The Dagger That Shaped Democracy

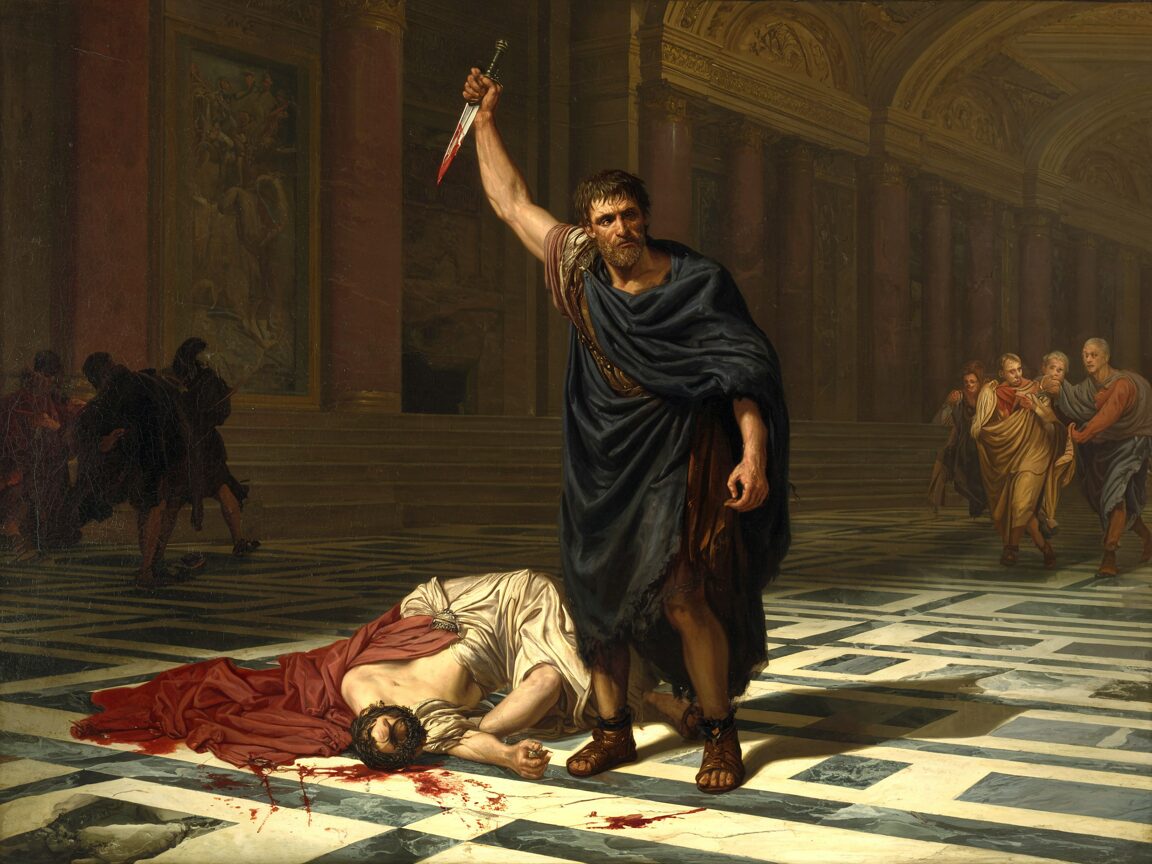

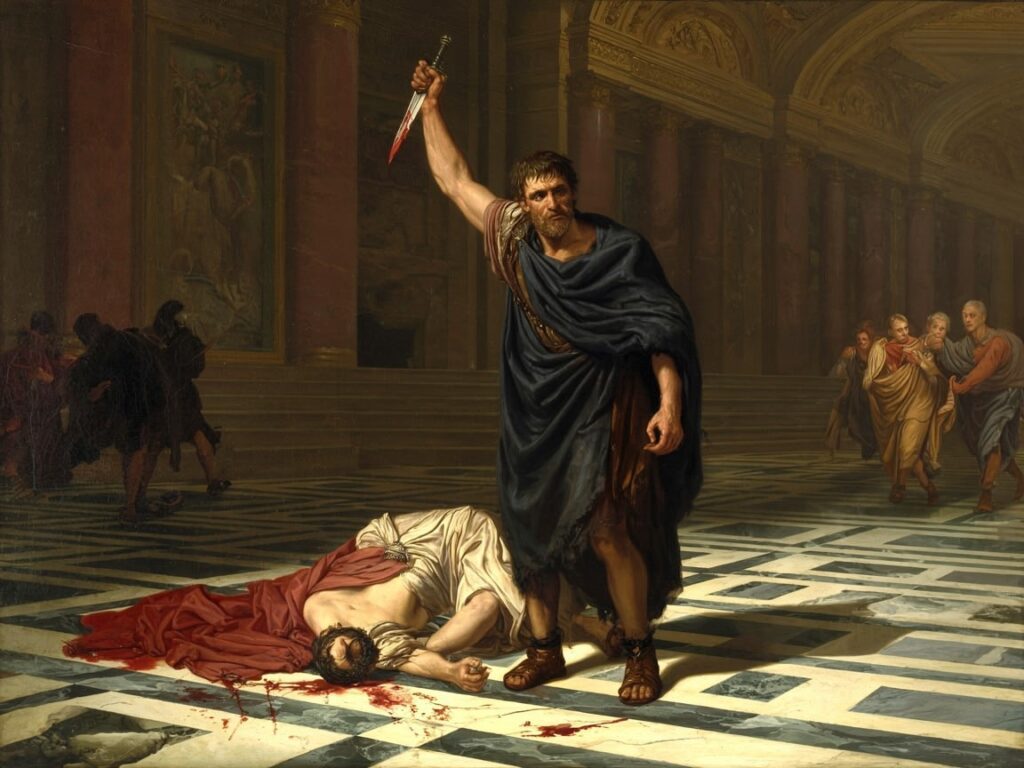

Blood dripped from the Senate floor as twenty-three wounds marked the fallen body of Rome’s most powerful man. Standing above the lifeless form of Julius Caesar, his trusted friend Marcus Junius Brutus raised a bloodied dagger toward the ceiling of the Theatre of Pompey. “People of Rome,” he declared to the panicked onlookers, “we are free again.” In that moment on the Ides of March in 44 BCE, Brutus wasn’t merely participating in an assassination—he was making a philosophical statement that would echo through millennia of political thought.

The brutal killing of Caesar represents perhaps history’s most famous political murder, but beneath the violence lies a profound ethical dilemma that continues to haunt democratic societies: When does loyalty to democratic principles supersede personal loyalty? When is revolution justified? And can democracy sometimes require terrible actions to preserve itself?

These questions didn’t begin with Brutus, but his actions crystallized them in a way that would forever change how humanity views the relationship between power, leadership, and the governed. The repercussions of his decision continue to influence democratic thinking today, making the “Brutus Protocol”—the moral justification for opposing tyranny—a cornerstone of Western political philosophy.

To understand the significance of Brutus’ choice and its lasting impact on democratic thought, we must first transport ourselves to the turbulent final days of the Roman Republic, where political ideals clashed with the reality of power’s corrupting influence.

Rome Before Caesar: Republic in Name, Dysfunction in Practice

The Rome that Brutus inherited was a republic in crisis. Founded nearly five centuries earlier after the overthrow of the monarchy, Rome had developed sophisticated democratic mechanisms: elected officials, checks on power, and the concept that no single person should rule indefinitely. The Senate, composed of aristocratic elders, worked alongside elected magistrates to govern, while popular assemblies gave ordinary citizens some voice in government. This system had guided Rome from a small Italian settlement to the Mediterranean’s dominant power.

Yet by the first century BCE, this republican system was buckling under its own success. Rome’s expansion had created vast wealth disparities, with aristocratic families controlling enormous resources while returning soldiers struggled to maintain their small farms. Political offices that were once honors became prizes in an increasingly corrupt system. Violence had become a standard political tool, with street gangs enforcing political will and assassinations removing opponents.

The decades before Caesar’s rise had seen a parade of powerful men attempt to address these problems through increasingly authoritarian means. Generals like Marius and Sulla had marched armies on Rome itself. Political reformers like the Gracchi brothers were murdered for proposing land redistribution. Civil wars erupted repeatedly. The republican institutions remained, but their functioning had become deeply compromised.

Into this dysfunction stepped Julius Caesar—brilliant, charismatic, and enormously ambitious. After successful military campaigns in Gaul, Caesar returned to Italy, crossing the Rubicon river with his loyal legions in 49 BCE—an illegal act that triggered civil war. After defeating his opponents, Caesar accumulated unprecedented powers: dictator for life, control of the military, and effective veto over the Senate. While he implemented popular reforms addressing debt and poverty, his concentration of power struck at the heart of republican principles.

For traditionalists like Brutus, Caesar represented not just political opposition but an existential threat to the republic itself. The Rome before Caesar was deeply flawed, but it maintained the principles of shared governance. Caesar’s Rome was moving rapidly toward one-man rule—efficient perhaps, but fundamentally at odds with the republican ideals that had defined Roman identity for centuries.

The Man Behind the Dagger: Brutus’ Philosophical Crucible

What makes the story of Caesar’s assassination so compelling is not just the dramatic elements—betrayal, violence, political intrigue—but the complex character of the principal assassin. Marcus Junius Brutus was no ordinary political opponent. Born to the Roman elite and raised with strict adherence to Stoic philosophy, Brutus embodied republican virtue in many Romans’ eyes. His lineage supposedly traced back to Lucius Junius Brutus, who had helped overthrow Rome’s last king and establish the republic.

The relationship between Brutus and Caesar adds another layer of moral complexity. Caesar had shown particular favor to Brutus, possibly believing him to be his illegitimate son from an affair with Brutus’ mother Servilia. During their earlier civil war, Brutus had actually supported Caesar’s opponent Pompey, yet Caesar ordered his troops to capture Brutus alive if possible. After Pompey’s defeat, Caesar welcomed Brutus back, granting him governorship of Gaul and later a praetorship in Rome—prestigious positions that demonstrated Caesar’s trust.

This personal connection makes Brutus’ decision all the more significant. He chose abstract republican principles over personal loyalty and advancement. His philosophical background, particularly his adherence to Stoicism with its emphasis on virtue and duty, provided the framework for this difficult moral choice. In Brutus’ worldview, the long-term preservation of liberty required sacrificing not only his relationship with Caesar but potentially his own moral purity.

Contemporary accounts suggest Brutus agonized over the decision. Plutarch describes how anonymous messages appeared at Brutus’ home, bearing phrases like “You are not a true Brutus” and “Your ancestors would not have wanted kings.” These appeals to his family legacy and republican duty apparently weighed heavily on his conscience. Meanwhile, the conspirator Cassius worked to convince Brutus that Caesar intended to crown himself king—the ultimate Roman political taboo.

The philosophical justification Brutus eventually embraced was tyrannicide—the idea that killing a tyrant is not murder but a necessary act to preserve freedom. This concept wasn’t new; Greek philosophers had debated it for centuries. But Brutus’ application of this principle in the most visible political arena of the ancient world transformed it from abstract theory to political precedent. In choosing to act against Caesar, Brutus was asserting that republican principles transcended both personal relationships and legal frameworks that had been corrupted by power.

The Bridge to Chaos: Immediate Aftermath and Unintended Consequences

The conspirators’ hope for an immediate restoration of republican governance proved dramatically misplaced. Rather than rallying to support the assassination, many Romans reacted with shock and anger. The funeral oration delivered by Mark Antony—immortalized by Shakespeare’s “Friends, Romans, countrymen” speech—masterfully channeled public sentiment against the assassins. Within days, Brutus and his co-conspirators fled Rome for their safety as mobs searched for them.

What followed was precisely the chaos the assassination was meant to prevent. Rome descended into another devastating civil war as Caesar’s adopted heir Octavian (later Augustus) allied with Mark Antony to hunt down the conspirators. Brutus and Cassius raised armies in the eastern provinces, leading to a decisive battle at Philippi in 42 BCE. Facing defeat, Brutus committed suicide, reportedly declaring before his death, “Caesar, now I can die more freely than I lived.”

The ultimate political outcome would have horrified Brutus. After defeating the conspirators, Octavian and Antony temporarily shared power before turning against each other. Octavian’s eventual victory effectively ended the republic. While maintaining a facade of republican institutions, Octavian—now styled as Augustus—created the Principate, a system where real power rested with the emperor. The republic that Brutus had killed to preserve was replaced by the very thing he feared most: monarchy in all but name.

This immediate failure has led many historians to view the assassination as a catastrophic miscalculation. The conspirators understood what they were against—Caesar’s concentration of power—but had no viable plan for what would replace it. They fatally underestimated both Caesar’s popularity among ordinary Romans and the degree to which republican institutions had already decayed. The assassination removed a man but couldn’t address the structural problems that had allowed his rise.

Yet historical judgment must consider more than immediate outcomes. The question remains whether the Roman Republic was already beyond saving by 44 BCE. Some historians argue that the transition to imperial rule was inevitable given Rome’s size and complexity. If so, Brutus’ actions might be seen not as a tactical error but as a powerful symbolic stand—establishing an ethical position that would influence political thought long after Rome itself had fallen.

Rome After Brutus: The Paradoxical Legacy

The immediate political aftermath of Caesar’s assassination may have been the opposite of what Brutus intended, but its long-term intellectual and philosophical impact proved far more significant. Though the Republic fell, the idea that tyranny should be resisted—even at great personal cost—entered the Western political tradition as a foundational principle.

Augustus and his successors, recognizing the power of this idea, walked a careful line. While holding near-absolute power, they maintained republican facades. Emperors styled themselves as “First Citizen” rather than king, preserved the Senate as a deliberative body (though with diminished powers), and justified their authority through claims of restoring order rather than overturning tradition. This demonstrates how even in defeat, the republican ideals Brutus championed imposed constraints on how power could be legitimately exercised.

Throughout the subsequent centuries of Roman imperial rule, the memory of Brutus remained ambivalent. Official histories commissioned by emperors naturally portrayed him as a villain who brought chaos through his actions. Yet among philosophical circles, particularly Stoics, Brutus was often quietly revered as someone who sacrificed everything for principle. This underground admiration kept republican ideals alive even during the height of imperial power.

When republican and democratic thought reemerged during the Renaissance, Brutus became a central figure in political discourse. Machiavelli, in his Discourses on Livy, examined the assassination as a case study in republican governance. Renaissance artists depicted the scene, using it to reflect on questions of political legitimacy in their own time. For humanist thinkers rediscovering classical texts, Brutus represented the ancient republican tradition they hoped to revive.

By the time of the Enlightenment and the great democratic revolutions of the 18th century, Brutus had been fully rehabilitated as a republican hero. The American revolutionaries explicitly compared their struggle against King George III to the ancient resistance against tyranny. The French revolutionaries went further—during the Reign of Terror, many justified execution of the king by citing classical precedents, with Brutus foremost among them.

This historical transformation reveals the paradox at the heart of Brutus’ legacy. His immediate political failure ultimately contributed to a more profound ideological success. By creating such a dramatic historical example, Brutus helped ensure that even during centuries when democratic governance disappeared from practice, it remained alive as a philosophical possibility—ready to be reclaimed when historical circumstances allowed.

The Brutus Protocol in Modern Democracy

The questions Brutus confronted continue to resonate in modern democratic societies: When is resistance to authority justified? What limits should constrain executive power? How can democratic systems protect themselves from internal threats? These issues, first crystallized in Brutus’ dilemma, have become encoded in modern constitutional arrangements.

Consider how modern democracies have institutionalized resistance to potential tyranny. The American system’s separation of powers directly addresses the concern that motivated Brutus—preventing any individual from accumulating Caesar-like authority. Constitutional provisions for impeachment create legal pathways to remove leaders who abuse power, theoretically making the “Brutus solution” unnecessary. Independent judiciaries, term limits, and protected rights all represent systemic responses to the problem Brutus addressed through individual action.

When modern politicians invoke defending democracy against authoritarianism, they are drawing on a tradition that traces directly back to the Ides of March. When constitutional scholars debate the limits of executive power, they are participating in a conversation Brutus began with his dagger. The assassination itself may be universally condemned as a method in modern politics, but the principle behind it—that democracy sometimes requires difficult actions to preserve itself—remains embedded in democratic theory.

Even the language we use to discuss democracy reflects this legacy. We speak of “checks and balances,” “tyranny of the majority,” and “constitutional crises”—concepts that would have been immediately recognizable to Brutus and his contemporaries. Our modern democratic vocabulary was forged in the crucible of Rome’s transition from republic to empire.

This historical connection was particularly evident during the 20th century’s struggles against totalitarianism. The German military officers who attempted to assassinate Hitler in 1944 explicitly compared themselves to the Roman conspirators. Cold War rhetoric framing democracy’s struggle against communism drew on republican Roman imagery. More recently, concerns about democratic backsliding in various countries have prompted renewed interest in how democracies fail—with the fall of the Roman Republic serving as the archetypal case study.

The Brutus Protocol thus represents more than a historical curiosity—it continues to function as an active principle in democratic governance. When we debate whether extraordinary measures are justified to protect democratic institutions, we are engaging with the same fundamental question Brutus faced: How far should one go to preserve a system of government against threats that arise within it?

The Moral Complexity of Democratic Defense

The lasting significance of Brutus’ decision lies not in providing a simple answer to questions of democratic defense, but in highlighting their inherent moral complexity. His actions force us to confront uncomfortable paradoxes at the heart of democratic governance.

The first paradox involves means and ends. Brutus used undemocratic means (political violence) to supposedly preserve democratic institutions. This contradiction continues to trouble democratic theorists. When democratic systems face internal threats, can undemocratic methods ever be justified in their defense? Modern democracies face this dilemma when considering whether to ban anti-democratic parties or restrict certain types of speech that threaten democratic stability.

A second paradox concerns legitimacy. The conspirators acted without popular mandate, believing they knew better than the Roman people what was in the republic’s interest. This tension between elite guardianship and popular sovereignty remains unresolved in modern democracy. When elected leaders appear to threaten democratic norms, who has the authority to intervene? Courts? Legislatures? The military? Citizens themselves? Each potential answer raises problems of democratic legitimacy.

The third paradox involves the relationship between principles and personalities. Brutus opposed Caesar’s concentration of power on principle, yet the conspiracy focused on eliminating the man rather than reforming the system. Modern democracies similarly struggle with distinguishing between opposing problematic leaders and addressing the conditions that allow their rise. The personalization of political conflict often obscures deeper structural issues.

These paradoxes make the Brutus Protocol more than a historical curiosity—it’s a lens through which we can examine our own democratic commitments. The assassination forces us to consider what democracy actually means to us. Is it primarily a set of procedures and institutions? A collection of rights and protections? Or a deeper ethical commitment to shared governance that sometimes transcends specific laws?

Perhaps most importantly, Brutus’ example reminds us that democracy requires moral courage. While his specific actions belong to another time, his willingness to sacrifice personal advantage for principle remains relevant. Modern democratic citizenship rarely demands such dramatic choices, but it still requires putting collective interests above personal gain—a message as challenging today as it was on the Ides of March.

Conclusion: The Eternal Ides of March

Over two thousand years after Brutus raised his blood-stained dagger in the Theatre of Pompey, his decision continues to haunt our political imagination. His failure to save the Republic paradoxically ensured that republican ideals would survive, providing inspiration for democratic movements across centuries and continents.

The Brutus Protocol—the principle that tyranny must be actively opposed to preserve freedom—has evolved from justifying assassination to supporting constitutional constraints, from a desperate last resort to a foundational element of democratic design. Modern democracies have institutionalized what Brutus attempted through individual action, creating systems where power is checked not by daggers but by laws, independent institutions, and citizen vigilance.

Yet the fundamental ethical dilemma Brutus faced remains with us. Democratic societies still struggle to balance security with liberty, stability with accountability, and personal loyalty with civic duty. When democratic norms are threatened, citizens still face choices about when and how to resist. The specifics change, but the essential question persists: What are we willing to sacrifice to preserve the principle that people should govern themselves?

The true legacy of the Ides of March lies not in providing easy answers to these questions, but in forcing us to acknowledge their complexity. By contemplating Brutus’ choice—with all its moral ambiguity and unintended consequences—we gain deeper insight into our own democratic commitments. We are reminded that democracy is not merely a system of government but an ongoing ethical project requiring constant vigilance and occasional courage.

In this sense, every democracy lives perpetually in the shadow of the Ides of March. The daggers may be metaphorical now, but the responsibility to defend democratic governance against its internal threats remains as urgent as it was on that fateful day in 44 BCE. Brutus’ decision, for better or worse, changed the course of democracy forever—not by saving the Roman Republic, but by ensuring that its ideals would endure long after its institutions had crumbled.