A rising star at twenty-five, Pompey the Great reshaped Rome’s horizons from the Mediterranean to the Euphrates, only to lose the Italian heartland to his younger rival. What did he conquer, and what eluded him? This article traces how Pompey won the East, misread the West, and became the crucial foil to Caesar’s ascent.

A Shore, A Knife, A Vanishing World

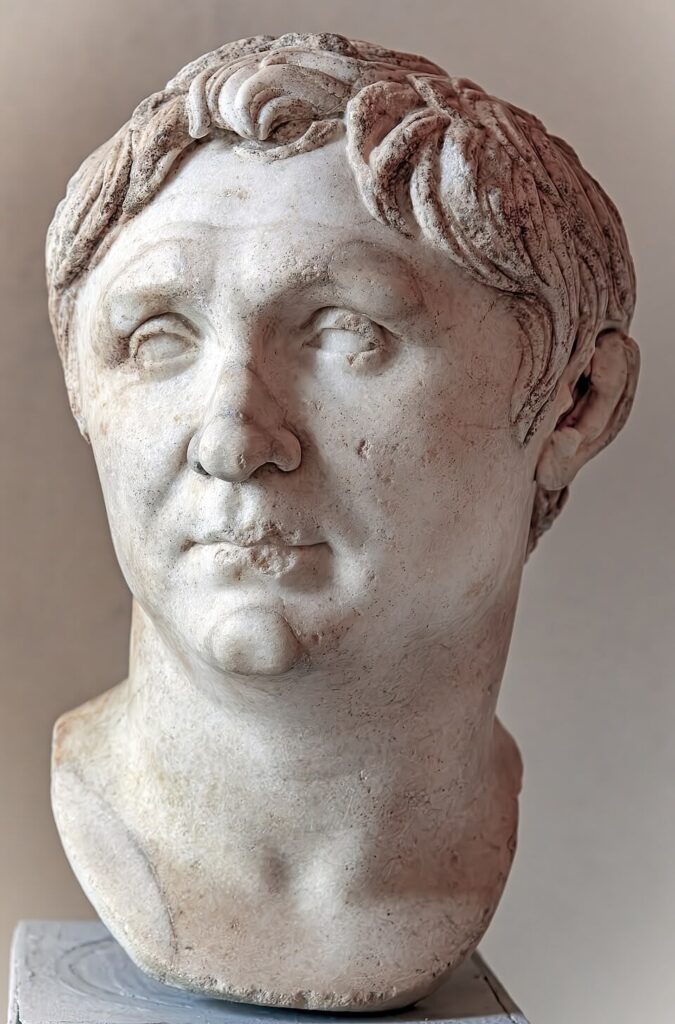

On a windswept shoreline near Pelusium in 48 av. J.-C., Pompey the Great stepped from a small boat toward a narrower future. Fleeing after the defeat at Pharsalus, he sought refuge with Ptolemy XIII’s court, confident that old treaties and his global renown still meant security. Instead, a dagger’s brief work on an Egyptian galley severed his life and his political era. This scene—plain, sordid, and irreversible—condenses a question that haunts Roman history: how did the most celebrated conqueror of his generation, the man who settled provinces and dismantled pirate empires, become the loser of Italy and a casualty of other people’s intrigues? This article argues that Pompey’s Eastern triumphs built power on legal innovation and clientage abroad, while his Western failures flowed from institutional breakdown at Rome and misjudged domestic alliances. We proceed by establishing Pompey’s political genesis, narrating the arc from his extraordinary commands to civil war, analyzing the structural forces and choices behind his defeat, engaging the historiographical controversies that recast his career, and weighing the legacies that outlived him—from Eastern settlements to Roman political precedents.

Context and Genesis: An Outsider’s Rise Within a Fracturing Republic

Pompeius Magnus began not as a pillar of the old nobility but as an equestrian prodigy from Picenum, born 106 av. J.-C. His early fame arrived by force and expedience. He raised troops on his own authority during Sulla’s civil war and, aged about twenty-three, delivered them with decisive loyalty; his enemies nicknamed him “adulescens carnifex,” the “teenage butcher,” for the severity that followed. Sulla, recognizing talent and utility, rewarded him with extraordinary opportunities. Triumphs followed fast—Sicily and Africa pacified by 81–79 av. J.-C., then Spain against Sertorius in the later 70s av. J.-C., where Pompey learned that victory at the far ends of the Republic could transform one’s leverage at Rome.

His ascent coincided with structural stress in Roman politics. Gracchan-era reforms, the Social War, and Sulla’s constitutional rewiring had loosened the bonds between senatorial consensus and military command. The result was a newly competitive market in glory, imperium, and mass appeal. Pompey thrived precisely where the old order stuttered: he accepted commands that cut across provincial boundaries (against Sertorius), and then, in 67 av. J.-C., the lex Gabinia granted him unprecedented imperium to sweep pirates from the Mediterranean. As Plutarch dryly put it, “He was made master of the sea” (Life of Pompey). In 66 av. J.-C., the lex Manilia added the war against Mithridates VI to his portfolio, again leaping over traditional assignments.

The genius of Pompey’s early career was twofold. First, he delivered spectacular results on a continental scale. Second, he used the settlements that followed to enlarge Rome’s footprint and his own clientage, especially in Asia Minor and Syria. Yet the political capital earned abroad required conversion at Rome. There, the Senate balked at ratifying his Eastern arrangements and land grants for veterans. The impasse helped forge the so-called First Triumvirate with Caesar and Crassus in 60 av. J.-C.—a workaround coalition marrying Pompey’s military fame, Crassus’s money, and Caesar’s legislative audacity. That workaround solved immediate problems and created larger ones, placing the Republic on a new track where informal power outran formal institutions.

A Documented Narrative of Ascendancy and Collapse

Pompey’s command against the pirates in 67 av. J.-C. has the crisp geometry of a strategic masterclass. Granted sweeping authority over the Mediterranean and up to fifty miles inland, he divided the sea into sectors, moved with speed, and—critically—offered clemency to those who surrendered. The campaign shocked contemporaries by its efficiency. Appian says “in forty days” he cleared the western basin and soon after the east (Mithridatic Wars). Whether the timetable is exaggerated or not, the outcome was transformative. Grain prices stabilized, shipping revived, and Pompey emerged as the Republic’s indispensable problem-solver.

The lex Manilia in 66 av. J.-C. extended that indispensability. Taking over the Mithridatic War from Lucullus, Pompey combined military pressure with political settlement. He pursued Mithridates into the Caucasus hinterlands, negotiated with regional powers, and reorganized Asia Minor. The result was an archipelago of provinces and client kingdoms designed to be governable and fiscally reliable. In 64 av. J.-C., he annexed Syria, ending the Seleucid monarchy’s hollow sovereignty. In 63 av. J.-C., he intervened in Judaea’s dynastic struggle, took Jerusalem after a siege, and entered the Temple precincts—a decision remembered as sacrilege in Jewish memory and as a marker of Roman reach in Roman memory. Cassius Dio notes the shock: “He entered even the sanctuary” (Roman History).

By 62 av. J.-C., Pompey had settled the East and could stage-manage a triumph of unparalleled breadth. When he returned in 61 av. J.-C., he sought three political commodities: ratification of his Eastern settlements, land for his veterans, and enduring authority at the center. The Senate bogged him down, fearing the scale of his achievements and the potential concentration of power. Cicero, mindful of equilibrium, maneuvered to help without abetting a new Sulla, and registered in a private letter, “Pompey is great in name; let him be great in counsel” (Letters to Atticus). The implied reservation proved prophetic.

Frustration at Rome pushed Pompey into alignment with Caesar and Crassus in 60 av. J.-C. The informal pact delivered quick returns. Caesar, consul in 59 av. J.-C., pushed through agrarian laws for Pompey’s veterans and ratified his Eastern arrangements; Pompey married Caesar’s daughter Julia, sealing the partnership with family ties. When Caesar departed for his Gallic command in 58 av. J.-C., the equilibrium persisted, albeit uneasily, as Clodius’s tribunate convulsed the city. Later, the conference at Luca in 56 av. J.-C. renewed the deal; Pompey and Crassus would be consuls in 55 av. J.-C., then hold provincial commands in Spain and Syria respectively, while Caesar retained Gaul. Pompey built Rome’s first permanent theater (55 av. J.-C.), a cultural assertion of preeminence that Civically installed him at the city’s heart.

Then, the pact unraveled. Julia died in 54 av. J.-C., fraying the personal bond; Crassus died at Carrhae in 53 av. J.-C., removing the balancing third. Street violence climaxed with the killing of Clodius in 52 av. J.-C.; Pompey, appointed sole consul, restored order with stern measures, including laws on electoral bribery and violence. Yet the role anchored him with conservative senators wary of Caesar’s ambitions. When Caesar’s command neared its end, the question became whether he could stand for the consulship in absentia and retain legal cover for his acts in Gaul. The Senate, with Pompey now its pivot, hardened. Caesar refused to abandon his imperium and risk prosecution. On a winter day in 49 av. J.-C., he crossed the Rubicon, the formula “alea iacta” later attached to him by Suetonius capturing the drama if not the exact words.

Pompey chose strategy over spectacle. He evacuated Italy, drawing forces to Epirus and Greece, trusting that time and resources would favor him. He controlled the seas; Caesar’s supply lines were precarious. The calculus was sound in principle. But at Dyrrhachium he fought Caesar to a draw tilted in his favor, then at Pharsalus in 48 av. J.-C. he accepted battle against his own instincts, pressed by senators in his camp. Caesar’s veterans, hardened by a decade in Gaul, held and counter-attacked; Pompey’s cavalry, the arm in which he sought superiority, broke. The rout ended a career built on brilliance abroad and balance at home. Flight to Egypt, an appeal to old alliance, and a conspiratorial welcome—“Pompey, the protector of our kingdom,” he had once been called—ended in a stabbing on the shore. Caesar, shown the severed head at Alexandria, reportedly turned away. Plutarch writes of Caesar’s tears; whatever their sincerity, the image signals the passing of a rival and the narrowing of the Republic’s options.

Analysis and Causality: Why the East Was Won and the West Was Lost

Pompey’s Eastern success rested on a compound of legal innovation, administrative design, and calibrated clemency. The lex Gabinia and lex Manilia created a scalable mechanism for crisis resolution: a single commander with cross-jurisdictional reach. Pompey used that mechanism less as a conqueror than as a planner. He imposed order with a mapmaker’s pen, building provinces (Bithynia et Pontus, Syria) and curating client kingdoms to buffer Roman governors. He tied local elites to Rome and to himself, knitting loyalty through arbitration, revenue regularization, and patronage. In Appian’s words, “He settled affairs in Asia” (Mithridatic Wars), a phrase less about victory than about governance.

The West was different. In Italy and the senatorial core, the mechanisms of authority—consulships, tribuneships, prorogations—had become arenas for veto and vendetta. Pompey’s power abroad had been linear; his choices produced military results and administrative settlements. At Rome, power was relational, contingent, and fragile. Three causal strands stand out.

- Institutional deadlock and the politics of exceptions. Pompey’s rise normalized extraordinary commands. What began as problem-solving—imperium over the sea and Asia—became precedential. Caesar’s Gallic governorship and subsequent claims on continued imperium drew legitimacy from that pattern. The result was a politics in which rivals competed not just for offices but for exceptions to offices. The contest had no natural stopping rule. It strained the Republic’s procedural core.

- Reliance on elite coalitions over mass mobilization. Pompey’s popularity with the people was real, but his habits were senatorial. He wanted endorsement from the establishment that resented him. Cicero saw it: “He longs for dignitas” (Letters), the blend of prestige and legitimacy that only the Senate could grant. In crisis, Pompey anchored himself in aristocratic alliance—the optimate bloc—rather than sustaining a popular machine. Caesar did the reverse. He leveraged his veterans’ loyalty and urban clients to force outcomes.

- Strategic caution versus operational audacity. Pompey’s reputation at sea and in the East was built on organization and patience. He aggregated advantages. Caesar thrived on risk compression—stacking gambles into a short time window to keep opponents off-balance. In civil war, the rhythm favored Caesar’s style. Pompey’s refusal to be rushed was sound strategy, but his coalition—senators eager for vindication, allies anxious for clarity—pushed him into battle at Pharsalus against his preference. The mismatch between his prudent instincts and the political impatience around him proved fatal.

A political economy dimension complements these strands. Pompey’s Eastern settlements generated tribute and reliable tax farming. Yet those revenues did not translate into a personal war chest independent of senatorial authorization. Meanwhile, Caesar’s conquest of Gaul produced not only political capital but also liquid wealth and veterans whose loyalty had a direct line of command. When the showdown came, Pompey had the sea and provincial allegiance; Caesar had cash, speed, and cohesion.

Finally, propaganda and narrative mattered. Caesar wrote his own war—“The die is cast”—and cast it as defense of tribunician rights and his dignitas. Pompey, despite hiring famed orators and owning a theater, could not out-narrate Caesar. Plutarch and Appian preserve a Pompey sometimes aloof, sometimes exasperated, often dignified—but not always compelling in the public square. Cicero’s private letters, sympathetic yet clear-eyed, suggest the gap: “He prefers to be the first citizen, not a tyrant,” Cicero wrote in effect (paraphrasing Att. letters), but the Republic was running out of positions between citizen and king.

Historiographical Debate and Controversies

Pompey’s career sits at a crossroads of ancient narrative and modern reinterpretation. Several debates frame how we read him.

- Was Pompey a would-be monarch or a principled republican opportunist? Ancient sources tilt both ways. Plutarch reports rumors of kingship impulses yet emphasizes Pompey’s craving for lawful honor. Cicero’s correspondence underscores his hunger for dignitas, not a diadem. Modern historians often reject the “proto-king” label, arguing that Pompey wanted primacy within republican forms, not their abolition. The theater’s dedication in 55 av. J.-C.—with its temple of Venus Victrix above the cavea—has drawn scrutiny as monarchic spectacle. Yet the project can also be read as a civic gift with self-branding, entirely at home in late-republican competition.

- The pirates: swift annihilation or managed surrender? Appian’s compressed timetable and Plutarch’s admiring tone suggest a lightning victory. Revisionist views argue Pompey combined force with incentives, relocating pirates inland as farmers and using clemency as strategy. The dramatic speed may be partly rhetorical, but the structural effect—reopening sea lanes and lowering grain prices—remains uncontested.

- The Eastern settlement: stable architecture or overreach? Robin Seager emphasized Pompey’s capacity to “settle” as an administrator, while others question whether his mosaic of client kings contained seeds of later instability. The annexation of Syria in 64 av. J.-C. ended a moribund monarchy and anchored Rome’s Near Eastern posture. Yet the Judean intervention (63 av. J.-C.), including Pompey’s entry into the Temple, provoked enduring resentment and registered Rome’s cultural insensitivity. The long-term verdict weighs toward stability in Asia Minor and Syria but recognizes the political costs at the local level.

- The Triumvirate: cynical cabal or necessary compromise? Cicero, who stayed outside the pact, dubbed it a “tresviri” arrangement undermining the Republic. Modern scholars see contingency: a Senate refusing to ratify a major commander’s settlements created incentives for an extralegal fix. The Triumvirate did not abolish institutions; it short-circuited them. In that short-circuit, precedent became practice.

- Pharsalus: tactical blunder or coalition failure? Some ancient accounts fault Pompey for not exploiting his cavalry advantage adequately, or for ordering his infantry to stand on the defensive—a choice Caesar exploited with a reserve that countered the cavalry’s flank attack (Caesar, Civil War). Others defend Pompey’s plan as solid until execution faltered under pressure. A more persuasive synthesis sees Pharsalus as the military epiphenomenon of a political dynamic: a coalition that could not sustain caution forced a decisive battle against a commander whose comparative edge lay in initiative under uncertainty.

- Egypt and the ethics of realpolitik. Was Ptolemy XIII’s counsel—largely his regents’—rational or reckless? They calculated that presenting Caesar with Pompey’s death would please the victor. Ancient writers judge the act sordid and short-sighted; Caesar himself publicly deplored it. Historiography tends to agree. The assassination eliminated a bargaining chip and entangled Egypt in Roman civil war. Caesar’s subsequent Alexandrian War underlined how quickly “cunning” can become catastrophe.

Beneath these debates lies a methodological question: how to weigh Caesar’s self-authored narrative against second-order biographers like Plutarch and compilers like Appian. A cautious approach triangulates: Caesar supplies operational detail tinted by advocacy; Cicero’s letters offer contemporaneous, private impressions; Plutarch imposes moral architecture; Cassius Dio provides institutional framing. On that composite canvas, Pompey emerges neither villain nor victim, but a political entrepreneur shaped—and finally trapped—by the Republic’s accelerating crisis.

Consequences and Legacies: What Survived Pompey

Pompey’s Eastern architecture endured. The provincial frames of Bithynia et Pontus and Syria lasted into the imperial era; his client-state logic became a standard Roman tool. Arbitration as empire-building—settling dynastic disputes to secure loyalty—remained central policy from the Armenian frontier to the Nabataean borderlands. Even criticisms of cultural insensitivity in Judea point forward to a recurring imperial tension: governance that is administratively rational but symbolically abrasive.

In domestic politics, Pompey pioneered the template of the indispensable problem-solver endowed with exceptional imperium—an office without a name but with gravitational pull. That template set precedents for Caesar’s own extraordinary commands and, later, for Augustus’s consolidation of imperium maius and tribunicia potestas within a constitutional façade. If Caesar supplied the audacity and Augustus the architecture, Pompey modeled the path by which necessity could be invoked to concentrate authority.

His loss of the West seeded afterlives. The Pompeian cause did not die at Pharsalus or Pelusium. It migrated to Spain with survivors and to Sicily under Sextus Pompey. Sextus’s maritime resistance in the 40s and 30s av. J.-C. resurrected his father’s maritime mastery, this time turning grain and sea control into leverage against the triumvirs. The contest forced Octavian and Agrippa to innovate militarily and politically—creating Portus Julius, reforming naval training, and reshaping Rome’s food supply lines. In that sense, Pompey’s legacy included the problems others had to solve.

Urban Rome bears his imprint. The Theater of Pompey structured civic life for centuries; Julius Caesar died in its precincts, an irony often noted by ancient writers. The alignment of spectacle, politics, and piety—the temple above the cavea—prefigured Augustan urban ideology. Pompey’s patronage networks, though politically defeated, survived socially, embedding families and clients who adapted to the Augustan order.

Memory did the rest. Literature and biography cast Pompey as a foil: noble, sometimes hesitant, often dignified, tragically outpaced. Lucan’s “Pharsalia” dignifies his defeat; Plutarch sketches a character study in ambition tempered by conventionality. Even Cicero, whose loyalties wavered with circumstance, could write words of admiration: “I follow Pompey because of the res publica” (paraphrasing Ad Atticum), revealing how Pompey could embody the Republic for those who feared Caesar’s concentration of power.

Yet the clearest legacy might be cautionary. Pompey’s victories abroad made Rome larger without making Roman politics safer. His career demonstrates that administrative genius and military prowess cannot substitute for institutional equilibrium. He won the East by organizing it; he lost the West by failing to organize a domestic consensus robust enough to absorb his own success.

The Republic Pompey Wanted and the One He Helped Create

Pompey the Great mastered problems that looked like puzzles—piracy, a stubborn king, an unsettled East—and he solved them with administrative grace and strategic patience. He preferred policy to drama, settlement to spectacle, honor within forms to triumph over them. But the Republic he fought to inhabit was already slipping into a politics of exceptions, where workarounds became norms and rivalries acquired armies. The First Triumvirate solved a blockage and created a breach. In that breach, Caesar moved faster, thought shorter, risked more. Pompey’s virtues—prudent, procedural, coalition-minded—became liabilities in a race that punished hesitation.

His death in Egypt in 48 av. J.-C. was not merely an end; it was a message from the periphery to the center. A client kingdom calculated wrongly about the currency of Roman power. A rival wept or performed weeping—either way, he inherited a vacuum. The institutions Pompey sought to dignify could no longer bind men of his scale to a common rule. Augustus would later stabilize what Pompey helped expose: that the Republic, as configured, could not manage global command and domestic competition simultaneously.

To remember Pompey as “the rival forgotten” is to see how overshadowing works. Caesar and Augustus wrote the next chapters, and Pompey’s pages became prologue. Yet the East Rome kept, the theater Rome used, the naval tactics Rome refined against his son—all testify that Pompey’s story is not a margin but a hinge. He conquered the East by designing it; he lost the West by believing the Republic could still design itself.

A Compressed Timeline

- 106 av. J.-C. — Birth of Gnaeus Pompeius in Picenum.

- 83–81 av. J.-C. — Rises under Sulla; campaigns in Sicily and Africa; first triumph.

- 77–72 av. J.-C. — War in Spain against Sertorius and Perperna.

- 67 av. J.-C. — Lex Gabinia grants imperium against pirates; Mediterranean secured.

- 66–62 av. J.-C. — Lex Manilia; Mithridatic War concluded; Syria annexed (64 av. J.-C.); Jerusalem taken (63 av. J.-C.).

- 61 av. J.-C. — Triumph; settlement ratification stalls at Rome.

- 60–59 av. J.-C. — First Triumvirate; marriage to Julia; Pompey’s aims legislated.

- 55 av. J.-C. — Consulship with Crassus; Theater of Pompey dedicated.

- 52 av. J.-C. — Sole consul amid urban violence; order restored.

- 49 av. J.-C. — Caesar crosses the Rubicon; civil war begins.

- 48 av. J.-C. — Pharsalus; Pompey murdered in Egypt near Pelusium.

Did Pompey Seek a Crown?

Ancient rumor trailed Pompey, especially after his third triumph and theater dedication. Plutarch notes whispers of kingship, and his temple to Venus Victrix read to some as regal pageantry. Yet Cicero’s letters depict a man craving dignitas, not a diadem. Modern scholarship largely rejects monarchic intent, stressing his insistence on senatorial ratification and lawful honors. The stronger case sees Pompey as a primus inter pares manqué—seeking first place within republican frames that could no longer hold such weight.

Sources

Primary ancient sources include Plutarch’s Life of Pompey; Appian’s Mithridatic Wars and Civil Wars; Caesar’s Civil War; Cicero’s Letters to Atticus and to Friends; Cassius Dio’s Roman History; Velleius Paterculus’s Roman History. Modern works consulted include Robin Seager, Pompey the Great; Adrian Goldsworthy, Caesar; Mary Beard, SPQR; Erich S. Gruen, The Last Generation of the Roman Republic; Catherine Steel, Cicero; and Harriet Flower, Roman Republics. Translations and interpretations follow standard scholarly editions and syntheses.