The conference room falls silent as another executive announces their resignation. Three CEOs in five years. The board members exchange knowing glances—another leader who looked perfect on paper but couldn’t navigate the complex challenges of the organization. Meanwhile, across town, voters grimace as they watch their newly elected official, with no relevant experience, stumble through another press conference filled with empty promises and fundamental misunderstandings of the issues.

Leadership failure has become so commonplace that we’ve grown numb to it. We promote the charismatic instead of the competent, the well-connected instead of the well-qualified. We elect officials based on their campaign slogans rather than their proven capacity to govern. And then we act surprised when they fail spectacularly.

But what if there was a better way? What if, instead of hoping leaders will somehow rise to the occasion, we returned to a system that required them to prove their competence at each level before advancing? What if leadership wasn’t awarded based on wealth, connections, or charisma, but on demonstrated ability in progressively challenging roles?

Two thousand years ago, the Romans—masters of governance and administration—developed exactly such a system. Their solution to the leadership problem was elegantly practical: the cursus honorum, a structured career path that required aspiring leaders to prove themselves at multiple levels of increasing responsibility before reaching positions of true power.

In an age of leadership crises—from corporate boardrooms to the highest offices of government—this ancient Roman innovation offers a surprisingly relevant solution to our modern predicament. And understanding it might just transform how we think about selecting leaders in the 21st century.

The Leadership Crisis We Can No Longer Ignore

The statistics paint a grim picture. Executive turnover rates continue to climb. Public trust in elected officials sits at historic lows. Corporate scandals dominate headlines with depressing regularity. Failed leadership has become so common that we’ve lowered our expectations to match our disappointing reality.

Consider what happens in most modern organizations: we promote people based on their technical expertise or individual contributions, assuming these skills will translate to leadership ability. The star salesperson becomes sales manager. The brilliant programmer becomes CTO. The wealthy businessperson with no public service experience becomes a high-ranking government official. We confuse subject matter expertise with leadership capability, and then wonder why these leaders struggle to build teams, create vision, or navigate complex organizational challenges.

In government, the situation is even more problematic. We elect officials based on their ability to campaign, not their ability to govern. The skills required to win an election (fundraising, public speaking, debating) have almost nothing to do with the skills required to govern effectively (coalition building, policy expertise, administrative competence). Is it any wonder that campaign promises rarely translate to effective governance?

The consequences of this leadership vacuum are far-reaching. Organizations stagnate. Innovations die on the vine. Public trust erodes. And those at the bottom of the hierarchy—everyday employees, ordinary citizens—bear the brunt of incompetent leadership’s failures.

What makes this crisis particularly frustrating is that we know leadership isn’t innate—it’s learned through experience and practice. Yet our systems for selecting leaders rarely account for this reality. We place people in positions of enormous responsibility without ensuring they’ve developed the necessary capabilities through progressive experience.

Rome’s Radical Solution: The Cursus Honorum

To understand the brilliance of the Roman approach, we must first appreciate the scope of their challenge. At its height, the Roman Republic governed a vast territory with millions of citizens, complex diplomatic relationships, and enormous administrative demands. Leadership failure wasn’t just inconvenient—it was existentially threatening.

The Romans responded with a system called the cursus honorum—literally the “course of honors.” This structured career path required aspiring leaders to serve in a series of specifically ordered public offices, each with increasing responsibility. Critically, candidates could only advance after demonstrating competence at the previous level and reaching a minimum age requirement for each position.

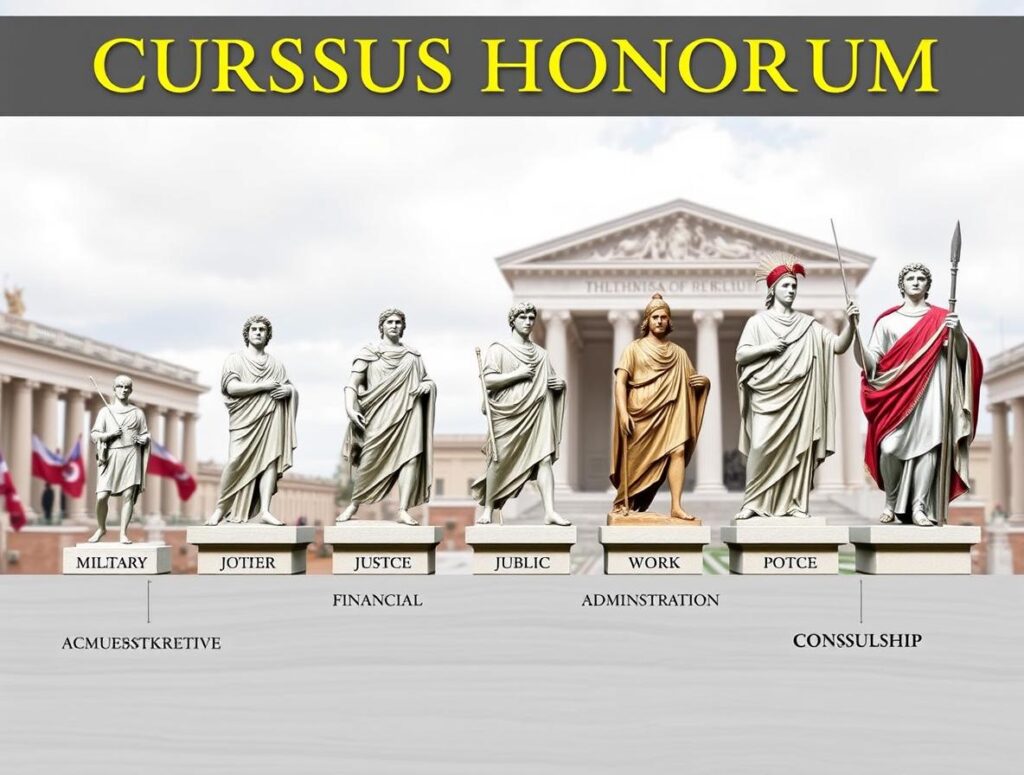

The typical cursus honorum followed this progression:

The journey began with military service—typically ten years as an officer—providing foundational experience in discipline, logistics, and leadership under pressure. After military service, an aspiring leader would serve as a quaestor (financial administrator), managing public finances and gaining essential fiscal experience. Only after demonstrating competence in financial management could one advance to aedile, overseeing public works, infrastructure, and public games—essentially running the civic services citizens depended upon daily.

Next came the role of praetor, administering justice and commanding armies—roles requiring sophisticated judgment and leadership skills. Finally, after proving oneself at each previous level, one might reach the consulship—the highest elected office, equivalent to our modern heads of state—but only after reaching age 42 and successfully holding each prerequisite office.

This methodical progression ensured that by the time someone reached the highest offices, they had demonstrated competence in finance, public administration, justice, and military leadership. They understood governance from multiple perspectives and had been tested in progressively challenging environments.

Most importantly, the system created leaders with practical wisdom—the kind that comes only from facing real challenges at increasing levels of complexity and responsibility. It wasn’t theoretical knowledge they gained, but embodied expertise through direct experience.

The Surprising Advantages of Rome’s Leadership Pipeline

What made the cursus honorum so effective wasn’t just that it created experienced leaders—it’s that it created well-rounded ones. Modern organizations often develop specialists who understand one narrow slice of operations. Roman leaders, by contrast, developed comprehensive understanding by rotating through different types of responsibilities.

This system created several distinct advantages that remain relevant today:

First, it established objective qualification standards. Leadership positions weren’t awarded based on wealth, family connections, or popularity alone—though these certainly helped Romans advance. Candidates still needed to complete the required offices in sequence and demonstrate basic competence at each level. This created at least a minimum standard of qualification for high office.

Second, it allowed for performance evaluation at multiple levels. Rather than promoting someone directly from individual contributor to senior leader, the Romans could evaluate performance at each progressively responsible position. This created numerous opportunities to identify both strengths and weaknesses before someone reached positions of tremendous power.

Third, it built cross-functional understanding. A leader who had managed finances as a quaestor, infrastructure as an aedile, and justice as a praetor developed a holistic understanding of governance that no specialist could match. This created leaders capable of seeing the big picture and understanding how different aspects of governance interconnected.

Fourth, it aligned skills with responsibilities. Each office in the cursus honorum developed specific capabilities relevant to higher offices. Military service built discipline and tactical thinking. Quaestorship developed financial acumen. The aedileship built administrative capabilities. The praetorship honed judgment and executive decision-making. By the time someone reached the consulship, they had developed the precise mixture of skills needed for that role.

Perhaps most importantly, the system created legitimate authority. Leaders who had risen through the ranks earned respect because everyone knew they had proven themselves at multiple levels. Their authority came not just from their title, but from their demonstrated competence over years of public service.

When Rome Abandoned Merit: Cautionary Tales

The effectiveness of the cursus honorum becomes even clearer when we consider what happened when Rome abandoned it. As the Republic transitioned to Empire, exceptions to the traditional career path became increasingly common. These exceptions offer revealing case studies in the dangers of elevating untested leaders.

Consider the contrast between Augustus and Caligula. Augustus (born Octavian) generally followed the traditional path of advancement, holding various offices and military commands that prepared him for ultimate leadership. Though he eventually became Rome’s first emperor, his leadership was marked by administrative competence, pragmatic policy, and relative stability. His success stemmed partly from the progressive experience he gained before taking power.

Caligula, by contrast, became emperor with almost no administrative or military experience. Elevated based on his family connection to the popular general Germanicus, he bypassed the traditional cursus honorum entirely. The result was one of history’s most notorious leadership disasters—a reign marked by incompetence, cruelty, and ultimately, assassination after just four years.

When Rome strictly adhered to its merit-based system, it produced leaders like Cicero—who rose from modest origins to become one of Rome’s greatest statesmen precisely because the system allowed talent to be recognized and developed through progressive challenges. When Rome abandoned merit for nepotism and hereditary succession, it accelerated its decline.

The lesson is clear: systems that elevate untested leaders based on wealth, connections, or charisma rather than demonstrated competence produce catastrophic leadership failures. The further Rome drifted from its merit-based advancement system, the more its governance suffered.

Reimagining Modern Leadership Selection

What would it look like if we applied Rome’s progressive leadership development approach in modern contexts? While we can’t directly transplant an ancient system, we can adapt its core principles to contemporary challenges.

In business, this might mean creating structured leadership development paths that require experience in multiple functional areas before reaching executive positions. Rather than promoting the brilliant engineer directly to CTO, organizations might require rotations through team leadership, product management, and operational roles first. This cross-functional experience would create leaders with broader perspective and proven capabilities at multiple levels.

For government, the implications are even more significant. What if higher elected offices required previous experience in local government or civil service? What if candidates for national leadership needed to demonstrate competence in progressively responsible public roles before being eligible for the highest offices? This wouldn’t necessarily mean creating rigid requirements, but rather developing pathways that encourage and reward progressive public service experience.

Some modern organizations have already embraced elements of this approach. The military still largely promotes based on progressive experience and demonstrated competence at multiple levels. Some civil service systems use structured career paths with increasing responsibility. Certain corporations have created leadership pipelines that require rotational experience across functions.

These contemporary examples suggest that Rome’s basic insight—that leadership capability should be developed and demonstrated across multiple contexts of increasing responsibility—remains valid. The specific offices might change, but the principle of progressive development still applies.

Implementing a Modern Cursus Honorum

How might organizations and institutions begin moving toward a more structured, experience-based approach to leadership development? Several practical steps could move us in this direction:

First, clearly define leadership progression paths that develop complementary skills. Just as Rome’s sequence built financial, administrative, and executive capabilities in sequence, modern organizations can create paths that systematically develop crucial leadership competencies through progressively challenging roles.

Second, require cross-functional experience for senior positions. Before someone can lead an entire organization, they should understand its various components. Rotational assignments, cross-functional projects, and temporary role exchanges can build this broader perspective.

Third, create meaningful evaluation at each leadership level. The Roman system worked because performance was assessed at each stage. Modern organizations need substantive performance evaluation that goes beyond superficial metrics to assess true leadership effectiveness at each level.

Fourth, balance merit with accessibility. Rome’s system had significant flaws—it was often restricted to patricians and the wealthy. Modern leadership development systems must create accessible pathways for talent from all backgrounds while still maintaining rigorous standards.

Fifth, reward completion of development paths. Organizations can create incentives that recognize and reward leaders who invest in broad development rather than specialized advancement. This might include promotion preferences, compensation adjustments, or public recognition for those who develop cross-functional expertise.

For government, we might consider creating more formalized paths to higher office that encourage experience at local and state levels before national positions. While we wouldn’t want to create rigid requirements that limit democratic choice, we could develop incentives and norms that value progressive public service experience.

The Courage to Demand Qualified Leadership

The most significant barrier to implementing Rome’s merit-based approach isn’t structural—it’s cultural. We’ve become accustomed to leadership selection based on charisma, connections, and communication skills rather than demonstrated competence across multiple domains. Changing this requires a fundamental shift in what we value in leaders.

This shift demands courage—from boards of directors who must prioritize proven capability over charismatic presentations, from voters who must value substantive experience over compelling campaign narratives, and from organizations that must invest in long-term leadership development rather than quick-fix executive hiring.

It also requires patience. Rome’s system recognized that leadership development takes time—often decades. There are no shortcuts to developing the wisdom that comes from progressive experience. In a world obsessed with immediate results, the discipline to invest in long-term leadership development represents a radical act of organizational wisdom.

Perhaps most importantly, it requires honesty about our current leadership crisis. We must acknowledge that our existing approaches to selecting and developing leaders are failing us. The evidence surrounds us—in failed corporate transformations, in dysfunctional governments, in organizations that lurch from one leadership disaster to another.

A New Cursus Honorum for Modern Times

The Romans understood something we’ve forgotten: leadership isn’t just about having the right personality or technical skills—it’s about developing wisdom through progressive challenges successfully overcome. Their cursus honorum wasn’t perfect, but its core insight remains powerful: great leaders aren’t born or made in a moment—they’re developed through structured experiences that build capabilities progressively.

As we face unprecedented leadership challenges—from climate change to technological disruption to social transformation—we need leaders with the depth of capability that only comes from proven performance at multiple levels. We need modern versions of Rome’s pragmatic, experience-based leadership development system.

This doesn’t mean blindly copying an ancient model. It means adapting its core principles to our contemporary context. It means creating leadership pathways that value progressive experience and demonstrated competence. It means rejecting the false promise of untested leadership and embracing the proven wisdom of merit-based advancement.

The next time you watch an inexperienced leader struggle with challenges they clearly don’t understand, remember that there is an alternative. The Romans showed us a better way 2,000 years ago. Perhaps it’s time we learned from their example and created our own modern cursus honorum—a leadership pathway based not on who you know or how you speak, but on what you’ve proven you can do at each level of increasing responsibility.

The future of our organizations, our governments, and perhaps our civilization depends on getting leadership right. Rome’s ancient wisdom offers us a path forward—if we have the courage to follow it.