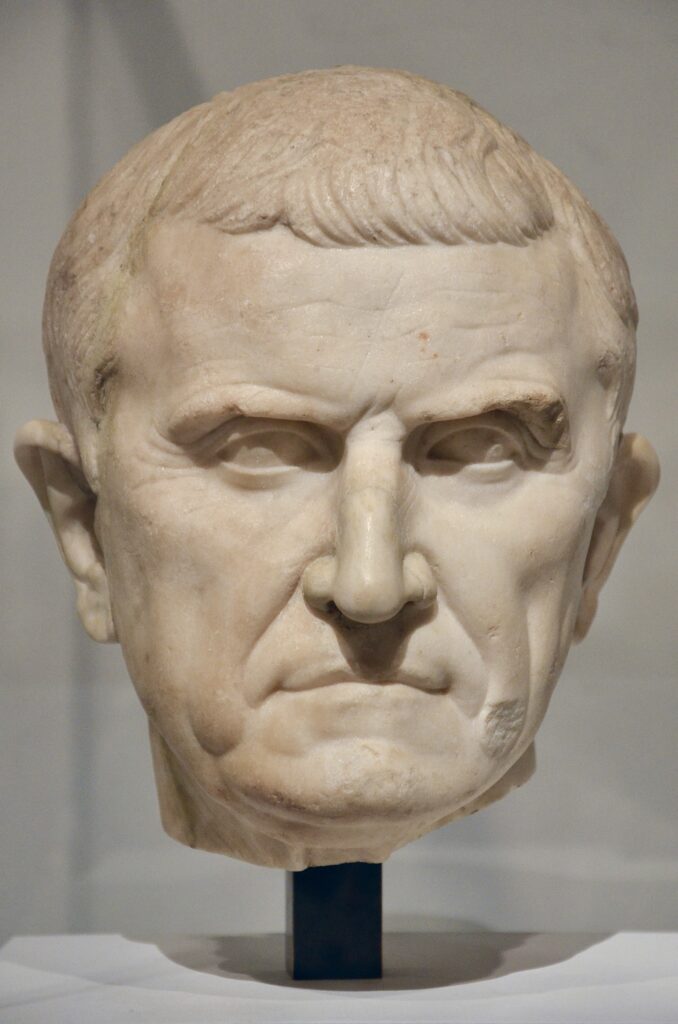

Marcus Licinius Crassus accumulated more wealth than any Roman before him, used his fortune to dominate Republican politics, and helped forge the First Triumvirate alongside Pompey and Caesar. Yet this master of money and manipulation met his end in the Parthian desert, his legions annihilated and his head reportedly used as a theatrical prop. How did Rome’s wealthiest citizen—a man who had crushed Spartacus and bankrolled Caesar’s career—come to die so far from home in pursuit of military glory he never truly possessed?

In 53 av. J.-C., somewhere in the scorching plains near Carrhae in upper Mesopotamia, Marcus Licinius Crassus watched his army disintegrate. Parthian horse archers circled his trapped legions, loosing arrow after arrow into the packed Roman formations. His son Publius lay dead, his head mounted on a Parthian lance. The tactical situation was hopeless. Within days, Crassus himself would be killed during botched surrender negotiations, his severed head sent to the Parthian king Orodes II.

The disaster at Carrhae was more than a military defeat. It represented the spectacular failure of one man’s lifelong quest to transform money into glory. Crassus had spent decades building the largest fortune in Roman history—through real estate speculation, slave trafficking, fire brigades that doubled as extortion rackets, and the wholesale plundering of proscription victims. He had used that wealth to purchase political influence, fund armies, and insert himself into the triumvirate that effectively controlled the Republic. Yet none of it could buy him what he wanted most: a military reputation to rival Pompey’s or match the ascending star of Julius Caesar.

This article traces Crassus’s extraordinary career from his family’s destruction during the civil wars through his accumulation of unprecedented wealth, his political maneuvering, his brutal suppression of the Spartacus revolt, and finally his fatal Parthian adventure. It examines the complex historiographical debates surrounding his legacy and asks what his story reveals about the intersection of money, power, and ambition in the dying Roman Republic.

The making of an oligarch: family, civil war, and the foundations of fortune

Marcus Licinius Crassus was born around 115 av. J.-C. into one of Rome’s oldest and most distinguished plebeian families. The Licinii had produced consuls, censors, and military commanders for generations. His father, Publius Licinius Crassus, served as consul in 97 av. J.-C. and later as a legate during the Social War. The family was wealthy and well-connected, but nothing in young Marcus’s early life suggested he would become the richest man Rome had ever seen.

The civil conflict between Marius and Sulla transformed everything. When Marius and Cinna seized Rome in 87 av. J.-C., they initiated a bloody purge of their enemies. Crassus’s father and elder brother were among the victims—his father reportedly committed suicide to avoid capture, while his brother was killed. The young Crassus fled to Spain, where according to Plutarch he hid in a cave on a family friend’s estate for eight months. Servants lowered food to him through a crevice; he emerged only when news of Cinna’s death made it safe to raise troops among his father’s Spanish clients.

This traumatic experience shaped Crassus profoundly. He never forgot the vulnerability of a family without adequate resources, nor the opportunities that chaos created for those bold enough to seize them. When Sulla returned to Italy in 83 av. J.-C., Crassus joined his cause and distinguished himself in the fighting. At the decisive Battle of the Colline Gate in 82 av. J.-C., Crassus commanded Sulla’s right wing and achieved the only clear victory of that desperate night engagement.

Sulla’s triumph inaugurated the proscriptions—systematized political murder combined with property confiscation on an unprecedented scale. Here Crassus found his opportunity. Ancient sources suggest he enthusiastically participated in acquiring proscribed estates, and accusations later surfaced that he had added names to the proscription lists specifically to seize their property. Whether these accusations were true or merely political mudslinging, Crassus certainly emerged from the Sullan era with dramatically expanded holdings.

The methods Crassus employed to build his fortune reveal much about both the man and late Republican Rome. Plutarch provides the most detailed account, describing a diversified portfolio that combined legitimate business with what we might call aggressive opportunism. Real estate formed the core of his wealth. Rome in this period was a crowded, chaotic city of perhaps 500,000 inhabitants, with frequent building collapses and fires. Crassus reportedly maintained a private fire brigade of 500 trained slaves. When a building caught fire, his agents would rush to the scene and offer to purchase the burning structure and adjacent properties at rock-bottom prices. Only after completing the sale would the brigade extinguish the flames. Crassus would then rebuild using his army of skilled slave craftsmen and either rent or sell the improved property.

Beyond real estate, Crassus invested heavily in slaves—not merely as labor but as capital assets. He trained slaves in lucrative skills including reading, writing, accounting, and various crafts, then either employed them directly or leased their services. He owned silver mines and agricultural land throughout Italy. He lent money at interest, though Plutarch claims he offered loans to fellow senators without charging interest—a gesture of friendship that created bonds of obligation far more valuable than any financial return.

The scale of Crassus’s wealth became legendary. Ancient sources estimated his fortune at 7,100 talents, an almost incomprehensible sum equivalent to roughly 170 million sesterces. To put this in perspective, a Roman legionary in this period earned perhaps 450 sesterces annually before deductions. Crassus’s wealth represented the annual pay of nearly 400,000 soldiers. He reportedly quipped that no one could consider himself rich unless he could maintain an army from his income alone.

Yet wealth alone did not translate into the status Crassus craved. Roman aristocratic culture valued military glory above financial success. A merchant who made millions remained socially inferior to a senator who had won a triumph. Crassus understood this calculus perfectly, which explains much of his subsequent career. He would spend decades trying to convert his economic dominance into military prestige, with fatally mixed results.

Spartacus and the shadow of victory: Crassus’s war against the slaves

The servile war that began in 73 av. J.-C. offered Crassus an unexpected opportunity for military distinction. What started as a breakout by 70 gladiators from a training school in Capua mushroomed into the largest slave revolt in Roman history. Under the leadership of the Thracian gladiator Spartacus, the rebel force swelled to perhaps 70,000 or more, defeating multiple Roman armies and ravaging the Italian peninsula for two years.

The Senate initially underestimated the threat, sending praetors with inadequate forces who suffered embarrassing defeats. By 72 av. J.-C., the situation had become critical. Both consuls took the field and failed. The rebels seemed capable of going anywhere, doing anything. Panic spread through the Italian elite, who saw their worst nightmare—armed slaves—materializing before their eyes.

Into this crisis stepped Crassus, who received command through a special appointment as praetor with enhanced powers. He raised six new legions at his own expense, supplementing the demoralized survivors of previous campaigns. His approach combined harsh discipline with methodical strategy. When one of his subordinates, Mummius, attacked Spartacus against orders and suffered defeat, Crassus revived the ancient punishment of decimation: one in ten soldiers from the offending units was beaten to death by their comrades. The message was clear—Crassus’s soldiers would learn to fear their commander more than the enemy.

The campaign that followed demonstrated competent if unimaginative generalship. Crassus pursued Spartacus southward into the toe of Italy, where the rebels hoped to cross to Sicily. When transport failed to materialize, Crassus constructed an enormous fortification across the peninsula—a ditch and wall stretching some 55 kilometers—to trap the slaves. Spartacus broke through in a winter assault but found his forces increasingly fragmented and demoralized.

The final confrontation came in early 71 av. J.-C. in Lucania. Spartacus, recognizing that defeat was inevitable, reportedly tried to kill Crassus personally in the battle, cutting down two centurions who stood in his way before being overwhelmed. The slave army was annihilated. Crassus crucified 6,000 captured rebels along the Appian Way from Capua to Rome, a grisly warning stretching for 200 kilometers.

But victory tasted bitter. Pompey, returning from Spain with his legions, arrived in time to intercept 5,000 fleeing slaves and claimed in his dispatches to have “finished” the war. The Senate awarded Pompey a full triumph for his victories in Spain; Crassus received only an ovation, the lesser honor typically granted for victories over slaves or without significant bloodshed. The injustice rankled deeply. Crassus had done the difficult, unglamorous work of defeating Spartacus while Pompey swooped in for the credit.

This pattern would repeat throughout Crassus’s career. He was consistently outmaneuvered in the competition for military prestige by more charismatic rivals. The Spartacus campaign revealed both his strengths—organizational ability, willingness to spend his own money, ruthless discipline—and his limitations. He was not a brilliant tactician or inspirational battlefield leader. His victories came through methodical application of superior resources rather than tactical genius.

The rivalry with Pompey that crystallized during the servile war would dominate Roman politics for the next two decades. Both men held the consulship in 70 av. J.-C., an awkward partnership marked by mutual suspicion. They cooperated to dismantle the remaining Sullan constitutional restrictions, including restoring tribunician powers, but neither trusted the other. Crassus reportedly kept his legions under arms near Rome until Pompey dismissed his own forces first.

Wealth as weapon: Crassus and the politics of patronage

The years following his consulship saw Crassus perfect a distinctive approach to power. Unable to match Pompey’s military reputation or popular appeal, he focused on what he did best—accumulating influence through money and patient cultivation of useful connections.

His methods were sophisticated. Crassus made himself indispensable to ambitious politicians by providing financial backing at crucial moments. The most significant beneficiary was Gaius Julius Caesar, whose early career depended heavily on Crassus’s support. When Caesar served as aedile in 65 av. J.-C., he staged spectacularly lavish public games featuring 320 pairs of gladiators in silver armor. The expense was far beyond Caesar’s personal means; Crassus reportedly covered much of the cost. When creditors prevented Caesar from leaving for his Spanish governorship in 61 av. J.-C. until he paid his debts, Crassus guaranteed the loans.

This investment paid extraordinary dividends. Caesar proved to be the most talented politician of his generation, and his gratitude to Crassus helped forge the alliance that would reshape the Republic. But Crassus spread his patronage widely. He reportedly defended anyone who asked in the courts, building a network of obligated clients across the political spectrum. He attended to small services—remembering names, attending funerals, supporting candidates—that created thousands of personal bonds.

Crassus also pursued influence through less savory means. Ancient sources implicate him in the Catilinarian conspiracy of 63 av. J.-C., though the evidence remains ambiguous. When the conspirators were exposed, Crassus was among those who received anonymous letters warning of the planned violence—convenient proof of his innocence or clever misdirection, depending on one’s interpretation. Cicero, who suppressed the conspiracy, clearly suspected Crassus’s involvement but never dared accuse him directly. Whether Crassus actually supported Catiline or merely maintained contacts across factional lines remains debated.

His relationship with Publius Clodius Pulcher illustrates his willingness to work with dangerous partners. Clodius, the radical tribune who later drove Cicero into exile, received support from Crassus at various points. The connection may have been purely transactional—Clodius was useful for destabilizing Pompey’s position—but it exposed Crassus to accusations of fostering political violence.

Throughout this period, Crassus consistently found himself overshadowed. Pompey’s extraordinary commands against the pirates (67 av. J.-C.) and Mithridates (66-62 av. J.-C.) brought him glory and wealth that even Crassus could not match. The conquest of the East made Pompey the dominant figure in Roman politics, or so it appeared. When Pompey returned in 62 av. J.-C. and disbanded his army, he expected the Senate to ratify his eastern settlements and provide land for his veterans. Instead, he encountered obstruction from optimates led by Cato and Lucullus.

This opposition created the opening for the First Triumvirate. In 60 av. J.-C., Caesar—freshly returned from a successful Spanish governorship and seeking the consulship—brokered an alliance between Pompey, Crassus, and himself. The arrangement was simple: each would use his particular resources to advance the others’ interests. Pompey provided military prestige and veteran soldiers; Crassus contributed money and his network of political clients; Caesar offered energy, ambition, and political skill.

The triumvirate was not a formal institution but a private agreement among three powerful men to coordinate their efforts. Caesar’s consulship in 59 av. J.-C. demonstrated its effectiveness. Despite fierce opposition, he pushed through legislation ratifying Pompey’s eastern arrangements, distributing land to veterans, and securing for himself an unprecedented five-year command in Gaul. Crassus received lucrative tax-farming contracts in Asia for his publicani allies and various lesser benefits.

Yet even within this alliance, Crassus occupied the weakest position. Pompey had his military glory; Caesar was rapidly acquiring his own through spectacular conquests in Gaul. Crassus remained the financier, essential but unglamorous. As he approached sixty, the prospect of dying without significant military achievements must have seemed increasingly intolerable.

The conference at Luca and the road to Parthia

By 56 av. J.-C., the triumvirate was fraying. Caesar’s command in Gaul was producing victories that threatened to eclipse even Pompey. Political opposition in Rome was mounting. Clodius and his gangs had created chaos, and former supporters were drifting away. Most dangerously, Pompey and Crassus had resumed their old rivalry.

Caesar intervened to preserve the alliance. At a conference in Luca in April 56 av. J.-C., the three dynasts renewed their partnership and divided future spoils. Pompey and Crassus would hold the consulship again in 55 av. J.-C., after which Pompey would receive Spain and Crassus would get Syria—both for five years. Caesar’s Gallic command would be extended for an additional five years. Each would have armies, provinces, and opportunities for glory.

For Crassus, Syria meant one thing: war with Parthia. The Parthian Empire, stretching from the Euphrates to modern Afghanistan, represented the only power capable of challenging Rome in the East. Previous conflicts had been limited, but Parthia’s recent civil wars and Rome’s expansion into Syria created conditions for a major confrontation. More importantly, a Parthian war offered Crassus his last chance for the military distinction that had eluded him.

The decision to attack Parthia was controversial from the start. There was no immediate provocation, no clear defensive justification. The tribune Ateius Capito reportedly pronounced ritual curses against Crassus as he departed Rome. Cicero and others questioned the wisdom of the campaign. But Crassus was determined. He had spent his entire career in the shadow of greater generals; now, at sixty, he would prove himself their equal.

He departed for Syria in November 55 av. J.-C., gathering forces as he traveled. In 54 av. J.-C., he crossed the Euphrates and conducted a limited campaign, capturing several Mesopotamian towns and leaving garrisons. The operation went smoothly, perhaps too smoothly. Parthia was distracted by internal conflicts, and Crassus faced little serious opposition. He withdrew to Syria for the winter, planning a major offensive the following year.

The campaign of 53 av. J.-C. would be his last. Crassus assembled approximately 35,000 legionary infantry, 4,000 cavalry, and 4,000 light troops. It was a substantial force but not overwhelming for the task, and critically short of cavalry—the arm most needed against Parthian tactics. He also brought his son Publius, who had served with distinction under Caesar in Gaul and commanded a contingent of Gallic cavalry.

Crassus faced a strategic choice: advance through Armenia, whose king Artavasdes offered alliance and a route through mountainous terrain unfavorable to cavalry; or march directly across the Mesopotamian plains toward the Parthian heartland. He chose the direct route, relying on the guidance of an Arab chieftain named Ariamnes who claimed to know the territory. It was a fateful decision.

Carrhae: anatomy of a disaster

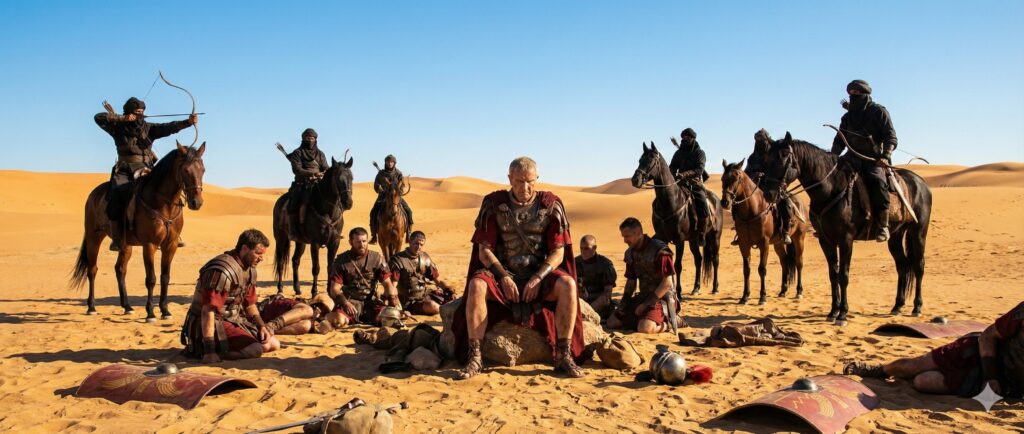

In early June 53 av. J.-C., Crassus’s army crossed the Euphrates at Zeugma and advanced into upper Mesopotamia. Almost immediately, things began going wrong. The expected Parthian main army under King Orodes II had invaded Armenia, leaving his general Surena with perhaps 10,000 horse archers and 1,000 cataphracts to shadow the Romans. Crassus learned of this division but pressed on, apparently believing Surena’s force too small to threaten his legions.

The terrain was brutal—flat, waterless, offering no cover from the scorching sun. Roman scouts reported that Ariamnes had led them away from the river into open desert. By the time Crassus recognized the trap, it was too late. Near the town of Carrhae (modern Harran in Turkey), Surena brought the Romans to battle.

What followed was a masterclass in asymmetric warfare. The Parthian horse archers refused to engage in close combat, instead circling the Roman formation and pouring in arrows from all directions. Roman infantry, trained to close with the enemy and fight hand-to-hand, found themselves helpless against opponents who stayed perpetually out of reach. The famous “Parthian shot”—turning in the saddle to shoot while retreating—made even pursuit deadly.

Crassus initially hoped the Parthians would exhaust their arrows. But Surena had prepared a camel train loaded with ammunition, allowing his archers to maintain their barrage indefinitely. The legions huddled behind their shields, unable to advance or retreat, steadily losing men to the relentless arrow storm.

In desperation, Crassus ordered his son Publius to lead the cavalry and light troops in a charge to drive off the horse archers. Publius attacked aggressively, pushing the retreating Parthians beyond a rise—and into an ambush. The Parthian cataphracts, heavily armored lancers, charged his isolated force while horse archers sealed off retreat. Publius’s command was annihilated. When his head appeared on a Parthian lance, visible to the Roman main body, any remaining hope of victory died.

The army retreated to Carrhae under cover of darkness, abandoning thousands of wounded. Crassus, according to Plutarch, was nearly catatonic with grief and shock. His officers urged continued retreat toward Armenia, but the demoralized troops could barely be controlled. Some units fled on their own, others refused orders.

Surena offered negotiations, allegedly promising safe conduct. Whether Crassus believed these promises or was pressured by his men into accepting, he agreed to meet the Parthian general. The encounter quickly turned violent—ancient sources differ on who started the fighting—and Crassus was killed. His head and hand were cut off and sent to King Orodes.

Of the roughly 43,000 men Crassus had led into Mesopotamia, perhaps 10,000 escaped to Syria. Another 10,000 were captured and settled in the distant Parthian east, where their descendants supposedly survived for generations. The rest—some 20,000—died in the campaign, making Carrhae one of the worst military disasters in Roman history.

The aftermath was almost as dramatic as the battle itself. When Orodes received Crassus’s head, he was reportedly attending a performance of Euripides’ Bacchae at the Armenian court. The actor playing Agave, who in the play displays the severed head of her son Pentheus, supposedly substituted Crassus’s actual head for the prop, reciting the relevant lines to the delight of the audience. Whether this theatrical anecdote is true or literary embellishment, it captured something essential about Crassus’s end—the man who had conquered through money died far from home, his remains become an entertainment for foreign kings.

Debating the disaster: why Crassus failed

The catastrophe at Carrhae has generated historical debate since antiquity. Ancient sources, particularly Plutarch, largely blamed Crassus personally—his greed, his incompetence, his blind ambition. Modern historians have offered more nuanced assessments, examining the structural factors that made the campaign so risky.

The question of Crassus’s generalship divides scholars. Some argue that his defeat reflected genuine military incompetence. He ignored Armenian advice about the northern route; he trusted a treacherous guide; he failed to develop tactics against horse archers; he allowed his son’s force to be isolated. These were serious errors that a more experienced commander might have avoided.

Others contend that Crassus faced an impossible tactical situation given the resources available. The Parthian system of warfare—combining mobile horse archers with heavy cavalry in terrain ideally suited to their methods—posed challenges that Roman infantry-based armies were structurally ill-equipped to meet. Later Roman commanders, including Antony and Trajan, would also struggle against Parthian tactics, suggesting the problem was institutional rather than personal.

The numbers game matters here. Crassus brought approximately 4,000 cavalry against a Parthian force that was entirely mounted. In terrain offering no natural obstacles, Roman infantry simply could not force battle against opponents who chose not to engage. The legendary discipline and fighting power of the legions became irrelevant when the enemy refused to stand and fight.

There is also the question of preparation. Crassus spent less than two years organizing his expedition, compared to the decade Caesar invested in subjugating Gaul. He conducted limited reconnaissance and apparently gathered poor intelligence about Parthian military capabilities. His logistics failed catastrophically in the Mesopotamian desert. A longer preparation period might have addressed some of these deficiencies.

Yet blaming Crassus alone obscures broader patterns. Roman expansion had always combined aggression with improvisation. Previous conquests—Greece, Carthage, Spain, Gaul—had succeeded despite limited planning because Roman military and political systems proved adaptable. Crassus reasonably expected the same formula to work against Parthia. That it did not reflected genuine limits to Roman power that only became clear in retrospect.

The political context also shaped the campaign. Crassus was sixty years old and acutely aware that his window for military glory was closing. The triumvirate had given him Syria precisely to pursue a Parthian war; backing down would have meant political humiliation and the end of his hopes for martial distinction. These pressures encouraged risk-taking that a more secure commander might have avoided.

Finally, there is the role of chance. Surena proved to be an exceptionally capable general who developed innovative tactics specifically designed to counter Roman strengths. The camel resupply system that provided unlimited arrows was apparently a new development. A less gifted opponent, or one who fought more conventionally, might have lost despite the terrain advantages. Crassus’s bad luck in facing a military genius compounded his other difficulties.

The historiographical tradition has not been kind to Crassus. Ancient sources, writing after his death and influenced by moralizing tendencies, emphasized his greed and arrogance as explanations for his fall. Plutarch’s biography, our most detailed source, systematically portrays Crassus as driven by avarice, contrasting his love of money with the nobler ambitions of Pompey and the genius of Caesar. This moralizing framework has shaped subsequent assessments, making it difficult to evaluate Crassus on his own terms.

Modern scholars have attempted to rehabilitate Crassus’s reputation to varying degrees. Allen Ward’s biography presents him as a sophisticated political operator whose methods were typical of his class and era. Frank Adcock emphasized Crassus’s genuine military abilities, arguing that Carrhae represented “bad luck more than bad generalship.” Others remain more critical, viewing Crassus as a man whose political talents exceeded his military ones—a dangerous combination when he insisted on commanding armies himself.

Aftershocks: the consequences of Carrhae

The immediate consequences of Carrhae were surprisingly limited. Surena did not exploit his victory by invading Syria; internal Parthian politics intervened. King Orodes, perhaps jealous of his general’s success, had Surena executed shortly after the battle. The Parthians made no serious attempt to hold Mesopotamian territory, and the frontier stabilized roughly where it had been.

For Roman politics, however, the effects were profound. The triumvirate died with Crassus. For years, he had served as a balancing force between Pompey and Caesar, his wealth and connections moderating the rivalry between the two greater military powers. Without Crassus, that balance collapsed.

The dynamics were simple. Pompey, remaining in Rome while governing Spain through legates, watched Caesar’s power grow with each passing year. Caesar’s conquest of Gaul brought him wealth, veteran legions, and a reputation that now matched or exceeded Pompey’s own. The two men had been connected by Julia’s marriage to Pompey, but she died in 54 av. J.-C., removing that personal bond. By 50 av. J.-C., civil war between the former allies had become almost inevitable.

Would Crassus’s survival have prevented the conflict? Probably not, but his presence might have delayed it or altered its shape. As the financier and fixer of the triumvirate, Crassus had tools for managing disputes that neither Pompey nor Caesar could match. His absence left a gap that no one else could fill.

The military consequences of Carrhae echoed for decades. The loss of the eagle standards carried by Crassus’s legions became a symbol of national humiliation that Roman leaders felt compelled to address. Augustus eventually recovered the standards through diplomacy in 20 av. J.-C., a achievement he celebrated extensively despite involving no actual fighting. The frontier with Parthia remained troubled throughout the imperial period, with major wars in the 160s and 190s apr. J.-C. that produced victories but no lasting conquest.

The captured soldiers at Carrhae entered historical legend. Ancient sources claimed they were settled in eastern Parthian territory, near modern Turkmenistan, and that their descendants could still be identified centuries later. Some modern researchers have speculated about connections between these Roman prisoners and subsequent historical developments, including the presence of Roman-style military equipment in Central Asian archaeological sites. These theories remain highly controversial and largely unproven.

Crassus’s death also had effects on Roman political culture. His career demonstrated both the power and the limits of wealth in Republican politics. Money could buy influence, clients, and armies, but it could not purchase military genius or guarantee battlefield success. The lesson was not lost on subsequent generations. Augustus, who combined political skill with genuine military ability (or at least employed able generals), constructed a system that channeled elite ambitions away from the kind of independent military adventuring that had destroyed Crassus.

The memory of Crassus became a cautionary tale about greed and hubris. Plutarch’s biography established the template: a man whose avarice led him to accumulate unconscionable wealth through exploitative methods, whose ambition drove him to seek military glory he was unqualified to achieve, and whose arrogance prevented him from recognizing his own limitations. Whether this portrait is fair—and many modern scholars doubt it—its influence on subsequent historical memory has been immense.

Conclusion: the price of glory

Marcus Licinius Crassus lived one of the most consequential lives of the late Roman Republic. He survived the proscriptions that killed his father and brother, rebuilt his family’s fortunes beyond anything his ancestors could have imagined, crushed the largest slave revolt in Roman history, and helped construct the political alliance that would ultimately destroy the Republic. His money bankrolled Caesar’s early career and influenced countless elections, trials, and political maneuverings. For three decades, no major development in Roman politics occurred without his involvement.

Yet Crassus is remembered primarily for how he died. The disaster at Carrhae overshadows everything else, reducing his complex career to a morality tale about greed and overreach. This is both unfair and revealing. Unfair because Crassus’s military failure, while catastrophic, was not obviously more culpable than defeats suffered by other Roman commanders before and after him. Revealing because it demonstrates how deeply Roman culture valued military glory over every other achievement.

Crassus understood this value system perfectly. His entire career can be read as an attempt to convert wealth—which Roman aristocrats considered slightly vulgar—into military reputation, which they revered. He succeeded once, against Spartacus, but found his victory diminished by Pompey’s self-promotion and the stigma attached to fighting slaves. He needed something more, something that would establish him definitively among Rome’s great commanders.

Parthia offered that something. A successful eastern campaign would have earned Crassus a triumph to match Pompey’s, veterans to match Caesar’s, and a reputation secure for all time. The gamble made sense in Roman terms, even if it looks foolhardy in retrospect. What Crassus could not know—what perhaps no one could know—was that the Parthian military system represented a genuine counter to Roman tactical supremacy. Against those horse archers and the flat Mesopotamian terrain, his legions were simply helpless.

The ultimate irony of Crassus’s life is that his death accomplished what his life could not: it made him memorable. Had he retired peacefully after a routine Syrian governorship, he would be a minor figure in the story of the late Republic—the rich man who bankrolled greater men. Instead, Carrhae ensured his name would be remembered as long as Rome itself. The man who spent his life chasing glory achieved it, finally, through the most spectacular failure imaginable.

His story illuminates fundamental tensions in Roman society that the Republic could not resolve. The competitive aristocratic culture that drove expansion also drove men like Crassus to take insane risks for personal glory. The system rewarded military achievement so disproportionately that even the richest man in history felt compelled to seek it, regardless of his actual abilities. And the informal arrangements—triumvirates, patron-client networks, political marriages—that held the Republic together proved fatally unstable when key figures disappeared.

Crassus did not cause the Republic’s fall. Caesar and Pompey would likely have found their way to civil war eventually, with or without him. But his career and his death reveal why that fall was probably inevitable. A political system that valued military glory above all else, in a society where private wealth could raise armies and personal ambition recognized few limits, was inherently unstable. Crassus simply demonstrated that instability more dramatically than anyone before him.

115 BC (around): Birth of Marcus Licinius Crassus in a Roman aristocratic family.

87 BC: Death of his father and brother during the purges of Marius and Cinna. Crassus flees to Spain.

82 BC: Battle of the Colline Gate. Crassus commands the victorious right wing for Sulla.

73-71 BC: Spartacus’ revolt. Crassus takes command and crushes the rebellion.

70 BC: First consulship of Crassus, shared with Pompey.

65-61 BC: Crassus finances the early career of Caesar.

60 BC: Formation of the First Triumvirate between Caesar, Pompey, and Crassus.

56 BC: Conference of Luca. Renewal of the alliance; Crassus receives Syria.

55 BC: Second consulship of Crassus with Pompey. Departure for Syria.

53 BC: Battle of Carrhae. Roman disaster; death of Crassus.

The debate on Crassus’s fortune

Ancient sources attribute to Crassus a fortune of about 7,100 talents, or roughly 170 million sesterces. These figures have sparked intense historiographical debates.

Some historians consider these estimates exaggerated, reflecting the moral rhetoric surrounding Crassus’s figure after his death. Ancient tradition tended to inflate the fortunes of men portrayed as greedy.

Others find the numbers plausible given Crassus’s sources of wealth: large-scale real estate speculation in Rome, silver mine exploitation, trade in skilled slaves, and especially the massive acquisition of properties confiscated during the Sullan proscriptions.

The question of methods remains controversial. Accusations that Crassus added names to the proscription lists to seize their assets come from hostile sources. His “fire brigades,” which bought buildings on fire, may be a literary exaggeration of actual speculative practices.

What remains certain is that Crassus had enough resources to finance private armies, support the careers of dozens of politicians, and exert lasting influence on Roman politics. His fortune, whatever its exact size, represented a new kind of political power in the Republic.

Sources

The main sources for the life of Crassus are Plutarch (Life of Crassus), Appian (Civil Wars), and scattered references in Cicero, Sallust, and Cassius Dio. Plutarch, writing at the beginning of the 2nd century AD, provides the most complete account but adopts a moralizing perspective.

Among essential modern studies are: Allen Mason Ward, Marcus Crassus and the Late Roman Republic (1977); Frank Adcock, Marcus Crassus, Millionaire (1966); and analyses of Carrhae by Gareth Sampson and other specialists in the Roman army.

The Battle of Carrhae has been reconstructed from the descriptions of Plutarch and Cassius Dio, supplemented by archaeological research on Parthian tactics and the Mesopotamian terrain. Estimates of losses vary according to sources, with the figures presented representing an approximate consensus among contemporary historians.