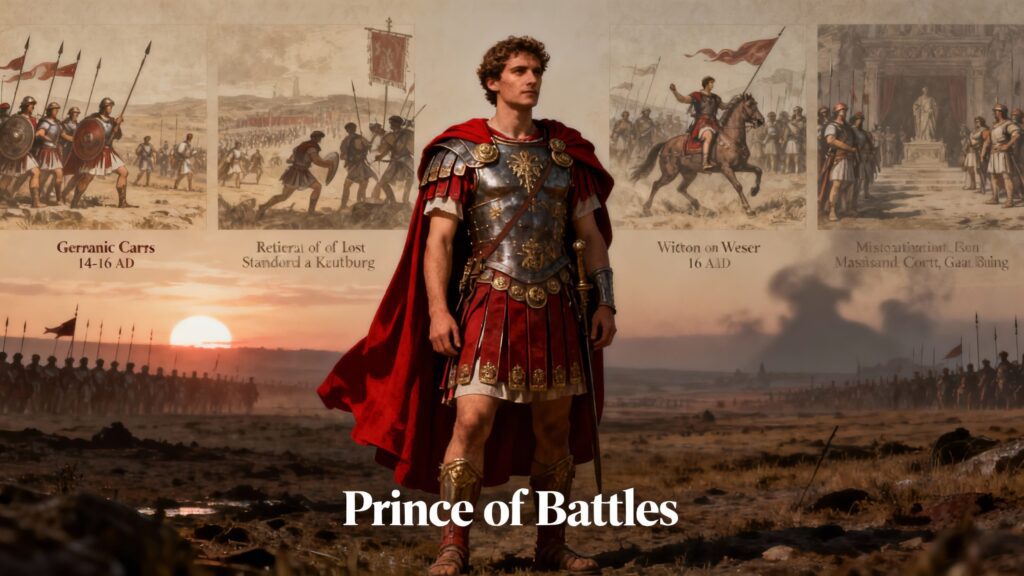

Germanicus stands out as the brilliant Julio‑Claudian heir whose battlefield genius and immense popularity seemed to guarantee a future reign, only for a sudden death in the East to turn promise into tragedy, reshaping Roman politics and memory for generations. His German campaigns avenged the Varus disaster, recovered lost legionary standards, and culminated in a famed victory on the Weser before a recall, an Eastern command, and a death widely suspected—then and later—to have involved poisoning that was never proven.

Why it is tragic

Germanicus was adopted by Tiberius in 4 CE, rose rapidly through Rome’s highest magistracies, and, after three triumphal campaigning seasons, returned to celebrate a spectacular triumph in 17 CE, positioning him as the empire’s most beloved and plausible next ruler. Instead of consolidation at Rome, he was dispatched to the East with extraordinary powers, became embroiled in a feud with the Syrian governor Calpurnius Piso, and then died at Antioch in 19 CE amid allegations of poisoning that a Senate trial could not resolve, leaving suspicion to shadow Tiberius and the regime. The grief that followed, the posthumous honors, and the political aftershocks underscored how abruptly Rome had lost a commander many contemporaries likened to an Alexander cut off in youth.

Designated heir of Tiberius

Augustus arranged in 4 CE for Tiberius to adopt Germanicus, thereby placing him next in the line of succession through a carefully engineered Julio‑Claudian compromise that also bonded him by marriage to Augustus’s granddaughter, Agrippina the Elder. This settlement made Germanicus the dynastic bridge between the Claudian line of Tiberius and the Julian heritage of Augustus, amplifying his status as heir apparent in the public eye and Senate. His children would include the future emperor Caligula and Agrippina the Younger, mother of Nero, while his brother would become the emperor Claudius, illustrating the dynastic centrality that heightened the stakes of his early death.

After Varus: mission and motive

Following Augustus’s death in 14 CE, mutinies erupted among Rhine legions that Germanicus suppressed with personal authority and adroit concessions, after which he immediately carried war across the Rhine to punish Arminius and avenge Varus. With eight legions—about a third of Rome’s army—he combined land and river operations to overcome terrain and logistics, using fleets to multiply reach and surprise in northern Germania’s forests and swamps. Tacitus frames these campaigns explicitly as vengeance for Teutoburg rather than an annexation bid, a rationale that colored both their ferocity and their political reception at Rome.

Germania, campaign of 14 CE

In the immediate wake of the legions’ revolt, Germanicus stabilized the Rhine armies and led a punitive strike against the Marsi, devastating settlements and reasserting Roman dominance on the frontier as a prelude to deeper operations. This rapid action re‑cemented discipline and prestige, setting the tone for the more ambitious expeditions of 15 and 16 CE. The political message matched the military one: Rome could both regulate its own troops and punish external foes swiftly after the Varus shock.

Germania, campaign of 15 CE

In spring 15 CE Germanicus struck the Chatti, sacked their capital Mattium, and then advanced through Cheruscan territory to recover prisoners and high‑value captives—including Thusnelda, Arminius’s wife—while ritually honoring Roman dead at Teutoburg before resuming the march. In the Bructeri country, Lucius Stertinius recovered the lost eagle of the XIX Legion, a potent symbol that signaled moral and political vindication after the humiliation of 9 CE. Though ambushed amid the bogs of the pontes longi, Germanicus extracted his army without decisive loss, underscoring his operational resilience under Germanic harassment.

Germania, campaign of 16 CE

For the climactic 16 CE season, Germanicus built a fleet of roughly a thousand ships to shift the theater by sea and river, projecting legions deep into the interior and sparing the horses in anticipation of pitched battle on terms favorable to Rome. He then forced Arminius into open combat at Idistaviso on the Weser, routing the Germanic coalition in a daylong slaughter and following up with another victory at the Angrivarian Wall when the enemy counterattacked in fury. Although a storm wrecked many transports during the maritime withdrawal, the campaign’s tactical results were decisive, and Germanicus’s forces erected trophies proclaiming the subjugation of tribes between Rhine and Elbe before a politically charged recall ended the advance.

Vengeance for Varus

Each year’s operations were framed by Tacitus and later tradition as a deliberate reckoning for Teutoburg, aimed at punishing Arminius and humiliating his allies rather than adding new provinces east of the Rhine. The long ceremonial pause to bury Roman bones at the battle site, followed by controlled fury against nearby tribes, dramatized both the memory politics and the moral purpose assigned to the war by Germanicus and his admirers. Even Rome’s trophies and triumph would stress recovered honor—standards, captives, and battlefield victories—over territorial annexation, aligning strategy to symbolism.

Recovering the lost standards

Germanicus’s forces recovered two of the three eagles lost in 9 CE, including the standard of the XIX Legion taken from the Bructeri, with later campaigning under Claudius reclaiming the final eagle to complete the restoration of Rome’s honor. The XIX’s eagle was retrieved in 15 CE amid Bructeri equipment, and additional recoveries followed during or soon after Germanicus’s punitive operations across the region. The standards were ultimately housed in the Temple of Mars Ultor, knitting Germanicus’s achievements into the Augustan narrative of vengeance and restitution that the monument embodied.

Victory on the Weser (16 CE)

The Battle of Idistaviso—also called the Battle of the Weser River—forced Arminius into the open, where Roman heavy infantry and coordinated arms could dominate over Germanic skirmishing and ambush tactics. The rout stretched along miles of riverbank with massive Germanic casualties, wounding Arminius and Inguiomer and breaking the coalition’s capacity for set‑piece resistance that season. A final Germanic assault at the Angrivarian Wall was anticipated and crushed, sealing an operational triumph that politics, not arms, would suspend.

Stabilizing a restless Gaul

Before and during the German command, Germanicus held authority over all Gaul and the Rhine armies, imposing order amid post‑Augustan uncertainty and using administrative measures—including tax collection missions in 16 CE—to sustain the war effort. His capacity to calm mutinous legions in 14 CE and to keep Gallic logistics flowing for amphibious operations in 16 CE reinforced a reputation for popular leadership that resonated across provincial and military constituencies. These efforts amounted to a practical pacification and stabilization of Rome’s northwestern heartlands during a volatile dynastic transition, even if later Gallic revolts would fall to other commanders after his recall.

Triumph and recall

In May 17 CE, Germanicus celebrated a triumph in Rome that displayed captives such as Thusnelda and dramatized the recovery of standards and prestige, even as Arminius himself remained at large. The triumph’s imagery and coinage under Caligula trumpeted “Standards Recovered, Germans Defeated,” cementing the avenger’s narrative in public memory. Tiberius then reassigned Germanicus with imperium maius over the Eastern provinces, a signal of continuing dynastic favor to some observers and of jealous displacement to others, depending on the ancient source.

Eastern command and Piso

Tasked with settling Armenia, organizing Cappadocia and Commagene as provinces, and negotiating with Parthia, Germanicus achieved notable diplomatic and administrative successes that should have burnished a path to the purple. Yet a deepening conflict with the Syrian governor, Gnaeus Calpurnius Piso—sent nominally as helper but acting as antagonist—undercut Germanicus’s authority and poisoned the political atmosphere of the command. After a censure from Tiberius for visiting Egypt without authorization and a series of provocations in Syria, Piso withdrew, only for Germanicus to fall fatally ill at Antioch soon after.

Mysterious death in the East

Germanicus died at Antioch on 10 October 19 CE, convinced that Piso and Plancina had poisoned him; a subsequent Senate trial collapsed into ambiguity when Piso died, reportedly by suicide, before a definitive judgment could settle the matter. Tacitus reports rumors of sorcery and poisoning paraphernalia, but the ancient record remains divided, with some later analyses stressing how uncertain the medical and evidentiary basis for a murder verdict really is. The effect in Rome was explosive: a frenzy of grief, honors, and intensified suspicion toward Tiberius, with Sejanus’s growing influence darkening elite politics in the 20s.

The heir who should have ruled

Germanicus’s combination of military brilliance, republican‑flavored charisma, and Julio‑Claudian lineage made his accession feel almost inevitable to many contemporaries, which magnified the cultural shock of his loss. The empire had witnessed an avenger of Teutoburg who could rally soldiers, comfort provincials, and negotiate with kings—qualities that seemed to promise a balanced principate after the senatorial anxieties provoked by Tiberius’s style. In that sense the tragedy was not only personal but constitutional, depriving Rome of a leader many believed would have reconciled glory with stability.

Memory and legacy

Posthumous honors multiplied in Rome and on the frontiers, fixing Germanicus in public ritual and monumental space as an exemplary princeps‑in‑waiting. His lineage shaped subsequent reigns: Caligula was his son, Agrippina the Younger his daughter and Nero’s mother, and Claudius—his younger brother—would preside over the final recovery of the last Teutoburg eagle in his reign. As Tacitus and later artists portrayed him, Germanicus became the archetype of the virtuous Roman commander felled before destiny, an image that still frames modern assessments of his life and wars.

Campaigns of 14–16 CE: key points

- Suppressed mutinies on the Rhine in 14 CE and launched punitive raids to restore deterrence and initiative.

- Struck the Chatti and Cherusci in 15 CE, captured Thusnelda, recovered the XIX’s eagle, and extricated forces after bog‑country fighting at the pontes longi.

- Built a fleet for deep penetration in 16 CE, then won decisive victories at Idistaviso and the Angrivarian Wall before a damaging storm complicated withdrawals and a recall ended the offensive.

Vengeance and standards

- The campaigns were explicitly framed as vengeance for Varus rather than annexation beyond the Rhine, mirroring Augustan caution and Tacitean interpretation.

- Two eagles lost in 9 CE were recovered under Germanicus, with the third retrieved under Claudius decades later, completing the symbolic restitution at the Temple of Mars Ultor.

Gaul and the Rhine

- As consul and then commander over Gaul and both Rhine armies, Germanicus stabilized the northwest during the succession crisis of 14 CE and sustained the logistical foundations for the 16 CE fleet campaign.

- Tax collection missions in Gaul during 16 CE and the restoration of frontier works from the Rhine to Aliso reflected a comprehensive military‑administrative pacification.

From triumph to Antioch

- The triumph of 26 May 17 CE celebrated captives and recovered standards, projecting closure to a three‑year reckoning for Teutoburg even as Arminius remained uncaptured.

- An Eastern command produced quick diplomatic gains in Armenia, Cappadocia, Commagene, and Parthia but collided with Piso’s obstruction, an Egyptian misstep, and sudden fatal illness.

Death and doubt

- Piso’s prosecution failed to conclusively prove poisoning, with ancient narratives themselves recording doubt that the body showed unambiguous signs of veneficium.

- The result was a durable culture of suspicion around Tiberius and Sejanus and a political climate of fear amplified by treason trials in the ensuing decade.

Final assessment

Germanicus was the prince of battles whose victories on the Rhine and Weser repaired Rome’s honor, yet whose unfulfilled destiny—and the circumstances of his death—fixed him in collective memory as the heir who should have reigned. That combination of military restitution, civic charisma, and thwarted succession explains why the story still reads as a tragedy of empire as much as of one man.