Sulla’s decision to lead Roman legions against Rome marked the first clear breach of a constitutional taboo and opened the era of civil wars. How did a patrician reformer become the architect of institutional violence, and why did his “restoration” of the Republic set the stage for Pompey and Caesar?

On a tense day in 88 av. J.-C., Lucius Cornelius Sulla turned his column around. The legionaries had been marching east toward Mithridates; instead, they pivoted toward Rome. Torches flared as centurions relayed orders. The soldiers’ boots beat a rhythm that no Roman ear had yet heard within sight of the walls: a Roman army advancing on the Roman city. The taboo was ancient and absolute—armies belonged beyond the pomerium—but Sulla, affronted by the sudden transfer of his Eastern command to his rival Marius, broke it. Appian distilled the shock: “No one before Sulla led a Roman army against Rome” [Appian, Civil Wars].

That nightmarish novelty framed Sulla’s career. He triumphed in the Social War, conquered Mithridates’ forces in Greece, returned to win Rome by force in 82 av. J.-C., and assumed a constitutional dictatorship “to write laws and refound the Republic.” He then resigned power, a gesture that later apologists wielded as proof of civic virtue. Yet Sulla’s proscriptions, veteran settlements, and tribunician shackles corroded the norms he claimed to protect. This article traces the genesis of his rise, reconstructs the crisis that produced the first march on Rome, unpacks its causes, surveys the historiographical debate, and weighs Sulla’s paradoxical legacy: restoration by rupture, law by sword, precedent by fear.

Sulla’s Rise

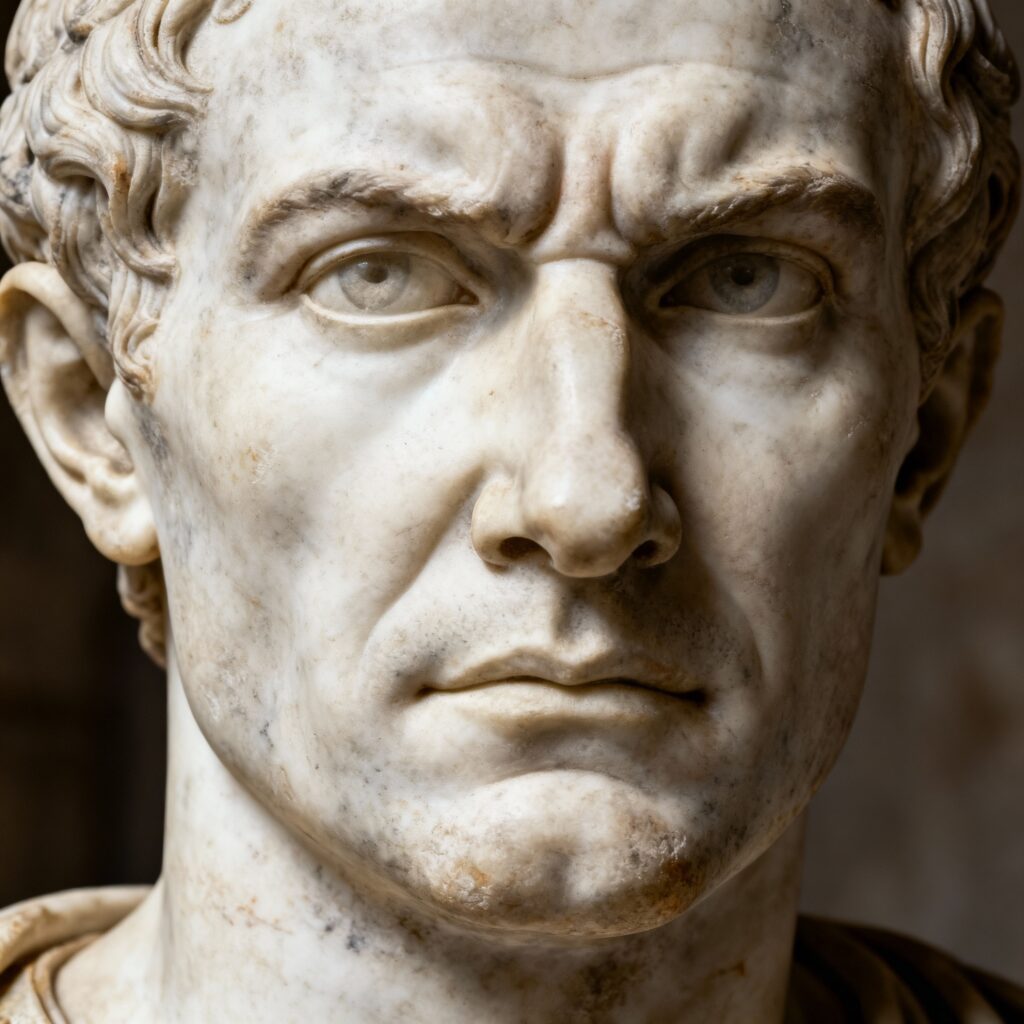

Sulla was born into a patrician but impoverished branch of the Cornelii (138 av. J.-C.). He grew up amid a Republic already fraying: the Gracchan reforms (133–121 av. J.-C.) had fused land, citizenship, and sovereignty into a volatile mix; equites had gained judicial power at senators’ expense; Italian allies pressed claims for integration; and the plebeian tribunate became a cockpit for high-stakes constitutional experimentation. In that environment, Sulla formed a style: cultivated, sardonic, theatrical. Plutarch notes his taste for the stage and his calculated coldness, the mask of a man who would later call himself “Felix,” the Lucky [Plutarch, Life of Sulla].

His ascent began under Gaius Marius during the Jugurthine War. As Marius’s quaestor, Sulla engineered the diplomatic capture of Jugurtha by winning over King Bocchus of Mauretania (105 av. J.-C.). Numidian dynastic politics delivered to Rome a bound enemy and to Sulla a silver seal-ring engraved with the scene. Plutarch preserves the image as both boast and brand [Plutarch, Life of Marius]. The partnership soon devolved into rivalry. Marius embodied the new man elevated by military success and popular support; Sulla represented a patrician sensibility that distrusted the equestrian juries and tribunes but prized the Senate’s auctoritas. Their antagonism was less biography than structure. It mapped onto Rome’s evolving power struggle between the authority of nobles and the potency of popular assemblies, between legions loyal to commanders and a state whose laws lagged behind its imperial scope.

Sulla’s martial reputation was made in the Social War (91–88 av. J.-C.), the revolt of Rome’s Italian allies seeking citizenship and full political integration. He led operations against the Samnites and other insurgents with notable energy, took strongholds, and, according to later tradition, won the rare Grass Crown for rescuing a surrounded army—the highest decoration a commander could receive from his soldiers [Pliny, Natural History]. The war’s settlement—citizenship to the Italians—remade the electorate and municipal map. It also produced battle-hardened men who measured their fortunes less by Senate decrees than by the promises of generals. Command now held not only glory but also land and loot to settle veteran claims—politics in legionary boots.

In 88 av. J.-C., Sulla and Quintus Pompeius won the consulship. The Senate assigned Sulla the coveted command against Mithridates VI of Pontus, who had swept through Asia and orchestrated a massacre of Roman residents. But domestic politics intervened. Without precedent, the tribune Publius Sulpicius Rufus used the assembly to transfer Sulla’s command to Marius. Sulla framed the act as both illegality and personal dispossession. He chose the logic of legions over the letter of law and marched on Rome. The Republic’s immunizing fictions—sacred boundaries, gradualist norms, soft concessions—collapsed into the noise of iron-shod sandals.

From First March to Dictatorship

After he seized Rome in 88 av. J.-C., Sulla annulled Sulpicius’s acts, reaffirmed his command, and pushed east, leaving the city to an uneasy Marian-Cinnan coalition that would soon reclaim it. Sulla’s Eastern campaign showcased his strengths: siegecraft, ruthlessness, political bargaining. He besieged Athens, held by Mithridates’ general Archelaus, and took the city after famine and street fighting (86 av. J.-C.). Appian records the sack’s savagery; Plutarch laments blood shed in the shadow of the Academy. Sulla crushed Mithridatic forces at Chaeronea and Orchomenus (86–85 av. J.-C.), restoring Rome’s prestige in Greece.

Yet he fought under a cloud: a hostile regime in Rome had declared him an enemy. He supplied his army by exactions, cut down sacred groves for siege works, and treated Greek poleis as under occupation. He also practiced realpolitik. At Dardanus (85 av. J.-C.), he made peace with Mithridates, exacting indemnities and surrender of conquests but leaving the king on his throne. The settlement alienated Marian commanders still fighting in Asia, notably the consul Fimbria, whom Sulla outmaneuvered. He moved west with a battle-hardened army and a ledger of unpaid debts—in coin and vendetta.

Meanwhile, in 87 av. J.-C., Marius and Cinna had marched on Rome, purging enemies and rewriting laws. Marius died soon after his unprecedented seventh consulship (86 av. J.-C.), but the Cinnan regime held the city until Sulla returned. Italy fractured. Sulla’s arrival in 83 av. J.-C. ignited the Second Civil War. Young nobles flocked to his standards, including a rising Pompeius (later called Pompey), who raised his own forces in Picenum. In 82 av. J.-C., Rome’s fate turned on brutal set-piece battles. At the Colline Gate, outside Rome’s northern walls, Sulla’s army met a coalition of Samnite and Marian forces. The fighting was close, vicious, personal. Plutarch describes Sulla rallying his right where collapse seemed imminent, a general who made nerve a doctrine [Plutarch, Life of Sulla].

Victory at the Colline Gate opened the city and the country. What followed was not merely a purge but an innovation of terror with a ledger. Sulla introduced proscriptions—official lists of the condemned whose properties were confiscated, names posted, and persons declared outlaws. The legalistic gloss framed mass political murder as due process. Appian, prone to dramatic arithmetic, gives tall figures; modern scholars caution about precision but concur on scale and intent. The proscriptions shattered families, enriched followers, and seeded fear. Cicero remembered the period with trembling admiration and cautious horror, praising Sulla’s talents while recoiling from his violence [Cicero, Letters].

Amid the blood, Sulla recast the constitution. The Senate named him dictator legibus scribundis et rei publicae constituendae (82/81 av. J.-C.), a dictatorship “to write laws and refound the Republic,” open-ended in duration and scope. He expanded the Senate from roughly 300 to about 600, replenishing its ranks with his supporters. He curtailed the tribunate: tribunes lost the power to propose laws unaided, and ex-tribunes were barred from further magistracies—a calculated deterrent. Juries returned from equestrian to senatorial control, reversing a Gracchan pillar. He formalized criminal courts (quaestiones perpetuae), regularized provincial commands for consuls and praetors, and adjusted the cursus honorum with age minima. He settled veterans on confiscated lands across Italy, a pattern that yoked social engineering to political loyalty. He abolished the grain dole established by Gaius Gracchus, striking at popular largesse.

Then he stepped down. In 79 av. J.-C., Sulla resigned the dictatorship and retired to Campania, living with ostentation and disconcerting ease under the nickname Felix. Plutarch cites a sardonic epitaph: “No friend did me a kindness and I repaid him more; no enemy did me a wrong and I repaid him more” [Plutarch, Life of Sulla]. He died in 78 av. J.-C., leaving behind a Republic both restored and ruined—law re-inscribed over wounds that would not scar.

Why the March Happened

Sulla’s march on Rome cannot be reduced to personality, however magnetic the portrait of a patrician ironist with a taste for theater and vengeance. The causes were structural, contingent, and cumulative.

- The militarization of politics. The Social War transformed Italy into a recruiting basin of newly enfranchised communities, tied to commanders by shared risk and promised reward. Legions began to see the state through the lens of their general’s fortunes. Sulla stepped into a pattern already set by Marius’s Marian legions, but he advanced it: he made the army the instrument of constitutional revision.

- The crisis of command. Eastern command against Mithridates promised prestige, plunder, and the strategic reset of Roman power in Asia. The assembly’s transfer of that command from Sulla to Marius was not merely a professional slight; it signaled a constitutional practice in which any office could be unstitched by popular vote at a moment of high stakes. The general’s calculus shifted. If law can rescind command, and command is the basis of victory and survival, then army decides law—a deadly inversion.

- The judicial revolution and elite fractures. Since 122 av. J.-C., equestrian juries in the extortion court had checked senatorial governors and rebalanced power. Senators bridled. Tribune-led legislation turned the plebs into an arena where rival noble factions hammered policy into weapons. Sulla’s reforms targeted these points: juries back to senators, tribunate shackled, magistracy cursus locked. He aimed to freeze elite competition by formal rules that favored senatorial collegiality and experience over tribune-led shocks.

- Italian citizenship and municipal reordering. Enfranchisement multiplied the citizen body and transformed the balloting geography. The Marian-Cinnan camp cultivated this new electorate; Sulla sought to channel it through curial governance and municipal elites that answered to a reinvigorated Senate. His veteran settlements, while coercive, also planted new civic nuclei tied to senatorial authority and his personal network.

- The economic stakes of empire. Mithridates’ rampage across Asia and the massacre of Roman residents exposed the vulnerabilities of Italy’s creditor class and the revenue streams of publicani (tax contractors). Command in the East meant the power to renegotiate Asia’s future, to levy indemnities, and to distribute patronage. The financial dimension sharpened the political fight over who led the war.

- Precedents of violence. Political bloodshed had erupted before Sulla: the killings of the Gracchi (133, 121 av. J.-C.), Saturninus’s suppression (100 av. J.-C.), and street gangs under Sulpicius and later Clodius. Yet marching legions into Rome crossed a sacred line. Sulla did not invent political violence; he institutionalized it at the center with the appearance of legality. He wrote lists. He fused sword and statute.

Individually, these factors strained the system; together, they cracked it. Sulla’s march responded to a constitutional paradox: as popular sovereignty broadened, its instruments could be captured by narrow coalitions. Sulla gambled that a shock—military intervention followed by juridical entrenchment—could restore equilibrium. The gamble succeeded in coercing a settlement; it failed in curing the disease. The very means of restoration taught future strongmen where the levers were and how to pull them harder.

Debate and Controversies

Ancient sources shape Sulla through lenses of moral judgment and political utility. Modern historians, triangulating those voices with epigraphy and institutional analysis, debate five persistent themes.

- Was Sulla “first” to march on Rome? Appian’s formulation—Sulla as the first to lead an army on Rome—captures a genuine novelty: legions under their commander crossing the city’s threshold to impose a political outcome. Earlier violence was senatorial or mob-based; Marius and Cinna marched on the city in 87 av. J.-C., but Sulla’s 88 av. J.-C. precedent was conceptually disruptive: it fused command with constitutional veto. Some caution that in 100 av. J.-C. Marius deployed troops to suppress Saturninus inside Rome, but this was done as a consular duty within a senatorial emergency decree. Sulla’s act was self-authorization against an assembly’s decision, a qualitative break.

- Restorer or reactionary? Sulla’s own title—dictator legibus scribundis et rei publicae constituendae—invite readings. He enlarged the Senate, stabilized the cursus, and multiplied courts; these look like constructive reforms. Yet he crippled the tribunate and packed the Senate with clients. Scholars debate intent. Was Sulla building a more regular, law-bound Republic or erecting safeguards for a narrow oligarchy? Modern analysis emphasizes the structural logic of his reforms but notes their short half-life: within a decade, Pompey and Crassus restored tribunician powers (70 av. J.-C.), suggesting that Sulla’s settlement lacked political legitimacy beyond fear.

- The scale and function of proscriptions. Appian and Plutarch dramatize numbers; Cicero’s letters personalize the losses. Debate persists over figures and motives. Some stress targeted political cleansing fused to fiscal extraction for veterans and supporters—a war economy of confiscation. Others underline the performative, deterrent effect: lists as spectacle, the city taught to read death on walls. A consensus holds that proscriptions institutionalized civil war as policy, creating a reusable script later invoked by the Second Triumvirate (43 av. J.-C.).

- Sulla’s character and “luck.” Plutarch dwells on the theatrical Sulla, the “Felix” who believed fortune favored him. Is this moralizing hindsight? Personal traits mattered—coolness in crisis, vicious memory, taste for display—but modern accounts tend to integrate character into structural analysis: Sulla was the right kind of man to operationalize a system’s vulnerabilities. His calculated resignation reads less as Cincinnatus and more as a chess player exiting after resetting the board with rooks in his pocket.

- The Social War’s weight. Some interpretations underplay the Social War as prelude; others place it at the center. The war reordered Italy, forged Sulla’s command reputation, and turned citizenship from ideology into administrative reality. It also radicalized politics: Italians enfranchised by war had expectations the Senate could not meet without empowering tribunes; commanders saw that military success conferred a political currency stronger than precedent. The Social War appears not as background but as generative crucible.

Ancient voices diverge. Plutarch crafts exempla; Appian builds tragedy; Sallust (in fragments) hints at moral decay in the nobility; Velleius Paterculus admires the military organizer. Modern historians—Arthur Keaveney on Sulla’s political logic, H. H. Scullard on the late Republic’s fault lines, Andrew Lintott on constitutional form, Elizabeth Rawson on aristocratic culture, Erich Gruen on resilience—variously place Sulla as hinge or hammer. Yet a quiet convergence emerges: Sulla is not an aberration but an accelerator. He turned latent instabilities into operating procedures.

Consequences and Legacies

Sulla’s settlement outlived him—and it did not. The Senate absorbed new members and oversaw a more elaborated court system. Some provincial arrangements and legal codifications persisted. But the heart of the Sullan package—tribunician shackles and senatorial jury monopoly—was undone in 70 av. J.-C. under Pompey and Crassus, who found it expedient to court popular goodwill. The reversal tarnished Sulla’s claim to have effected a consensual restoration. If the settlement had felt legitimate, it would not have needed so much blood to hold; without the sword, it dissolved.

More durable was the lesson of means. Pompey learned that an ambitious general could raise private forces, win extraordinary commands, and demand office. His Spanish command against Sertorius and the sweeping lex Gabinia against pirates (67 av. J.-C.) habituated Rome to emergency delegations. Caesar, in turn, absorbed the cardinal principle of Sulla’s march: if institutional survival requires impunity, one must bring the army home. Crossing the Rubicon (49 av. J.-C.) was Sulla’s first march stripped of its restorationist rhetoric and draped in a new narrative of clemency. Even Caesar’s proscriptions—largely eschewed in his first consolidation—returned with a vengeance under the Second Triumvirate (43 av. J.-C.), a grim homage to Sulla’s list politics.

At the social level, Sulla’s veteran colonies reconfigured Italy’s landholding and municipal politics. Settlements bred local aristocracies loyal to the Sullan network but also sowed resentment among dispossessed communities. The memory of confiscation lingered. Legal reforms—especially the crystallization of permanent courts—shaped Roman criminal procedure well into the late Republic. The Senate’s numerical expansion normalized a broader elite, even after Sullan clients faded.

In the ideology of power, Sulla’s dictatorship rebranded emergency authority. The old six-month dictatorship had withered since the Second Punic War. Sulla revived the title with a new mandate and indefinite term. Later rulers would avoid the word but adapt the substance. Augustus refined the lesson: exercise extraordinary power without the stain of the name. Sulla taught two paths—naked terror and formal reconstitution—whose combination laid the grammar of Roman authoritarianism.

Outside Rome, Greek cities remembered Sulla as a conqueror and plunderer; Asia remembered indemnities and selective leniency. Mithridates survived to fight again. Sulla’s peace was kinetic, tactical, and personal. It secured Rome’s short-term position but did not resolve the strategic question of how a city-state governs an empire without generals outrunning laws.

Conclusion Synthesis

Sulla stands at the pivot where a civic creed yielded to a military grammar. He did not invent Rome’s crisis, nor did he end it. He gave it a method: march, purge, legislate, resign. Each verb answered a real problem. The assemblies had undercut strategic command; he marched. The political class was at war with itself; he purged. The constitutional order was incoherent; he legislated. The tyrant’s stain was indelible; he resigned. Yet taken together, these acts widened the channel through which future power would flow. The Republic Sulla claimed to restore was not the flexible polity of the middle second century, capable of co-opting dissent and reforming itself under pressure. It was a more brittle architecture, momentarily stabilized by fear and procedure but bound to collapse under the weight of the very tools he normalized.

Historians may continue to argue whether Sulla was restorer, reactionary, or revolutionary in conservative dress. The record—Plutarch’s vivid set pieces, Appian’s tragic cadence, Cicero’s nervy respect—supports all three portraits at different angles. The more useful frame is structural. Sulla’s career reveals what happens when legal order depends on men whose ambitions the law cannot contain and whose soldiers the city cannot ignore. He remains, in that sense, Rome’s most paradoxical teacher: the dictator who proved that constitutions break not when they are violated, but when they require violation to function.

Landmarks

- 138 av. J.-C.: Birth of Lucius Cornelius Sulla in a patrician but poor branch of the Cornelii.

- 105 av. J.-C.: Diplomatic capture of Jugurtha; rivalry with Marius intensifies.

- 91–88 av. J.-C.: Social War; Sulla earns major victories and lasting military reputation.

- 88 av. J.-C.: Consulship; assembly transfers Eastern command to Marius; first march on Rome.

- 86–85 av. J.-C.: Siege of Athens; victories at Chaeronea and Orchomenus; peace at Dardanus.

- 83–82 av. J.-C.: Second Civil War in Italy; victory at the Colline Gate.

- 82/81 av. J.-C.: Dictatorship to “refound the Republic”; proscriptions; constitutional reforms.

- 79 av. J.-C.: Voluntary resignation of the dictatorship; retirement to Campania.

- 78 av. J.-C.: Death; the Sullan settlement begins to fray.

Debate

Did Sulla “restore” the Republic or rewire it for collapse? Advocates of the restoration thesis cite expanded courts, a regularized cursus honorum, and Sulla’s resignation. Critics stress tribunician shackles, packed juries, and legalized terror. A middle view sees design and damage together: Sulla imposed rules that solved immediate elite dysfunctions but at the cost of teaching Rome how to use armies to settle politics. The rapid repeal of key reforms (70 av. J.-C.) undermines claims of stable restoration. Yet the codification of criminal courts and a larger Senate endured. The question is less binary than temporal: Sulla restored a Republic that could not survive the lessons of its restoration.

Credits and Sources

Primary sources: Plutarch, “Life of Sulla” and “Life of Marius”; Appian, “Civil Wars”; Sallust, fragments of “Histories”; Cicero, speeches and letters; Velleius Paterculus, “Roman History”; Livy, Periochae; Pliny the Elder, “Natural History.” Epigraphic and legal evidence: Cornelian laws, senatus consulta, municipal inscriptions from Italy and Asia. Modern works: Arthur Keaveney, “Sulla: The Last Republican”; H. H. Scullard, “From the Gracchi to Nero”; Andrew Lintott, “The Constitution of the Roman Republic”; Elizabeth Rawson, “Roman Culture and Society”; Erich Gruen, “The Last Generation of the Roman Republic”; Adrian Goldsworthy, “In the Name of Rome.”