm of the timeless—part Shakespearean drama, part Greek tragedy, part Roman epic.

Above all, Caesar reminds us of the eternal conflict between individual power and collective governance. He was not a mere player in Rome’s destiny; he was the shaper of it, until destiny itself struck back on the Ides of March.