The Ancient Remedy for Our Modern Crisis

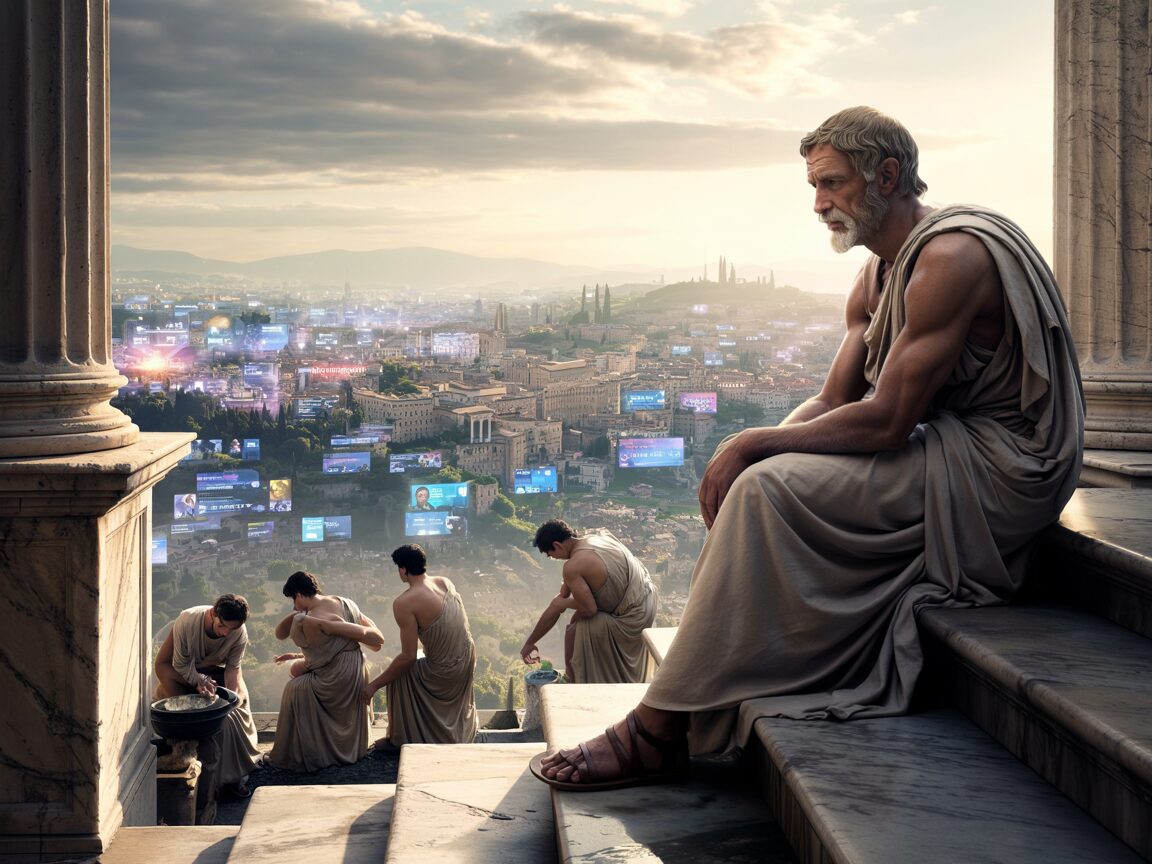

We live in the age of anxiety. Despite unprecedented comfort and technological advancement, our minds remain battlegrounds of worry, stress, and existential dread. The modern person navigates a relentless barrage of notifications, deadlines, and social pressures while the ancient mechanisms of our brains—evolved for an entirely different world—struggle to keep pace. This cognitive mismatch has created what many psychologists now recognize as an epidemic of anxiety.

Yet two thousand years ago, a Roman philosopher experienced remarkably similar psychological challenges and developed a system to address them so effective that it continues to resonate today. Seneca the Younger, statesman, dramatist, and advisor to emperors, crafted a philosophical approach to life that speaks directly to our modern condition with uncanny relevance.

“We suffer more in imagination than in reality,” wrote Seneca in one of his letters to his friend Lucilius. This observation cuts to the heart of both ancient and modern anxiety—our remarkable ability to create elaborate mental scenarios of future suffering that may never materialize. The power of Seneca’s insight isn’t merely its diagnosis of the human condition but the practical framework he provides for addressing it.

The wisdom of Seneca offers not merely intellectual understanding but actionable practices—a comprehensive system for emotional resilience that anticipates modern psychological techniques by millennia. His approach represents not just philosophy as academic exercise but philosophy as lived experience, as medicine for the soul.

Before: The Anxiety Trap of Modern Life

The modern mind exists in a state of perpetual overwhelm. We wake to news of global crises delivered instantly to devices beside our beds. We navigate workdays filled with impossible expectations of productivity and availability. We compare our unfiltered lives to the curated highlights of others. We worry about futures we cannot predict and pasts we cannot change.

This constant state of alertness keeps our nervous systems engaged in ways they were never designed to sustain. The fight-or-flight response, evolved to help us escape predators on the savannah, now activates when we see a difficult email or contemplate our financial future. Our bodies remain in states of physiological stress with no physical outlet for resolution.

The consequences manifest in our bodies and minds. Sleep becomes elusive. Concentration fractures. Relationships suffer as we bring our stressed selves to every interaction. The World Health Organization reports anxiety disorders as the most common mental health disorders worldwide, affecting nearly 300 million people. The economic burden of anxiety disorders in the United States alone is estimated in the tens of billions annually.

Modern approaches to this crisis often focus on symptom management through medication or isolated coping techniques. While these have their place, they frequently fail to address the root philosophical issues at the heart of our anxiety—our relationship with uncertainty, our attachment to outcomes, our expectations of control in an uncontrollable world.

This is precisely where Seneca’s approach proves revolutionary, offering not just techniques but a complete reorientation of perspective that addresses anxiety at its source.

After: The Stoic Mind in the Modern World

Imagine moving through life with a profound inner stability. External events—good and bad—still occur, but they no longer dictate your emotional state. You maintain perspective during crisis. You find joy in simple experiences. You accept what you cannot change while focusing energy on what you can influence.

This is the promise of the Stoic mind as cultivated through Seneca’s teachings. The transformation isn’t about eliminating emotions—Stoicism is commonly misunderstood as advocating emotional suppression—but rather about developing a healthier relationship with them. Anxiety doesn’t disappear entirely, but it no longer controls your decisions or dominates your consciousness.

Those who internalize Senecan principles develop what psychologists now call emotional resilience—the ability to recover quickly from difficulties. They build what Seneca himself might have called a “fortress of the mind,” a protected inner citadel that remains stable even when external circumstances become chaotic.

In practical terms, this manifests as reduced rumination on past events, decreased catastrophizing about the future, and increased presence in the moment. Sleep improves as the mind no longer races with possibilities when the head hits the pillow. Relationships deepen as reactive emotional patterns give way to thoughtful responses. Work becomes more focused and effective as mental energy is directed rather than scattered.

The person who embodies Seneca’s teachings navigates modern life not by escaping its challenges but by developing the inner resources to meet them with equanimity and wisdom.

The Bridge: Seneca’s Practical Path to Emotional Freedom

Seneca’s genius lies not in abstract theorizing but in practical application. His letters and essays are filled with specific exercises and perspective shifts that form a coherent system for psychological well-being. Let’s explore the core elements of this system and how they can be applied to modern life.

Premeditation of Evils: Anxiety’s Antidote

Perhaps Seneca’s most powerful technique for addressing anxiety is what he called premeditatio malorum—the premeditation of evils. This practice involves deliberately contemplating potential negative outcomes and difficulties rather than avoiding thinking about them.

This approach seems counterintuitive to modern sensibilities that often emphasize positive thinking. Yet Seneca understood something profound about human psychology: unprepared negative surprises create far more suffering than anticipated difficulties.

In his letter On Groundless Fears, Seneca writes: “Some things torment us more than they ought; some torment us before they ought; and some torment us when they ought not to torment us at all.” The premeditation of evils addresses all three categories by bringing conscious awareness to our fears.

The technique works through several psychological mechanisms. First, it reduces the shock of negative events when they occur—we’ve already mentally rehearsed this possibility. Second, it often reveals that our worst-case scenarios are survivable, even if unpleasant. Third, it highlights the gap between what might happen and what’s likely to happen, showing us that many of our fears are exaggerated.

To practice premeditation of evils in modern life, set aside time to calmly consider: What if I lose my job? What if my relationship ends? What if my health declines? Rather than spiraling into catastrophizing, approach these questions methodically. What specific challenges would each scenario present? What resources (internal and external) would you have to address them? What steps could you take to adapt?

This practice doesn’t increase anxiety but paradoxically reduces it by bringing our fears into the light of rational examination rather than leaving them in the shadows of our subconscious where they grow distorted and overwhelming.

The Dichotomy of Control: Refocusing Mental Energy

A central source of modern anxiety is our tendency to invest emotional energy in matters beyond our control while neglecting what we can influence. Seneca, following Stoic principles, emphasizes a clear distinction between what depends on us and what does not.

In his essay On Tranquility of Mind, Seneca writes about the folly of being “anxious about things which we cannot help.” He recognized that peace comes not from controlling external events but from properly directing our concerns toward our own choices, judgments, and actions.

This principle applies directly to modern anxieties. We cannot control whether our flight will be delayed, but we can control our preparation and response. We cannot control whether a pandemic emerges, but we can control our precautions and perspective. We cannot control others’ opinions of us, but we can control our integrity and values.

To apply this principle, try a simple audit of your anxieties. List your current worries, then mark each as either within your control or beyond it. For those beyond your control, practice conscious acceptance—not resignation, but recognition of reality’s parameters. For those within your control, develop specific action steps.

This reallocation of mental energy from the uncontrollable to the controllable doesn’t eliminate life’s uncertainties, but it prevents them from dominating your emotional landscape.

Voluntary Discomfort: Building Resilience Through Practice

Modern life emphasizes comfort and convenience, yet Seneca recognized that this pursuit of ease paradoxically increases our vulnerability to distress when comfort is inevitably disrupted. His solution was voluntary discomfort—deliberately experiencing inconvenience and difficulty as training for life’s inevitable challenges.

In his letters, Seneca describes practices such as wearing insufficient clothing in cold weather, eating plain food, and sleeping on a hard surface. “Set aside a certain number of days,” he advises, “during which you shall be content with the scantiest and cheapest fare, with coarse and rough dress, saying to yourself the while: ‘Is this the condition that I feared?'”

The modern application of voluntary discomfort doesn’t require extreme asceticism. Simple practices might include: taking cold showers, fasting for a day, walking rather than driving, camping with minimal equipment, or temporarily abstaining from technologies you typically rely on.

These experiences serve multiple purposes. They demonstrate our capacity to endure discomfort, reducing fear of future hardships. They create perspective by highlighting the difference between true hardship and mere inconvenience. And they generate appreciation for comforts we typically take for granted.

Voluntary discomfort functions as a vaccine for the soul—a controlled exposure to adversity that builds immunity to future suffering.

The View From Above: Gaining Perspective

Anxiety often stems from losing perspective—magnifying immediate concerns while forgetting their place in the larger context of life and the universe. Seneca frequently employs what later Stoics called “the view from above”—mentally stepping back to see our concerns from a cosmic perspective.

In Natural Questions, Seneca writes: “How many cities have either perished or shall perish? Why should you be upset if your own must fulfill its destiny?…The buildings in a single city should be viewed as you view the city itself, equally ephemeral, equally destined to fall.”

This cosmic perspective isn’t meant to diminish the importance of our lives but to place our anxieties in proper context. From the perspective of centuries or the vastness of the cosmos, many of our urgent concerns appear remarkably temporary and limited in significance.

To practice this perspective shift, try contemplating astronomical scales and timeframes. Consider that our sun is one of billions of stars in our galaxy, which is one of billions of galaxies. Reflect on the billions of humans who have lived before us and the billions who will live after us. Place your current concerns within this expanded framework.

This practice doesn’t erase immediate problems but creates a psychological spaciousness around them, preventing them from consuming our entire mental landscape.

Seneca’s Wisdom Validated: The Science of Stoic Practices

What makes Seneca’s approach particularly compelling for the modern mind is how his philosophical insights anticipate contemporary psychological research. The practices he advocated have found support in modern therapeutic approaches.

The premeditation of evils shares key elements with Cognitive Behavioral Therapy’s technique of decatastrophizing—examining worst-case scenarios to reduce anxiety about them. CBT, like Stoicism, recognizes that it’s often not events themselves but our interpretations of them that cause distress.

The dichotomy of control aligns with acceptance-based approaches in psychology, which emphasize distinguishing between what can and cannot be changed. This principle forms the foundation of the widely-known Serenity Prayer and is central to many therapeutic modalities.

Voluntary discomfort parallels exposure therapy, a well-established treatment for anxiety disorders. Both recognize that controlled exposure to feared situations reduces their power to create distress.

The view from above resembles mindfulness practices that create psychological distance from thoughts and emotions. Both approaches aim to develop an observing self that is not completely identified with immediate concerns.

These parallels don’t diminish modern psychology but highlight the remarkable psychological insight of ancient Stoic philosophy. Seneca’s approach wasn’t based on brain scans or controlled studies but on careful observation of human experience and rigorous logical analysis.

Implementing the Seneca Solution: A Daily Practice

Seneca himself would be the first to acknowledge that philosophical wisdom is valuable only when applied to daily life. “Philosophy is not a matter of engaging in a sport,” he writes to Lucilius, “it is not a means of passing the time; it moulds and builds the soul, orders our life, guides our conduct, shows us what we should do and what we should leave undone.”

To transform Seneca’s wisdom from interesting theory to life-changing practice requires consistent application. Here’s how to develop a daily Senecan approach to anxiety management:

Morning Reflection

Begin each day with a brief period of reflection. Consider what challenges you might face and prepare your mind to meet them with equanimity. Remind yourself of the dichotomy of control—what aspects of the coming day are within your power and which are not. This mental preparation sets the tone for resilient responses to whatever the day brings.

Mindful Response to Anxiety Triggers

When anxiety arises during the day, practice the Senecan pause—a moment of conscious awareness before reacting. Ask yourself: Is this within my control? What would happen in the worst case? How important will this seem from a broader perspective? These questions create space between stimulus and response, allowing for more balanced reactions.

Evening Review

End each day with self-examination. Seneca advocated reviewing the day’s events and your responses to them. Where did you maintain perspective? Where did anxiety overcome your philosophical principles? This practice isn’t about self-criticism but about learning and reinforcement. Celebrate progress while identifying opportunities for growth.

Weekly Practices

Incorporate larger Stoic exercises on a weekly basis. Perhaps practice voluntary discomfort one day per week. Set aside time for more extended premeditation of evils. Read selections from Seneca’s letters to reinforce the philosophical foundations of your practice.

This systematic approach transforms Stoicism from abstract philosophy to lived experience. As Seneca wrote, “The philosopher’s words, unlike other words, are arranged so as to affect not just the ears but the mind.”

Common Objections to the Stoic Approach

Despite its practical value, Seneca’s approach to anxiety management faces several common objections that deserve thoughtful consideration.

“Isn’t Stoicism about suppressing emotions?”

This represents perhaps the most common misunderstanding of Stoicism. Seneca doesn’t advocate eliminating emotions but developing a healthier relationship with them. He distinguishes between the initial emotional response (which he considers natural and unavoidable) and our subsequent judgment about and amplification of that response (which he believes we can influence through reason).

In his essay On Anger, Seneca writes: “The first movement is not voluntary; it is, as it were, a preparation for emotion, a threatening of it. The second movement is formed with an act of will that is not stubborn, as much as to say: ‘I must be avenged, since I have been injured,’ or ‘This man must be punished, since he has committed a crime.'”

Seneca’s approach isn’t emotional suppression but emotional intelligence—recognizing emotions, understanding their sources, and choosing wise responses rather than automatic reactions.

“Focusing on negative possibilities will increase my anxiety.”

The premeditation of evils seems counterintuitive to those accustomed to positive thinking approaches. However, Seneca understood that avoiding thoughts of difficulty doesn’t eliminate fear but drives it underground where it grows unchecked by reason.

The key distinction lies in how we contemplate potential difficulties—not through catastrophizing or rumination but through calm, rational assessment. This approach doesn’t amplify anxiety but diminishes it by bringing vague fears into clearer focus where they can be properly evaluated.

“Stoicism seems too passive in the face of injustice.”

Some interpret the Stoic emphasis on accepting what we cannot control as advocating resignation or inaction. Yet Seneca himself was deeply engaged in politics and social issues of his time. The Stoic approach doesn’t encourage passivity but rather effective action focused where it can make a difference.

Accepting reality as it currently exists doesn’t mean approving of it or failing to work for change. Rather, it means engaging with the world as it is while working toward what it could be, without the additional suffering of rage against immutable facts.

Living the Examined Life: Seneca’s Ultimate Goal

The ultimate aim of Seneca’s approach to anxiety isn’t merely stress reduction but eudaimonia—a life of flourishing, virtue, and meaning. Anxiety management serves this larger purpose by freeing mental energy for more significant pursuits.

“Life is long enough,” Seneca writes in On the Shortness of Life, “and it has been given in sufficiently generous measure to allow the accomplishment of the very greatest things if the whole of it is well invested.” Anxiety represents one of the greatest wastes of this precious resource, consuming our mental bandwidth with concerns that often never materialize.

By applying Seneca’s principles, we reclaim this mental space for purposeful living. We redirect attention from imagined disasters to present reality. We focus energy on meaningful action rather than unproductive worry. We develop perspective that allows us to distinguish between the trivial and the essential.

In this way, Seneca’s approach to anxiety doesn’t just alleviate suffering but opens the possibility of a more examined, intentional, and meaningful life—the very purpose for which philosophy was originally conceived.

The wisdom of a Roman philosopher from two millennia ago offers not just relief from modern anxiety but a comprehensive approach to living well in an uncertain world. As Seneca himself might say, the path to tranquility lies not in controlling external events but in cultivating internal strength—a lesson as relevant in our chaotic age as it was in his own turbulent times.