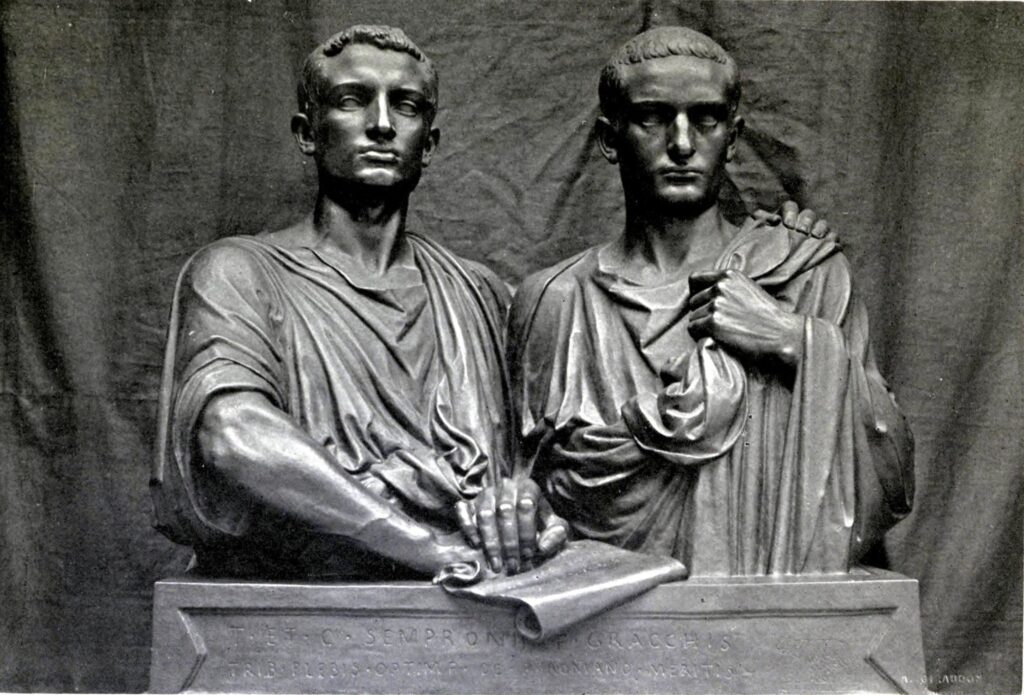

In the late Roman Republic, the names of Tiberius and Gaius Gracchus became synonymous with radical reform, populist politics, and the erosion of the old republican consensus. These two brothers, scions of a distinguished patrician lineage yet champions of the common people, ignited unprecedented political upheaval. Their reforms—Tiberius’s agrarian redistribution and Gaius’s grain laws—were not merely legislative acts; they redefined political alignments, gave birth to the populist populares faction, and provoked the first political bloodshed in the sacred precincts of Rome. As Cicero later reflected, “nihil est tam populare quam aequitatem amicis praestare”—nothing is more popular than showing fairness to friends.

Rome Before the Gracchi

The Structure of the Republic

The Roman Republic of the mid-2nd century BCE was governed by a delicate balance between the Senate, dominated by aristocratic families (optimates), and the popular assemblies, where legislation could be proposed to the plebs. The Republic prided itself on concordia ordinum, the harmony of the orders—patricians and plebeians—but this harmony concealed widening socio-economic disparities.

The Problem of Land Ownership

Following Rome’s wars of expansion, vast tracts of conquered land (ager publicus) often fell into the hands of wealthy senators, who leased them on favorable terms and converted them into latifundia worked by slaves. Small farmers, many of them citizen-soldiers who had fought in campaigns, found themselves displaced. Sallust lamented in later years: “agros colere desierunt, urbem frequentare coeperunt”—they ceased to cultivate fields and began to throng the city. Rural depopulation, urban poverty, and military manpower shortages created the conditions for reform.

Tiberius Gracchus: The Agrarian Tribune

Biography and Political Context

Tiberius Sempronius Gracchus, born circa 163 BCE, was the elder son of a respected family connected to Scipio Aemilianus. His mother, Cornelia, daughter of Scipio Africanus, famously declined the offer of marriage to King Ptolemy, preferring to raise her sons to serve Rome. Tiberius’s career began traditionally, with military service in Spain, where he witnessed first-hand the hardship of smallholders.

The Agrarian Law (Lex Sempronia Agraria)

In 133 BCE, elected as Tribune of the Plebs, Tiberius proposed a law to enforce existing limits on holding public land—500 iugera per individual—and redistribute excess land to poor citizens. His proposal was not revolutionary in law but radical in enforcement; it directly threatened the economic interests of the senatorial elite. Land commissions were appointed to oversee distribution, creating a permanent administrative machinery.

Key provisions:

- Enforcement of the landholding limit from the Licinian-Sextian laws

- Confiscation of illegally held public land

- Allocation of plots to poor citizens, revitalizing the rural base of the army

Opposition and Breakdown of Norms

Senatorial resistance was immediate. When the other tribune, Marcus Octavius, vetoed the law, Tiberius sought to depose him—an unprecedented step in Roman politics. By circumventing traditional norms, Tiberius broke with mos maiorum, the ancestral custom of consensus-driven politics.

Death of Tiberius

That same year, amid rumors Tiberius sought re-election to protect his reforms, violence erupted. In a meeting of the Senate, led by Scipio Nasica, armed supporters stormed the assembly, killing Tiberius and many followers on the Capitoline Hill—the first recorded political killings within Rome’s sacred boundaries. Polybius remarked: “primum Romae intestina arma suscepta sunt”—for the first time, internal arms were taken up in Rome.

Gaius Gracchus: The Grain Tribunate

Rise to Power

Gaius Sempronius Gracchus, nine years younger than Tiberius, entered politics with the shadow of his brother’s fate looming. Initially cautious, he gained renown through his oratory and organizational skill. In 123 BCE, he was elected Tribune of the Plebs and launched an ambitious program of reforms.

The Lex Frumentaria

Among his legislation, the grain law was most significant: the state would supply wheat to Roman citizens at a subsidized rate, stabilizing urban food supplies and securing political support. Critics argued it fostered dependency; supporters saw it as an act of justice in an era of elite exploitation.

Other reforms included:

- Extension of Roman citizenship to allies in Italy

- Transfer of jury service from senators to equites, weakening senatorial judicial dominance

- Infrastructure projects, including roads to facilitate grain distribution

Political Battles

Gaius’s reforms broadened the base of the populares. Yet his attempt to extend citizenship met fierce opposition from plebeians afraid of diluting their privileges. His enemies exploited this tension, and in his third tribunate, the Senate passed the senatus consultum ultimum, empowering magistrates to safeguard the Republic—effectively authorizing force.

Death of Gaius

In 121 BCE, cornered during an armed confrontation on the Aventine, Gaius ordered a slave to kill him to avoid capture. Thousands of his supporters were slain. The sacred boundaries of Rome were again violated by political murder. The Republic’s veneer of legality gave way to the reality of factional violence.

Populares vs Optimates

Inception of Factional Politics

Before the Gracchi, political rivalry was largely personal, not ideological. Their campaigns crystallized two enduring factions:

- Populares: Leaders appealing directly to the people’s assemblies, often bypassing the Senate

- Optimates: Conservatives defending senatorial authority and traditional aristocratic control

Strategic Innovations

The populares recognized the political potential of urban crowds, legislative assemblies, and material benefits to citizens. The optimates responded with procedural obstruction, emergency decrees, and sometimes violence—introducing a new era of confrontational politics.

Impact: The End of Republican Consensus

Decline of Concordia Ordinum

The Gracchi’s fate shattered the notion that Rome’s political system was immune to deadly conflict. As Cicero later noted, “concordia dissoluta perniciem afferre civitati solet”—when harmony is dissolved, ruin often follows for the state.

Precedent for Violence

Political murder in Rome’s sacred precincts became thinkable, setting a dangerous precedent replicated in later conflicts—from Marius and Sulla to Caesar and Pompey. Laws, once sacrosanct, became tools for factional struggle.

Institutional Consequences

- Permanent commissions and administrative bodies expanded the state’s role in economic life

- Urban masses emerged as decisive political actors

- Alliances shifted from personal patronage to ideological platforms

Conclusion: The First Populists in History

The Gracchi brothers were products of Rome’s contradictions—aristocrats championing the dispossessed, reformers who challenged entrenched privilege, pioneers of populism whose legacy mixed principle with peril. Their deaths marked not the end of their cause but the beginning of Rome’s century-long descent into civil turmoil.

From Tiberius’s agrarian vision to Gaius’s grain law, the brothers reshaped Roman politics. In their rise and fall, we see the early dynamics of mass politics and the fragility of republican institutions subjected to populist challenge. As Livy warns through the ghosts of the Gracchi, “libertatem nimis cupida, periculum invenit”—liberty, too eagerly desired, finds danger.