In the final decades of the Roman Republic, one commander dominated the Mediterranean world like no Roman before him. Gnaeus Pompeius Magnus swept piracy from the seas in three months, crushed Rome’s most tenacious eastern enemy, and reorganized vast territories from the Caucasus to Judaea. Yet his extraordinary career ended in ignominious betrayal on an Egyptian beach. How did the man who brought more territory under Roman control than any predecessor become the great loser of history, overshadowed by his rival Julius Caesar? The answer reveals the fatal contradictions that destroyed both Pompey and the Republic he sought to defend.

On a September morning in 48 BCE, a small fishing boat pulled alongside the trireme carrying Gnaeus Pompeius Magnus off the Egyptian coast near Pelusium. The sixty-year-old commander, once the most powerful man in the Mediterranean world, stepped aboard to meet representatives of the young pharaoh Ptolemy XIII. His wife Cornelia watched from the deck as the boat moved toward shore. Before it reached the beach, a former Roman officer named Lucius Septimius drove his sword into Pompey’s back. The assassins decapitated his body and left it floating in the shallows. The head was preserved to present to Julius Caesar, who was pursuing his defeated rival across the eastern Mediterranean.

The manner of Pompey’s death shocked the Roman world. Here was a man who had celebrated three triumphs, organized Rome’s eastern provinces, doubled the Republic’s annual revenues, and commanded the loyalty of legions from Spain to Syria. Yet his end came not in glorious battle but through treacherous murder at the hands of a client king seeking favor with his conqueror. Caesar himself reportedly wept upon receiving Pompey’s severed head and signet ring, though the gesture may have contained more political calculation than genuine grief.

Pompey’s career illuminates the fundamental tensions that tore apart the Roman Republic in its final century. His extraordinary commands—against pirates, against Mithridates, across the entire eastern Mediterranean—demonstrated that traditional republican institutions could not contain individual ambition backed by military force. His eventual defeat by Caesar proved that the Republic’s survival depended on men who possessed precisely the qualities most dangerous to its constitution. This examination traces Pompey’s trajectory from provincial strongman to Mediterranean hegemon to defeated refugee, revealing how his achievements created the conditions for his own destruction and the Republic’s collapse.

The Making of Magnus: From Provincial Origins to Sulla’s Protégé

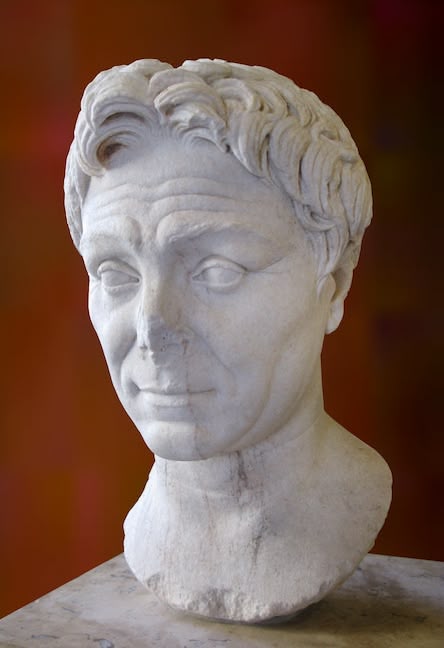

Gnaeus Pompeius Magnus was born on 29 September 106 BCE in Picenum, a region on Italy’s Adriatic coast where his family wielded considerable local influence. His father, Gnaeus Pompeius Strabo, had been the first of his branch to achieve senatorial status in Rome, completing the traditional cursus honorum and serving as consul in 89 BCE. The elder Pompey acquired a reputation for greed, political duplicity, and military competence during the Social War against Rome’s Italian allies. When Strabo died in 87 BCE—struck by lightning, according to tradition, though disease seems more likely—the Roman populace so detested him that they dragged his body from its funeral bier. Young Pompey, then nineteen years old, inherited his father’s extensive client networks in Picenum and learned early that Roman politics demanded both military prowess and political cunning.

The civil wars between Gaius Marius and Lucius Cornelius Sulla provided Pompey’s opportunity. When Sulla returned from the East in 83 BCE to reclaim Rome from the Marian faction, the twenty-three-year-old Pompey raised three legions from his family’s clients in Picenum and presented himself as an independent ally. This act was unprecedented: a young man who had never held elected office commanding a private army in support of a revolutionary cause. Sulla, recognizing both Pompey’s usefulness and his potential danger, incorporated the young commander into his forces and employed his military abilities extensively.

Sulla sent Pompey first to Sicily, then to Africa, to eliminate Marian holdouts. The campaigns of 82-81 BCE established patterns that would characterize Pompey’s entire career. He demonstrated remarkable tactical efficiency, completing both operations in lightning campaigns that crushed organized resistance. He also displayed a ruthlessness that earned him the epithet adulescentulus carnifex—’the teenage butcher’—from his enemies. Marian leaders who had surrendered received summary execution. The historian Plutarch recorded that when one such prisoner asked for a formal trial, Pompey replied that ‘the sentence had already been passed.’ This combination of military brilliance and political calculation would define his approach to power throughout his life.

It was during the African campaign that Pompey’s troops first hailed him as ‘Magnus’—’the Great’—consciously echoing Alexander of Macedon. Sulla reportedly confirmed the title, though ancient sources suggest an element of mockery in his endorsement. More significantly, Pompey demanded a triumph for his African victories, an honor traditionally reserved for magistrates commanding armies under proper authorization. When Sulla refused, Pompey allegedly told the dictator that ‘more people worship the rising sun than the setting.’ Confronted with a young commander who controlled battle-hardened legions and refused to disband them, Sulla yielded. Pompey celebrated his triumph in March 81 BCE—the first Roman to do so as a private citizen who had never held office.

The triumph itself became legendary for an embarrassing mishap: Pompey had planned to enter Rome in a chariot drawn by four elephants, symbolizing his conquest of exotic Africa. The elephants proved too large to fit through the city gates, forcing an undignified improvisation. Yet the episode illustrated Pompey’s instinct for theatrical self-promotion and his willingness to push constitutional boundaries. At twenty-five, he had demonstrated that military success could override legal constraints—a lesson that would prove fatal for the Republic.

After Sulla’s retirement and death in 78 BCE, Pompey’s position remained uncertain. He initially supported the consul Marcus Aemilius Lepidus, who attempted to reverse Sulla’s constitutional arrangements, but switched sides when Lepidus launched an actual revolt. Pompey suppressed the rebellion efficiently, then refused to disband his army, using it as leverage to secure a proconsular command in Spain against the Marian general Quintus Sertorius. This assignment, obtained without holding any of the magistracies normally prerequisite for such commands, further established the precedent of exceptional military authority granted to exceptional individuals.

The Sertorian War (76-72 BCE) proved the most challenging of Pompey’s early career. Sertorius was a brilliant commander who combined Roman tactical discipline with guerrilla methods perfectly suited to Spanish terrain. At the Battle of Lauron in 76 BCE, Sertorius outmaneuvered and humiliated Pompey, destroying a significant portion of his army. The young commander learned painful lessons about the limitations of conventional Roman tactics against an innovative opponent operating with local support. Over the following years, Pompey and his colleague Quintus Caecilius Metellus Pius gradually wore down Sertorian resistance through attrition rather than decisive victory. When Sertorius was assassinated by his own disgruntled subordinates in 72 BCE, Pompey quickly eliminated the remaining resistance and claimed credit for the victory, returning to Italy to find another opportunity awaiting him.

Pirate King and Eastern Conqueror: The Campaigns of 67-62 BCE

After suppressing the Marian rebel Sertorius in Spain through a grueling campaign from 76 to 72 BCE—during which Pompey initially suffered embarrassing defeats before wearing down his guerrilla opponent—the commander returned to Italy in time to claim credit for ending the Spartacus slave revolt, though Marcus Licinius Crassus had done most of the fighting. Elected consul for 70 BCE alongside Crassus, Pompey dismantled key elements of Sulla’s constitutional reforms and positioned himself as a moderate champion of popular causes. Then came the command that would cement his reputation as Rome’s greatest general.

By 67 BCE, piracy had reached crisis proportions throughout the Mediterranean. Operating from bases in Cilicia and Crete, pirate fleets numbering perhaps a thousand vessels disrupted trade, raided coastal cities, and even attacked Ostia, Rome’s port, where they burned ships and kidnapped two senators. The grain supply upon which Rome’s urban population depended was severely threatened. Previous commanders had achieved only temporary successes against the maritime threat.

The tribune Aulus Gabinius proposed an extraordinary solution: grant a single commander proconsular authority over the entire Mediterranean Sea and all coastal territory within fifty miles of the shore, along with the power to appoint legates, raise troops, and draw on state treasury funds. The lex Gabinia essentially placed most of Rome’s provinces under one man’s control. The Senate, recognizing the danger of such concentrated power, initially resisted, but popular pressure and the evident emergency overcame their objections. Pompey received the command—and everyone knew the law had been crafted specifically for him.

What followed was one of antiquity’s most remarkable military operations. Pompey assembled approximately 270 warships, 120,000 infantry, and 4,000 cavalry. He divided the Mediterranean and Black Sea into thirteen zones, each assigned to a subordinate commander with orders to patrol, attack pirate strongholds, and prevent escape to neighboring sectors. Pompey himself commanded a mobile strike force that swept systematically from west to east, driving pirates before him into a shrinking net.

The campaign succeeded beyond all expectations. Within forty days, Pompey had secured the western Mediterranean and the vital grain routes from Sicily, Sardinia, and Africa. Within three months, he had crushed pirate resistance throughout the entire sea, culminating in a final assault on their strongholds in Cilicia. Ancient sources record the capture of 846 ships, the destruction of 120 fortified bases, and the taking of some 20,000 prisoners. Perhaps most remarkably, Pompey showed unexpected clemency. Rather than executing or enslaving the captured pirates—standard Roman practice—he resettled them inland in depopulated towns across Asia Minor, transforming former enemies into productive subjects. The policy demonstrated sophisticated understanding of imperial administration: eliminating the social conditions that bred piracy served Rome better than mere punishment.

Before Pompey could savor his triumph, a new command beckoned. The Third Mithridatic War against King Mithridates VI of Pontus had dragged on since 73 BCE. Lucius Licinius Lucullus had achieved significant victories but could not deliver a decisive conclusion; his troops were exhausted, his political support had evaporated, and Mithridates had recovered much of his kingdom. In 66 BCE, another tribune, Gaius Manilius, proposed transferring the eastern command to Pompey with even broader powers than the lex Gabinia had granted. The Senate, despite deep misgivings, again acquiesced.

Pompey’s eastern campaign lasted from 66 to 62 BCE and fundamentally reshaped the Mediterranean world. He first moved against Mithridates, employing superior logistics and relentless pressure rather than seeking dramatic battle. At the River Lycus in 66 BCE, Pompey’s legions crushed the Pontic army in a night assault, killing over 10,000 men while Mithridates escaped with only 800 horsemen. The king fled north to his possessions around the Black Sea, where he would eventually die by suicide in 63 BCE after being betrayed by his own son Pharnaces.

Pompey then embarked on a systematic reorganization of the entire eastern Mediterranean. He reduced Armenia to client status after King Tigranes the Great surrendered and literally prostrated himself, offering his crown in a calculated display that Pompey stage-managed for maximum effect. Tigranes received back his kingdom minus significant territory and indemnity payments totaling 6,000 talents—approximately 150 tons of silver. Pompey led punitive expeditions through the Caucasus against the Iberians and Albanians, advancing further east than any Roman army before him. He created new provinces in Bithynia-Pontus and Syria, abolished the decrepit Seleucid dynasty, and established a network of client kingdoms from the Black Sea to the Red Sea.

The Syrian settlement and subsequent march into Judaea would have lasting consequences. Pompey intervened in a dynastic dispute between the Hasmonean brothers Hyrcanus II and Aristobulus II, ultimately besieging Jerusalem for three months in 63 BCE. When the Temple Mount fell, Pompey entered the Holy of Holies—the first gentile to do so—though he left the Temple treasury untouched. The incident marked Rome’s first major cultural clash with Jewish monotheism and foreshadowed tensions that would culminate in the Jewish revolts of later centuries. Pompey reduced Judaea to a client state, stripped away its coastal cities and the Decapolis, and restructured the region’s political geography in ways that endured for generations.

Pompey returned to Italy in December 62 BCE and took a step that astonished contemporaries: he disbanded his army immediately upon landing at Brundisium. Those who feared he would march on Rome as Sulla had done two decades earlier found their anxieties unfounded. Pompey sought to achieve supremacy through constitutional means, expecting that the Senate would ratify his eastern settlements and provide land grants for his veterans. In this expectation, he was bitterly disappointed. The optimates, led by figures like Cato the Younger and Lucius Lucullus (whose eastern command Pompey had taken), blocked his measures at every turn. They feared his power and resented his success; constitutional scruples provided convenient justification for political obstruction.

This senatorial intransigence drove Pompey into alliance with two men he might otherwise have opposed. Marcus Licinius Crassus, Rome’s wealthiest citizen, sought military command to match Pompey’s glory. Gaius Julius Caesar, returning from a governorship in Spain, needed support for his consular candidacy and desired a military command that would establish his own reputation. In 60 BCE, these three formed what historians call the First Triumvirate—though the term itself is modern, and the arrangement had no official status. The alliance was cemented by Caesar’s marriage of his daughter Julia to Pompey, a union that proved surprisingly happy and served as the personal bond holding the political arrangement together.

During Caesar’s consulship of 59 BCE, the triumvirate achieved its immediate objectives. Caesar pushed through legislation ratifying Pompey’s eastern settlements and providing land for his veterans, using the support of Pompey’s veterans to intimidate senatorial opposition. Caesar then obtained a five-year command in Gaul, which he would use to build the military reputation and personal army that would eventually challenge Pompey’s primacy. The alliance was renewed at the Conference of Luca in 56 BCE, with Pompey and Crassus receiving consulships for 55 BCE and subsequent military commands: Spain for Pompey (which he governed through legates while remaining in Rome), Syria and a war against Parthia for Crassus.

The triumvirate began unraveling with Julia’s death in childbirth in 54 BCE. The personal bond between Pompey and Caesar dissolved with her, leaving only political calculation to maintain their relationship. Crassus’s death at the Battle of Carrhae in 53 BCE, where his army was annihilated by Parthian horse archers, removed the third member of the alliance and the figure who had often mediated between the other two. Pompey and Caesar now stood face to face, their relationship increasingly adversarial as Caesar’s spectacular successes in Gaul challenged Pompey’s status as Rome’s preeminent commander.

The Mechanics of Power: Analyzing Pompey’s Strategic Method

Pompey’s extraordinary success derived from several interconnected factors that distinguished him from contemporary commanders. First, he possessed genuine organizational genius. The pirate campaign demonstrated his ability to coordinate complex operations across vast distances, dividing forces among trusted subordinates while maintaining strategic coherence. This capacity for systematic planning contrasted with the more improvisational approach of commanders like Caesar, who relied heavily on tactical brilliance and personal charisma to overcome logistical disadvantages.

Second, Pompey understood the political dimensions of military command. His clemency toward defeated pirates and his careful treatment of eastern client kings reflected sophisticated imperial thinking. Rather than extracting maximum short-term tribute, he sought stable arrangements that would generate reliable long-term revenue while minimizing the need for continued military intervention. The eastern settlement he created in 62 BCE added 12 million subjects to Rome’s domain, incorporated over 1,500 cities into the imperial system, and doubled the Republic’s annual revenues from 200 to 340 million sesterces. These administrative achievements arguably exceeded his military victories in long-term significance.

Third, Pompey cultivated extensive patronage networks that extended Roman influence through personal relationships rather than formal structures. His eastern clients—kings, cities, communities—looked to Pompey personally for protection and advancement. This personalization of imperial power was simultaneously his greatest strength and the source of considerable senatorial anxiety. When Pompey returned to Italy in 62 BCE, he commanded not merely an army but an entire system of dependencies stretching from Spain through the eastern Mediterranean to the Caucasus.

Yet Pompey’s methods also revealed significant limitations. He excelled at overwhelming force and methodical pressure but lacked the tactical imagination that characterized history’s greatest battlefield commanders. Against skilled opponents like Sertorius in Spain, he struggled to achieve decisive victories and required years of attrition warfare. His caution, while often prudent, could shade into excessive passivity when bold action was required. As one ancient source observed, he was ‘the perfect administrator’ rather than a military genius in the mold of Alexander or Hannibal.

More fundamentally, Pompey never resolved the contradiction between his ambitions and his constitutional conservatism. He sought primacy—to be acknowledged as Rome’s foremost citizen—but shrank from the revolutionary action necessary to secure that position permanently. Unlike Sulla, he would not make himself dictator; unlike Caesar, he would not gamble everything on a march against Rome. His preference for passive maneuvering and waiting for crises to compel others to grant him authority worked brilliantly against foreign enemies but poorly in Rome’s cutthroat domestic politics.

The extraordinary commands that made Pompey great also created precedents that undermined republican government. The lex Gabinia and lex Manilia demonstrated that popular assemblies could override senatorial opposition to grant unprecedented powers to favored commanders. Pompey’s career proved that military success trumped constitutional norms. Every ambitious general who followed—Caesar above all—had his example to guide them. In seeking to save the Republic through exceptional measures, Pompey helped establish the patterns that would destroy it.

The drift toward civil war accelerated after 52 BCE, when Pompey served as sole consul during a period of urban violence in Rome. Increasingly aligned with the optimates, he supported legislation requiring candidates for office to appear in person, which would force Caesar to lay down his command before standing for election—exposing him to prosecution for his allegedly illegal acts as consul in 59 BCE. Caesar sought compromise, offering various arrangements that would protect his position, but hardliners in the Senate, backed by Pompey, refused any accommodation. On 7 January 49 BCE, the Senate passed the senatus consultum ultimum, declaring a state of emergency and authorizing action against Caesar.

Caesar responded by crossing the Rubicon River with a single legion on 10 January 49 BCE, uttering the famous words ‘alea iacta est’—the die is cast. The speed of his advance caught Pompey and the Senate unprepared. Rather than defend Rome, Pompey chose to evacuate to Greece, where he could draw on the vast resources of the eastern provinces he had organized and the client networks he had established. Critics accused him of abandoning Italy without a fight; supporters argued he was refusing to shed Roman blood unnecessarily and positioning himself for ultimate victory. The decision remains controversial among historians.

In Greece, Pompey assembled an army of approximately 45,000 infantry and 7,000 cavalry, drawn from veterans, levies from eastern client kingdoms, and Roman citizens resident throughout the Mediterranean. His force significantly outnumbered Caesar’s approximately 22,000 infantry and 1,000 cavalry. More importantly, Pompey controlled the sea and could threaten to strangle Caesar’s supply lines. Yet the campaign demonstrated the limitations that had always constrained Pompey’s generalship: caution that shaded into passivity, an inability to seize the initiative when opportunity presented itself.

At Dyrrhachium in 48 BCE, Pompey successfully defended against Caesar’s attempted siege, even inflicting a significant tactical defeat that forced Caesar to withdraw inland. It was perhaps Pompey’s greatest moment of the civil war. Yet he failed to press his advantage, allowing Caesar’s demoralized army to escape and regroup. His subordinates and senatorial allies, overconfident after Dyrrhachium, pressured him to seek a decisive engagement. Sertorius, before his assassination, had reportedly said of Pompey that ‘if this old woman [Metellus] had not come up, I would have whipped that boy soundly and sent him to Rome.’ The epithet ‘boy’ may have been unfair to Pompey’s genuine abilities, but his hesitation at critical moments gave substance to such criticisms. On 9 August 48 BCE, the two armies met at Pharsalus in Thessaly.

The Battle of Pharsalus demonstrated the qualities that made Caesar Rome’s supreme military commander. Outnumbered but commanding veterans of nearly a decade’s continuous campaigning in Gaul, he employed innovative tactics to neutralize Pompey’s cavalry advantage, then crushed the infantry line with a coordinated assault. Pompey’s army—larger but less experienced, its components less cohesive—collapsed. According to Caesar’s own account, perhaps inflated, some 15,000 Pompeians died and 24,000 surrendered; his own losses were minimal. Pompey himself, witnessing the destruction of his army, fled the battlefield without attempting to rally his forces. His passivity in the face of disaster confirmed the judgment of those who questioned whether his abilities matched his reputation.

Defender of the Republic or Agent of Its Destruction? The Historiographical Controversy

Ancient assessments of Pompey varied dramatically depending on authors’ political sympathies and proximity to events. Caesar’s own commentaries, while ostensibly respectful, portrayed his rival as hesitant, reactive, and politically naive. The poet Lucan, writing a century later, elevated Pompey into a tragic defender of republican liberty against Caesarian tyranny. Plutarch, in his parallel biography comparing Pompey to the Spartan king Agesilaus, emphasized both his military achievements and his fundamental decency while criticizing his political inconsistency.

Cicero’s surviving correspondence provides the most intimate contemporary perspective, though one colored by the orator’s notoriously volatile judgments. Cicero’s published speeches praised Pompey extravagantly, while his private letters alternated between admiration, frustration, and contempt. In one famous passage, Cicero described the impending civil war as ‘a struggle between two kings, in which defeat has overtaken the more moderate king, the one who is more upright and honest.’ Yet he also complained bitterly about Pompey’s political obtuseness and his failure to give Cicero the recognition he believed he deserved.

Modern scholarship has largely moved beyond simple characterizations of Pompey as either republican hero or proto-imperial villain. The German historian Matthias Gelzer’s foundational 1949 biography emphasized Pompey’s role within Rome’s aristocratic political system, analyzing his career through the lens of factional competition and patronage networks. Robin Seager’s English-language political biography, first published in 1979 and revised in 2002, similarly focuses on institutional and political factors while acknowledging the limitations of approaching ancient biography through modern analytical frameworks.

Recent scholars have increasingly examined Pompey within broader frameworks of Mediterranean history and Roman imperialism. His eastern settlement, rather than being treated merely as background to domestic political struggles, has received attention as a crucial moment in the formation of Roman imperial structures. Historians note that the provincial organization Pompey established in the 60s BCE provided the administrative framework that later emperors would refine but essentially maintain. From this perspective, Pompey appears less as a failed republican than as an architect of empire whose achievements were consolidated by his successors.

The debate over Pompey’s political competence remains particularly contentious. Some historians argue that his passive strategy during the crisis of 50-49 BCE reflected reasonable caution rather than weakness: he correctly calculated that time favored him as Caesar’s command expired and his political isolation deepened. Others contend that his failure to act decisively when Caesar crossed the Rubicon—abandoning Rome and Italy without a fight—represented catastrophic miscalculation that squandered his advantages and demoralized potential supporters. The historian Florus captured the ambiguity in a memorable phrase: ‘Pompey could not brook an equal, or Caesar a superior.’ The question of whether Pompey could have preserved the Republic had he been more aggressive, or whether the system’s contradictions made its collapse inevitable regardless of individual choices, continues to generate scholarly disagreement.

Perhaps the most significant recent development has been increased attention to Pompey’s contemporary reputation and self-presentation. His adoption of the title ‘Magnus,’ his theatrical triumphs, his construction of Rome’s first permanent stone theater—all reflected sophisticated understanding of public image in an age before mass media. Pompey pioneered techniques of political branding that later leaders, from Caesar to Augustus, would develop further. Understanding him requires attending not only to his actual achievements but to the carefully crafted narrative he constructed around them.

The Long Shadow: Pompey’s Legacy in Imperial Rome and Beyond

The immediate consequence of Pompey’s defeat and death was Caesar’s unchallenged dominance over the Roman world. Yet Pompey’s legacy extended far beyond his personal fate. His sons Gnaeus and Sextus continued resistance from Spain and the western Mediterranean for years after their father’s murder. Sextus Pompey proved particularly troublesome, controlling Sicily and threatening Rome’s grain supply until his final defeat by Marcus Agrippa in 36 BCE. The Pompeian cause attracted republicans, opportunists, and all those opposed to Caesarian dominance, demonstrating the continued potency of Pompey’s name decades after his death.

More significantly, the administrative structures Pompey created in the East proved remarkably durable. His provincial organization of Bithynia-Pontus, Syria, and surrounding territories provided the framework for Roman rule for centuries. The client kingdoms he established—including the Herodian dynasty in Judaea—survived in various forms into the imperial period. His method of combining direct provincial administration with dependent allied states became the standard model for Roman imperial governance. In this sense, Pompey was less a failed republican than a successful empire-builder whose achievements were consolidated by those who defeated him politically.

The legal precedents established by Pompey’s extraordinary commands had even more profound constitutional implications. The lex Gabinia’s grant of sweeping powers over a defined sphere of operations served as the model for Augustus’s ‘greater proconsular authority’ (maius imperium proconsulare) in the constitutional settlement of 23 BCE—one of the foundations of imperial power. The ability to appoint subordinate legates, draw on public funds, and make war and peace without senatorial approval: all features of Pompey’s eastern command, all features of the principate. The revolutionary powers the Senate reluctantly granted to meet emergency became, under Augustus, permanent instruments of autocratic rule.

Pompey’s physical legacy in Rome included the first permanent stone theater in the city, completed in 55 BCE and remaining in use for centuries. The Theater of Pompey complex, which included gardens and meeting halls, became a cultural landmark and, ironically, the site of Caesar’s assassination in 44 BCE. The structure demonstrated both Pompey’s wealth and his understanding of popular politics: providing the Roman people with entertainment facilities on an unprecedented scale.

In Roman historical memory, Pompey occupied a complex position. He was neither simply villain nor hero but rather a cautionary figure whose career illustrated the Republic’s fatal contradictions. The poet Lucan’s Pharsalia, written during Nero’s reign, transformed Pompey into a symbol of lost republican virtue, a noble but doomed defender of liberty against Caesarian tyranny. This literary apotheosis, however tendentious, ensured Pompey’s continued presence in Western political imagination. Medieval and early modern writers drew on his example when discussing the dangers of civil war and the proper limits of military power.

The assassination of Caesar in 44 BCE—ironically in a hall attached to Pompey’s theater—brought a temporary revival of the Pompeian cause. The assassins included men who had fought for Pompey at Pharsalus and hoped to restore the Republic he had claimed to defend. Yet the subsequent civil wars demonstrated that the Republic was beyond revival. Augustus, who emerged victorious from these conflicts, built his principate partly on foundations Pompey had laid: provincial administration through personal legates, client relationships extending across the Mediterranean, concentration of military authority in a single commanding figure. The emperor even restored Pompey’s statue in the theater complex, acknowledging the connection between his own position and Pompey’s precedents.

The irony of Pompey’s historical reputation is that he is remembered primarily as Caesar’s defeated rival rather than as the architect of Rome’s eastern empire. His genuine achievements—the elimination of Mediterranean piracy, the subjugation of Mithridates, the organization of vast territories—tend to be overshadowed by his final failure. Yet without Pompey’s campaigns, Rome’s eastern dominion might have taken very different form. His career demonstrated both the possibilities and the dangers of concentrated military command in a republic theoretically governed by collective aristocratic leadership. In seeking to master the system, he helped create the conditions that made such mastery impossible to resist.

Conclusion

Pompey the Great embodied the contradictions that destroyed the Roman Republic. He rose through exceptional commands that bypassed traditional constitutional constraints, accumulated unprecedented personal power and patronage, and fundamentally reshaped Rome’s empire. Yet he consistently sought legitimacy through established institutions, recoiled from revolutionary action, and ultimately proved unable to defend either his own position or the republican system he claimed to champion.

His military achievements were genuine and substantial. No Roman before him had cleared piracy from the Mediterranean, defeated so formidable an enemy as Mithridates, or reorganized such vast territories. The eastern settlement he created in 63-62 BCE added more to Rome’s empire than any previous commander and established administrative structures that endured for centuries. His career demonstrated that Roman power, properly organized and led, could dominate the entire Mediterranean world and beyond.

Yet those same achievements created the conditions for Rome’s political transformation. The extraordinary commands granted to Pompey established precedents for concentrating military authority in single individuals. His client networks demonstrated how personal loyalty could substitute for constitutional authority. His triumphs showed that military glory could override legal constraints. Every subsequent Roman commander who sought supreme power—Caesar, the triumvirs, Augustus—walked the path that Pompey had blazed.

The tragedy of Pompey’s career was not merely personal but institutional. He wanted to be first among equals in a system designed to prevent any individual from achieving lasting dominance. When that system’s contradictions finally exploded into civil war, he discovered that the military power he had accumulated was insufficient against a more ruthless and tactically brilliant opponent. His death on an Egyptian beach marked not just the end of a remarkable career but the effective conclusion of the Roman Republic as a functioning political system.

Cicero’s observation that Pompey’s ‘life outlasted his power’ captures something essential about his historical position. The systems he helped create—concentrated military command, personal imperial administration, theatrical political self-presentation—survived and flourished under the emperors who followed. The Republic he sought to defend did not. Pompey was, in the end, both architect and victim of Rome’s transformation from aristocratic republic to military autocracy.

Timeline: Key Dates in Pompey’s Career

| Date | Event |

| 106 BCE | Birth in Picenum (29 September) |

| 83 BCE | Raises three legions in Picenum; joins Sulla |

| 82–81 BCE | Campaigns in Sicily and Africa; receives title ‘Magnus’; first triumph |

| 76–72 BCE | Sertorian War in Spain |

| 70 BCE | First consulship (with Crassus); second triumph |

| 67 BCE | Lex Gabinia; clears Mediterranean of pirates in three months |

| 66–62 BCE | Eastern campaigns; defeats Mithridates; reorganizes provinces and client kingdoms |

| 63 BCE | Siege and capture of Jerusalem; annexation of Syria |

| 61 BCE | Third triumph in Rome (September 28–29) |

| 60 BCE | Formation of First Triumvirate with Caesar and Crassus |

| 55 BCE | Second consulship (with Crassus); completion of Theater of Pompey |

| 52 BCE | Sole consulship during crisis in Rome |

| 49 BCE | Caesar crosses Rubicon; Pompey evacuates Italy to Greece |

| 48 BCE | Defeat at Pharsalus (9 August); assassination in Egypt (28 September) |

Scholarly Debate: Was Pompey a Republican or a Proto-Emperor?

The question of whether Pompey sought to preserve or transform the Roman Republic has generated extensive scholarly disagreement. The ‘republican’ interpretation, associated with historians like Erich Gruen, emphasizes Pompey’s consistent deference to constitutional forms: he disbanded his armies after each campaign, sought senatorial approval for his settlements, and allied with the optimates against Caesar’s revolutionary challenge. From this perspective, Pompey’s extraordinary commands were emergency responses to genuine crises rather than steps toward autocracy.

The ‘proto-imperial’ interpretation, developed by scholars including Ernst Badian, focuses on the practical effects of Pompey’s career: the unprecedented concentration of military power, the development of personal client networks that paralleled state authority, and the creation of legal precedents later exploited by Augustus. Whether or not Pompey intended to transform the Republic, his methods established patterns that made transformation possible.

Recent scholarship has increasingly questioned whether this dichotomy captures the complexity of late republican politics. Pompey may have genuinely believed he was serving the Republic while simultaneously pursuing unprecedented personal power. The contradiction was not hypocrisy but reflected the Republic’s structural transformation under pressures of empire, class conflict, and political violence. Understanding Pompey requires acknowledging both his constitutional conservatism and his role in creating conditions that made constitutional government impossible.

Selected Sources

Ancient Sources: Caesar, Commentarii de Bello Civili; Plutarch, Lives of Pompey and Caesar; Appian, Civil Wars and Mithridatic Wars; Cassius Dio, Roman History, Books 36-42; Cicero, Letters to Atticus and Pro Lege Manilia; Lucan, Pharsalia.

Modern Scholarship: Robin Seager, Pompey the Great: A Political Biography (2nd ed., 2002); Matthias Gelzer, Pompeius (1949/1984); Peter Greenhalgh, Pompey: The Roman Alexander (1980) and Pompey: The Republican Prince (1981); John Leach, Pompey the Great (1978); Erich Gruen, The Last Generation of the Roman Republic (1974); Adrian Goldsworthy, In the Name of Rome (2003).

Specialized Studies: Philip de Souza, Piracy in the Graeco-Roman World (1999); Arthur Keaveney, Lucullus: A Life (1992); Brian McGing, The Foreign Policy of Mithridates VI Eupator, King of Pontus (1986).