Few figures from ancient history embody both the brilliance of political ambition and the vulnerability of human emotion as vividly as Marcus Antonius, better known in English as Mark Antony. A celebrated general, orator, and ally of Julius Caesar, Antony possessed immense military capabilities and political influence. Yet, his enduring legacy rests not only on his triumphs in battle but also on the dramatic downfall that followed his legendary love affair with Cleopatra VII, the last ruler of Ptolemaic Egypt.

This is not merely a story about political conflict. It is about how a love affair between a Roman triumvir and a charismatic queen altered the destiny of the Roman Republic and laid the groundwork for the rise of the Roman Empire. By studying Antony’s life—his partnership with Octavian, his passionate entanglement with Cleopatra, the devastating defeat at Actium, and ultimately, his tragic suicide—we gain valuable insight into how personal relationships can dramatically transform the course of history.

Antony Before Cleopatra

Early Life and Roman Upbringing

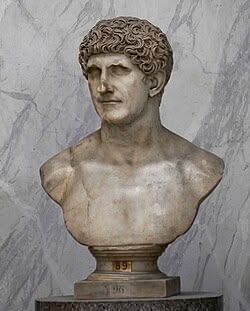

Mark Antony was born in 83 BCE into the distinguished but often troubled gens Antonia, a family that had produced important magistrates yet was known for financial difficulties. From a young age, Antony displayed a charisma that inspired both admiration and suspicion. His early years were marked by indulgence and a reputation for recklessness, yet his noble connections ensured opportunities in public life.

He studied rhetoric and philosophy, absorbing Greek education in Athens, where he refined his skills both as an orator and a soldier. These intellectual influences would later equip him with the cultural fluency to interact with leaders across the Mediterranean, including Cleopatra, who prized wit alongside political acumen.

Rise Through Caesar’s Favor

Antony’s career flourished when he attached himself to Julius Caesar. Between 57 and 54 BCE, he gained significant military experience in campaigns in Syria and Egypt, then joined Caesar in Gaul, where he commanded cavalry with distinction. It was here that Antony mastered both military leadership and the pragmatic loyalty that became his trademark.

By the time Caesar launched his civil war against Pompey in 49 BCE, Antony stood as one of his most valuable lieutenants. Appointed tribune of the plebs, Antony defended Caesar’s policies in the Senate and endured violent opposition. His fierce loyalty to Caesar ensured his survival during one of the most turbulent eras in Roman politics.

After the Ides of March

Following Caesar’s assassination in 44 BCE, Antony initially positioned himself as the natural heir to Caesar’s power. As consul that year, he delivered the funeral oration that stirred the populace and inflamed anti-conspirator sentiment. For a brief moment, Antony seemed poised to inherit Caesar’s mantle.

But his fortune soon became entangled with the ambition of another—Gaius Octavius, later called Augustus—Caesar’s adoptive son and heir. Their relationship, by turns cooperative and hostile, set the stage for both Antony’s temporary dominance and ultimate downfall.

Antony and Octavian: Allies and Rivals

Formation of the Second Triumvirate

In 43 BCE, Antony, Octavian, and Marcus Lepidus formed the Second Triumvirate, a legally recognized three-man dictatorship. Their stated goal was to avenge Caesar and restore order, but their true aim was the consolidation of personal power. Together, they initiated proscriptions, executing political enemies such as Cicero, and redistributed Roman territories among themselves.

The triumvirs won their greatest collective victory at the Battle of Philippi in 42 BCE, where they defeated the forces of Brutus and Cassius, the leading assassins of Caesar. Antony’s tactical brilliance during this campaign far outshone Octavian’s performance, cementing his reputation as the more accomplished general.

Political Division of Power

Following Philippi, the triumvirs divided Rome’s territories: Octavian governed the western provinces, Antony the eastern Mediterranean, and Lepidus Africa. This division brought Antony into closer proximity with Egypt and its queen, Cleopatra VII.

At first, Antony resisted involvement with Cleopatra and focused on campaigns against Parthia. Yet his need for resources and alliances soon brought him into contact with her, sparking one of history’s most famous love affairs.

Emerging Rivalry

Although Antony and Octavian were bound by treaty and even marriage—Antony married Octavian’s sister, Octavia, in 40 BCE—their alliance was unstable. Octavian used propaganda to portray himself as the defender of Rome’s morality while suggesting that Antony was slipping into effeminacy and treachery under Cleopatra’s influence.

As Antony grew more entangled in Egyptian court culture and fathered children with Cleopatra, his Roman critics accused him of betraying his heritage. The once formidable general who had fought alongside Caesar was increasingly portrayed as an Oriental monarch’s consort.

Octavian exploited these themes ruthlessly, ensuring that rivalry between the two triumvirs would culminate in civil war.

Cleopatra and Antony: A Legendary Love

Cleopatra’s Political Position

By the time Cleopatra VII met Antony, she had already survived fierce dynastic struggles and maintained power in Egypt through political cunning and charisma. She had borne Julius Caesar a child, Caesarion, further binding her to the fate of Rome.

Her encounter with Antony in 41 BCE came as much through design as chance. Cleopatra recognized that aligning with Antony—Rome’s master of the East—was necessary not only for Egypt’s independence but also for her own survival.

Theatrical Meetings

Plutarch recounts the legendary first meeting at Tarsus, where Cleopatra sailed up the Cydnus River in a barge adorned with gold and purple sails, presenting herself as Aphrodite incarnate. Antony, indulgent and impressed, could not resist her charms. This was not simply an affair of passion but a calculated political alliance dressed in the language of romance.

Fusion of Romance and Politics

Over the next decade, Antony and Cleopatra’s relationship deepened both emotionally and strategically. Antony spent extended periods in Alexandria, participating in Egyptian festivities and rituals, and allegedly joining Cleopatra in founding a mock society known as the “Inimitable Livers,” which indulged in feasting and revelry.

Yet beneath the pageantry lay serious politics. Cleopatra provided Antony with wealth, ships, and troops essential for his campaigns. In return, Antony legitimized her children and granted her territories once controlled by Rome, strengthening her power in the Eastern Mediterranean.

Roman Response to the Affair

In Rome, however, Antony’s actions were increasingly cast as betrayal. Octavian seized the narrative: Antony, Romans were told, had married the Egyptian queen, abandoned his Roman wife Octavia, and plotted from Alexandria to rule the world. This love affair was transformed into a symbol of decadence, corrosion of Roman virtues, and the looming threat of an “Eastern monarchy.”

Thus, what might have remained a private or dynastic union instead became the flashpoint for a clash that decided Rome’s destiny.

The Road to Actium

Antony’s Eastern Strategies

Antony’s ambitions in the East were vast. He sought to replicate Caesar’s designs for a campaign against Parthia, aiming to avenge Rome’s humiliating defeat at Carrhae in 53 BCE. However, his 36 BCE campaign ended disastrously. Harsh weather, poor planning, and inadequate supplies forced retreat, costing heavy casualties and tarnishing Antony’s military image.

Cleopatra supported him throughout these challenges, but Rome interpreted this reliance as further evidence of his subjugation to her will.

Propaganda War

The rivalry between Antony and Octavian intensified into a propaganda war. Octavian emphasized his role as defender of Italy and traditional Roman values, contrasting it with Antony’s supposed debauchery. He positioned himself as the rightful guardian of Caesar’s legacy, while Antony appeared as the foreign puppet of an ambitious queen.

Octavian’s ultimate propaganda coup came in 32 BCE, when he read aloud Antony’s alleged “Will” to the Roman Senate. According to reports, the will not only legitimized Antony’s children with Cleopatra but also left vast territories to them. Most scandalous was the suggestion that Antony desired burial in Alexandria, not Rome. Whether authentic or manipulated, the disclosure consolidated Roman hostility toward Antony.

Toward Open Conflict

By 32 BCE, diplomacy collapsed, and both sides prepared for open conflict. Cleopatra personally provided naval support, funds, and supplies. Antony and Cleopatra’s fates were now inseparably tied, not just in matters of love but in the ultimate survival of both their realms.

The Battle of Actium

Strategic Importance

The decisive confrontation between Antony and Octavian occurred at Actium in 31 BCE off the western coast of Greece. Commanding a powerful fleet, Antony benefited from Cleopatra’s Egyptian navy, while Octavian’s forces, led by Agrippa, intercepted supply routes and cornered Antony’s fleet in the Ambracian Gulf.

Tactical Disadvantages

Though Antony’s fleet was larger, it was less maneuverable. Octavian’s ships, smaller and more agile, outperformed Antony’s in open maneuvering. Moreover, Antony’s troops suffered from poor morale, desertion, and disease.

Cleopatra’s Withdrawal

The most controversial moment of the battle came when Cleopatra, with her squadron, suddenly withdrew from the fight and escaped toward Egypt. Whether this was a planned maneuver or a panic-driven retreat remains debated. Antony, abandoning tactical logic, broke from the fight to follow her.

With this act, Antony essentially surrendered the battle, leaving most of his fleet to destruction or capture.

Aftermath

The defeat at Actium decisively shifted the balance of power. Octavian emerged as Rome’s unrivaled master. Antony and Cleopatra retreated to Egypt, where they mounted a last, desperate defense. In reality, their destinies were sealed.

The Double Suicide

Antony’s Final Days

In 30 BCE, Octavian invaded Egypt. As his troops encroached upon Alexandria, Antony remained defiant yet increasingly cornered. Believing Cleopatra had taken her life, Antony fell upon his sword. Mortally wounded, he was carried to die in Cleopatra’s arms—a poignant image that dramatized the extent of his devotion.

Cleopatra’s Death

Cleopatra, taken captive, refused to be paraded in Octavian’s triumph. According to tradition, she arranged her own death by the bite of an asp, though alternative accounts suggest she employed poison. Her demise ended the Ptolemaic dynasty and cemented Egypt’s absorption into the Roman Empire.

Symbolism of Their Deaths

Their deaths gave the ancient world a tableau of tragic romance. Like mythic lovers before them, Antony and Cleopatra’s bond transcended politics, becoming a cultural symbol of passion’s collision with power.

Legacy and Historical Impact

Transformation of Rome

The fall of Antony and Cleopatra ensured the end of the Roman Republic. Octavian, absolved of rivals, inaugurated a new political order as Augustus, Rome’s first emperor. Antony’s missteps cleared the path for what would become centuries of imperial rule.

The Love That Changed History

Historians often debate whether Antony was undone by love or ambition. In truth, his relationship with Cleopatra fused both. His trust in her support extended his power, yet the perception of their union, twisted by Octavian’s propaganda, turned Rome against him.

Antony’s Legacy in Literature

Later generations immortalized Antony and Cleopatra as star-crossed lovers. From Plutarch’s Lives to Shakespeare’s Antony and Cleopatra, their romance transcended historical fact, becoming a timeless meditation on the tension between love and duty, desire and statecraft.

Conclusion

Mark Antony’s story remains captivating because it is deeply human. A general of immense skill, a politician of great ambition, and a man capable of fierce loyalty, he lost everything not purely to strategic failures but to the power of an emotional attachment. His love for Cleopatra reshaped Rome’s destiny, ending the Republic and ushering in the age of emperors.

To call him the general who lost everything for love is not to diminish his political miscalculations but to recognize how profoundly human vulnerabilities can influence the tides of history. Antony and Cleopatra remind us that even the mightiest leaders can be undone not only by their foes on the battlefield but also by the affairs of the heart.