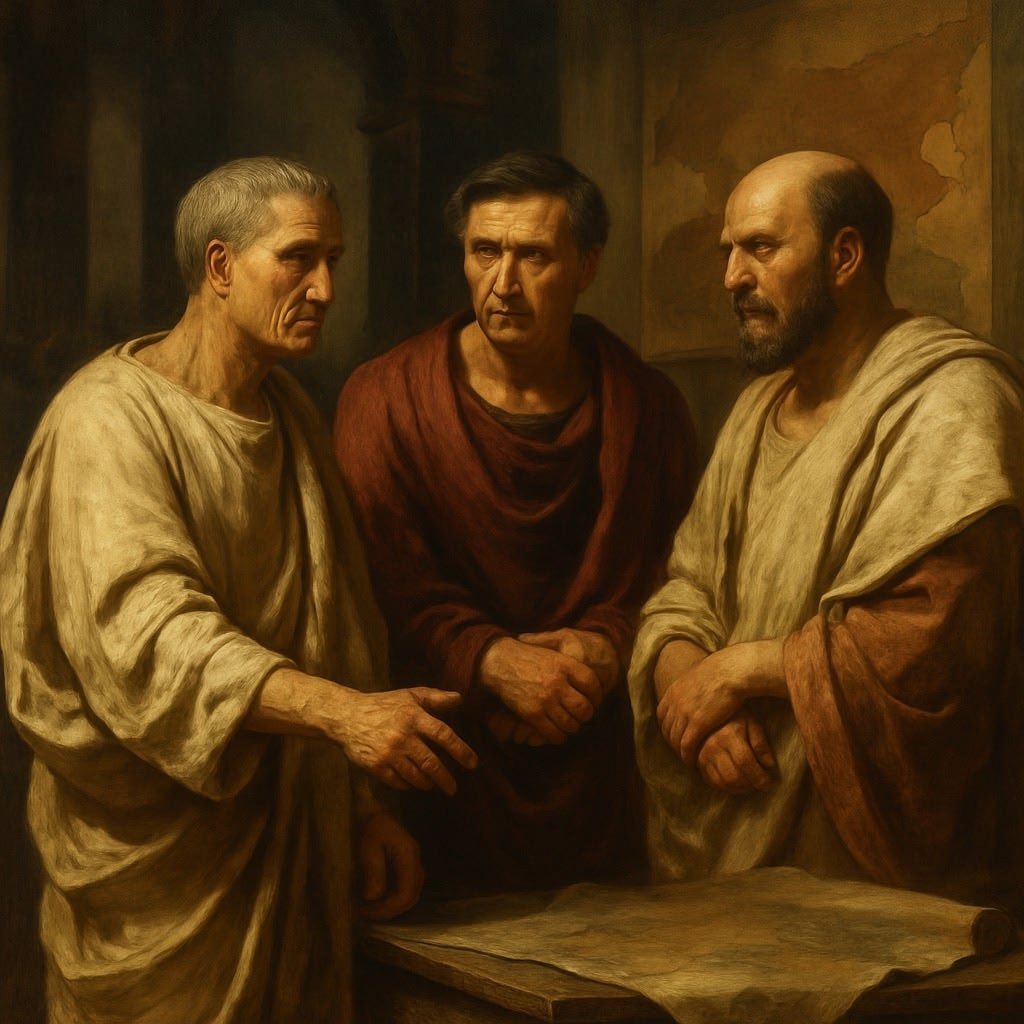

The First Triumvirate was an extralegal compact through which Caesar, Pompey, and Crassus effectively privatized the Roman state, concentrating wealth, military force, and electoral leverage in three hands and hastening the Republic’s collapse. By covertly coordinating policy, offices, and provincial commands, they bypassed senatorial checks, reshaped law through intimidation, and made personal amicitia override public legality.

A private pact

The alliance of 60–53 BCE was not an official magistracy but an informal, initially secret agreement among Pompey, Crassus, and Caesar to pool resources and push each other’s agendas through Rome’s veto-riddled constitution, which they did beginning with Caesar’s consulship in 59 BCE. Ancient and modern writers underscore its illegality and opacity: contemporaries described “three men” exercising a quasi-regnum, later sources call it a societas or conspiratio, and modern scholarship warns “First Triumvirate” is a misleading label for a private amicitia rather than a lawful board of tresviri.

Why they needed each other

Pompey sought ratification of his eastern settlements and land for veterans, Crassus wanted relief for the Asian tax contracts of the publicani, and Caesar aimed to secure the consulship and a profitable provincial command, none of which each could reliably obtain alone under senatorial obstruction. Caesar’s election alongside Bibulus for 59 BCE, combined with Pompeian and Crassian backing, supplied the leverage to break the gridlock and launch a coordinated legislative push that would serve all three.

Marriage politics

To tighten bonds, Caesar married his daughter Julia to Pompey in 59 BCE, a celebrated alliance that added a familial seal to political amicitia until Julia’s death in 54 BCE loosened that personal link. The personal glue of kinship thus reinforced, and later eroded, a pact that depended on loyalty rather than law.

Breaking legality in 59 BCE

Caesar’s agrarian program to settle Pompey’s veterans and resettle citizens advanced first in the senate and then, amid obstruction, directly to the people, where violence and intimidation marked the process, including the public humiliation of his co-consul Bibulus and the symbolic shattering of his fasces. As Bibulus withdrew to declare omens and stall business, Caesar pressed on: ratifying Pompey’s eastern settlements, aiding Crassus’s equestrian allies, and demanding oaths to his laws, actions that dramatized how a private pact could override republican norms through coordinated pressure on assemblies and magistrates.

Latin in action

The year showcased key republican terms sharpened by the pact’s methods: manipulation of the comitia, defiance of auspicia claims, expansion of personal imperium, and the use of triumphal supplicationes to amplify Caesar’s prestige, each deployed in service of a private amicitia rather than the res publica. The effect was to convert legal form into political force, with public acts serving a clandestine compact that contemporaries likened to a shared regnum.

Carving up provinces

With the tribune Publius Vatinius’s law, Caesar received a five‑year command in Illyricum and Cisalpine Gaul, soon augmented by Transalpine Gaul, delivering him a vast theater for conquest and a durable army independent of Rome’s day‑to‑day politics. The logic was simple and profound: durable imperium plus independent legions equaled political autonomy, a formula the pact reinforced for each member as it matured.

The Luca reset (56 BCE)

Amid fraying ties and Roman street violence, Caesar convened Pompey and Crassus at Luca, renewing the alliance and agreeing that Pompey and Crassus would take the consulship of 55 BCE, then receive Spain and Syria respectively, while Caesar’s Gallic command was extended five more years so that all three would hold simultaneous imperium with armies. Multiple ancient accounts attest the meeting and its outcomes—renewed amicitia, synchronized offices, and a deliberate partition of commands—while emphasizing how the pact subordinated public process to private terms.

Terms and tactics

The bargain included postponing elections so Caesar’s troops could vote, assigning Syria as a springboard for Crassus’s Parthian ambitions, maintaining Pompey’s control of Hispania in absentia, and securing Caesar’s extension in Gaul, consolidating the state’s military instruments under three coordinated hands. The result was a cartel of commands that pooled imperium, blended patronage with coercion, and sidelined the senate’s role in allocating provinces.

Consequences in arms

Caesar’s Gallic War surged forward after 59, winning record supplicationes, extending Roman reach across the Rhine, and even launching expeditions to Britain, all of which magnified his personal auctoritas and military base as a direct byproduct of the pact’s provincial strategy. The policy was clear: conquest as politics by other means, with battlefield success underpinning a private coalition’s leverage over Rome.

Parthia and Carrhae

Crassus marched from his Syrian command into Mesopotamia in 53 BCE, seeking glory and wealth, but was annihilated by Surena’s horse archers and cataphracts at Carrhae, where Roman legions in a deep square were bled by arrows and broken piecemeal, culminating in Crassus’s death during a failed parley and the loss of tens of thousands of Romans. The disaster ended the three‑way balance, removed the pact’s richest pillar, and shocked Roman politics with a humiliation second only to Cannae, while emboldening rivals and destabilizing the coalition’s internal deterrence.

Pompey’s sole consulship

Amid spiraling urban violence and political paralysis, Pompey accepted a sole consulship in 52 BCE—an extraordinary concentration of power that responded to crisis yet also underscored how the “Gang of Three” had normalized departures from collegial, elective governance. The step formalized what the pact had rehearsed: concentration of authority “for order,” but in reality for one man whose ascent had been greased by years of extralegal coordination.

From amicitia to rupture

After Crassus’s death and Julia’s earlier passing, Pompey drifted into alignment with senatorial hardliners who feared Caesar’s growing might, while Caesar’s extended imperium and legions made him increasingly independent of Roman magistrates, dissolving the pact’s internal equilibrium. By 50–49 BCE, mistrust and maneuvering culminated in open breach, and civil war followed Caesar’s fateful decision to defy recall and cross the Rubicon, the terminal symptom of a state already privatized by the triumviral method.

How three men privatized the state

The pact replaced the senate’s distributive power with private negotiation, turning provincial assignments and comital outcomes into instruments of a closed cartel, not a public constitution. It normalized coercion and spectacle—elections delayed, assemblies intimidated, omens weaponized—so that legality bowed to a conspiratio whose binding force was personal loyalty rather than law.

The decisive pivot

- It fused wealth, name, and armies into a single decision‑making core, where amicitia dictated policy and imperium, not magistracies or mos maiorum, governed outcomes.

- It weaponized provinces as power bases, enabling conquests in Gaul and an attempted eastern war, making commanders sovereign in all but title while Rome’s institutions became procedural theaters for fait accompli.

- It habituated the Republic to exceptional measures—mob intimidation, consular irregularities, and finally a sole consulship—that paved a path from “three men’s regnum” to one man’s rule.

Latin echoes

Contemporaries captured the reality with acid brevity: the arrangement was an amicitia masquerading as process, a shared regnum under republican trappings, and a conspiratio that made res publica subordinate to private pacta. In practice, the Republic’s vocabulary—comitia, auspicia, imperium, supplicationes—became instruments of a coalition whose true constitution was personal faith and force, not statute and senate.

Why the Republic died here

The First Triumvirate did not merely precede the Republic’s end; it taught Rome how to end it—by centralizing force, dividing provinces by private bargain, and erasing the distinction between public office and personal power until only civil war could decide primacy. In that sense, the “secret alliance that killed the Republic” was less an assassination than a slow privatization of sovereignty, with Carrhae’s shock and Pompey’s sole consulship marking the final stages before the leap to open autocracy.