Cicero defended the Roman Republic with words as weapons, using oratory to expose conspiracies, confront strongmen, and articulate a constitutional ideal whose influence has outlived the men who killed him. From the Catilinarian orations to the Philippics, his rhetoric mobilized institutions and public opinion against would‑be dictators, even as his own death in the proscriptions showed both the power and the limits of eloquence in an age of civil war.

The stakes of speech

Cicero was a Roman statesman, lawyer, scholar, and writer who sought to uphold republican principles during the violent crises that ended the Roman Republic, and he was remembered in antiquity and beyond as Rome’s greatest orator and an innovator of Latin prose style. In a polity without mass media or standing police, persuasion in the Senate and Forum served as civic armor and institutional glue; Cicero’s strategy was to make the case that law, custom, and the commonwealth could still restrain ambition backed by arms.

The Catilinarian crisis (63 BCE)

A republic on edge

In 63 BCE, after multiple electoral defeats, Lucius Sergius Catilina organized a conspiracy that mixed bankrupt elites, disaffected veterans, and struggling farmers to overturn the republic, triggering a state of emergency and the Senate’s last decree, the senatus consultum ultimum. Intelligence links to an armed uprising in Etruria and assassination plots in Rome forced the consuls—chiefly Cicero—to act, setting the stage for a pivotal confrontation in the Senate.

Four speeches, one objective

Cicero’s First Catilinarian, delivered in the Temple of Jupiter Stator, accused Catiline to his face and urged him to leave the city, framing the crisis as treason against the res publica and rallying senatorial opinion with a theatrical denunciation still remembered for lines like “O tempora, o mores”. Subsequent speeches informed the people, exposed the Allobroges correspondence, and culminated in a Senate debate that—under emergency powers and after Cato’s intervention—endorsed the extrajudicial execution of the arrested conspirators, a decision Cicero publicly announced with “vixerunt” and that helped earn him the title pater patriae while seeding future legal peril.

Why it mattered

The Catilinarians demonstrated how calibrated invective, disclosure of evidence, and appeals to precedent could channel fear into coordinated state action, averting open urban war by delegitimizing a revolutionary coalition before it could coalesce. They also set a precedent Cicero would wrestle with for the rest of his life: defending emergency measures as necessary for the republic while defending himself against charges that those measures violated the very legality he championed.

The Philippics against Antony (44–43 BCE)

After Caesar’s assassination

Following Caesar’s murder in March 44 BCE, Mark Antony moved to consolidate Caesarian power, Octavian arrived to press his adoptive inheritance, and the Senate wavered between compromise and confrontation, creating a volatile triangle of ambition and legality. Cicero reentered politics with fourteen speeches he named Philippics—after Demosthenes’ attacks on Philip II—seeking to rally the Senate and people against Antony as a tyrannical threat to the res publica.

Rhetoric as resistance

The Philippics denounced Antony’s abuses, praised Octavian as a temporary ally, and secured senatorial votes that declared Antony an enemy of the state and mobilized armies under the new consuls with Octavian’s support, briefly restoring constitutional initiative to the Senate. Modeled on Greek exempla but keyed to Roman law and memory—including comparisons to Catiline—the speeches wielded history, character assassination, and legal framing to turn Antony’s claims to continuity with Caesar into a liability.

Consequences and limits

Military victories at Forum Gallorum and Mutina cost the Senate both consuls, leaving Octavian in possession of the army and leverage that he used to force his own consulship and then reconcile with Antony and Lepidus in the Second Triumvirate, which promptly instituted proscriptions. Thus the Philippics achieved procedural triumphs but could not outpace battlefield contingencies and coalition shifts, illustrating how eloquence could ignite collective action yet remain vulnerable to the arithmetic of legions.

A death staged on the rostra

Proscription and pursuit

When the triumvirs formalized their pact in late 43 BCE, they exchanged enemies to proscribe, and Cicero—whose speeches had shaped the anti‑Antonian moment—was added to the list, hunted as one of the most prominent targets. He was captured near Formiae on December 7, 43 BCE, submitting to execution in a gesture of stoic acceptance that ancient sources preserved as emblematic of his identity as an orator and statesman.

Head and hands displayed

By Antony’s order, Cicero’s head and hands—the instruments of the Philippics—were nailed to the rostra, turning the Republic’s premier platform of speech into a tableau of intimidation and a message about the costs of rhetorical leadership against armed coalitions. The spectacle crystallized the theme of his career: words could marshal institutions and memory, but words alone could not survive a reconfigured monopoly on violence.

Father of Latin eloquence

Craft and method

Trained by Molon of Rhodes and blending Attic clarity with Asiatic amplitude, Cicero rejected rigid stylistic camps to craft the periodic sentence and calibrate cadence, humor, invective, and pathos to the moment and the audience, transforming Latin prose into a supple instrument of law and philosophy. His orations and treatises, including works like De oratore and Orator, codified a toolkit that united breadth of cultural reference with forensic technique, setting the benchmark for rhetorical education for centuries.

Language and legacy

As a philosopher and translator, Cicero coined or standardized Latin terms for Greek concepts—such as qualitas and quantitas—expanding Latin’s capacity to handle abstract thought while shaping a vocabulary later inherited by European intellectual traditions. Ancient and early modern authorities alike treated him as the emblem of eloquence, and his letters and speeches became both sources for Roman history and models for civic discourse, from Augustine and Quintilian to Renaissance humanists and Enlightenment political theorists.

Why his words endure

Ciceronian rhetoric fused constitutional principle, moral argument, and literary artistry into public action, demonstrating how speech could teach audiences what law and liberty meant as it mobilized them to defend both. Even where his politics faltered, the architecture of his language remained a durable technology of citizenship, replicable across eras less vulnerable to proscriptions than his own.

The orator versus would‑be dictators

Words as civic armor

Against Catiline, Cicero made the Senate see treason as a present danger and the people see patience as complicity, transforming suspicion into a mandate to secure the city without unleashing indiscriminate violence. Against Antony, he made tyrant a Roman category rather than a Greek cautionary tale, tying immediate votes to long memories and attempting to bind armies to law by binding their commanders to honor.

The limits of eloquence

Because the late Republic’s decisive contests were fought by coalitions of generals, not stable parties or courts, eloquence could trigger victories but could not institutionalize them without durable alignments of armed power and legal authority. Cicero’s execution by the triumvirs—despite the Senate’s temporary ascendancy—exposes that gap, even as his words continued to furnish the frameworks through which later societies narrated liberty, law, and civic duty.

Catilinarians: form and force

Audience and stagecraft

By staging the First Catilinarian as a moral indictment before the Senate and framing the subsequent speeches for the people, Cicero created a two‑front rhetorical campaign that harmonized elite consent with popular alertness. The choreography—publicly advising Catiline to leave while privately monitoring the Allobroges to secure letters—allowed speech to shape events without blurring the line between oration and policing.

Content and consequences

The speeches reframed Catiline’s circle as a cross‑class conspiracy of desperation rather than reform, invalidating its appeal to the disaffected by associating it with bankruptcy and crime rather than justice or relief. Their success, however, left Cicero exposed to charges of illegality for executing citizens without trial, a political vulnerability adversaries would exploit years later, showing how rhetorical victories can generate legal liabilities.

Philippics: imitation and innovation

Demosthenes in Rome

By borrowing the name and some strategies from Demosthenes, Cicero situated Antony in a lineage of continental strongmen, making Greek history a mirror for Roman present while adapting the argument to Roman law and offices. The result was hybrid rhetoric—part forensic, part deliberative—that sought not only to judge Antony but to legislate collective action against him.

The pivot to Octavian

A core tactic of the Philippics was to elevate Octavian as a constitutional counterweight, underestimating his ambition while overestimating the Senate’s ability to steer a nineteen‑year‑old with an army, a misjudgment that oratory could not correct once battlefield facts changed. The speeches won motions and mobilizations, but the deaths of both consuls at Mutina left Cicero without the magistrates needed to anchor those wins to lasting command.

Law, violence, and memory

Emergency powers and their price

From the SCU in 63 to the enemy‑of‑the‑state declarations in 43, Cicero used legal instruments to constrain unlawful force, yet each invocation of emergency logic risked normalizing exceptional remedies future rivals could wield against him. His career thus maps the paradox of republican self‑defense: saving legality by temporarily bending it, at the risk that adversaries will remember the bends better than the purpose.

The Forum as theater

That Cicero’s head and hands were displayed on the rostra—the Republic’s speaking platform—was not only revenge but a counter‑argument enacted in space, insisting that in a militarized polity bodies, not words, would deliver the last word. Yet precisely because the image was so legible, it ensured that his story would be retold as a martyrdom for speech, a narrative that continued to empower the very medium it aimed to silence.

Why Cicero matters now

Constitutional imagination

Cicero’s oratory offers a grammar for thinking about how institutions can respond to internal threats without self‑annihilation, balancing vigilance with restraint and legal form with moral claim. The Catilinarians and Philippics remain case studies in mobilizing collective judgment under pressure, illustrating both what rhetoric can accomplish and what it cannot secure without stable power behind it.

Civic education

Because his language codified terms for philosophy and public virtue, Cicero helped make Latin—and by inheritance many European languages—capable of public reason, a legacy visible in later humanist education and political theory. Reading him thus trains not only taste but citizenship, connecting eloquence to ethics across time.

Suggested visuals

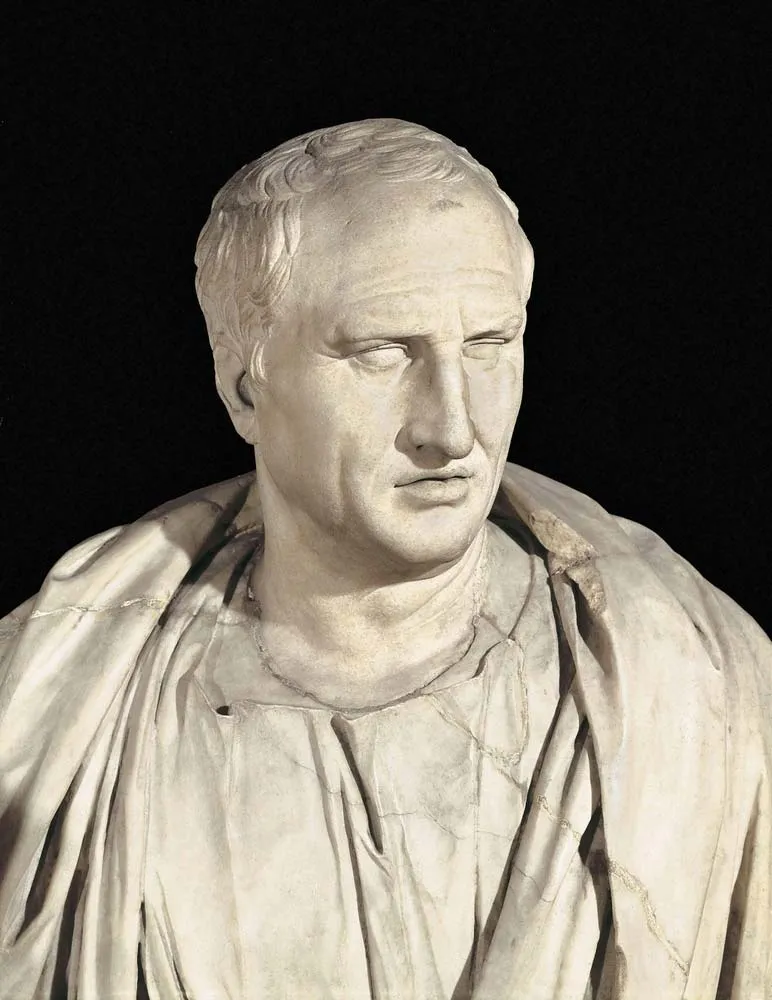

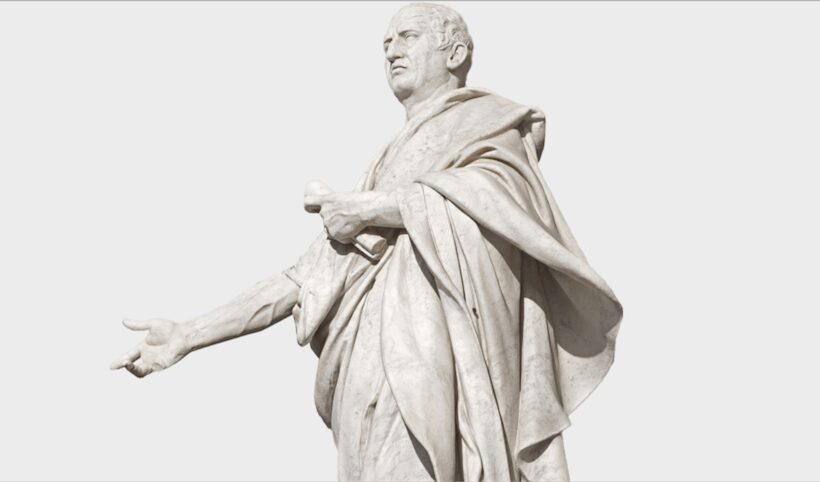

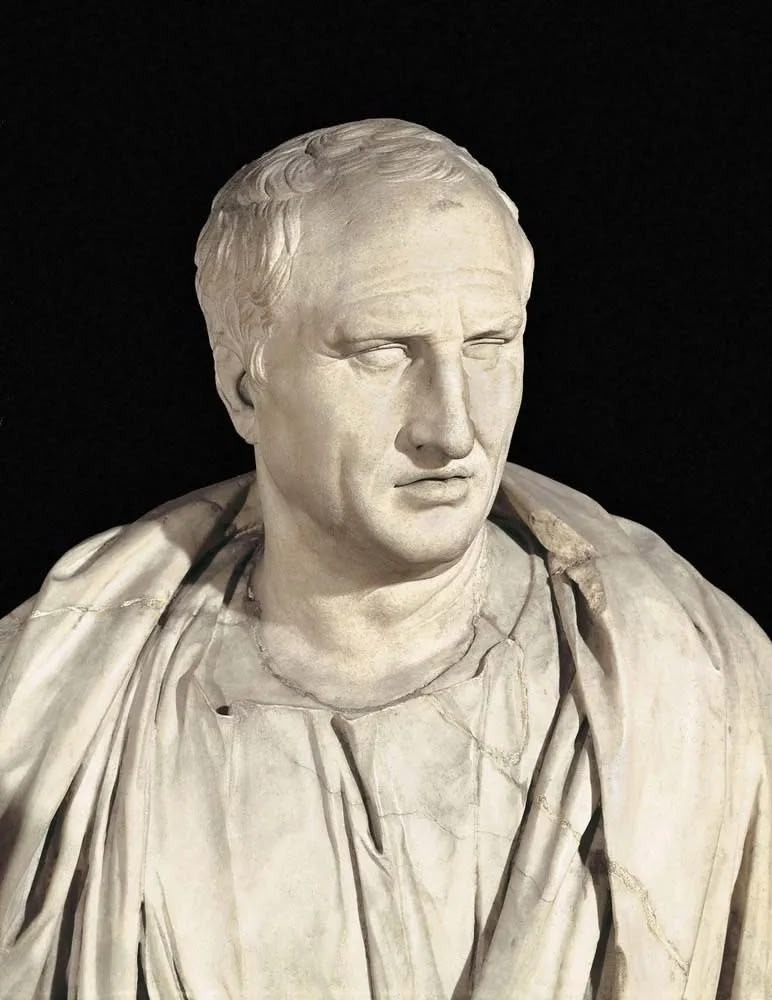

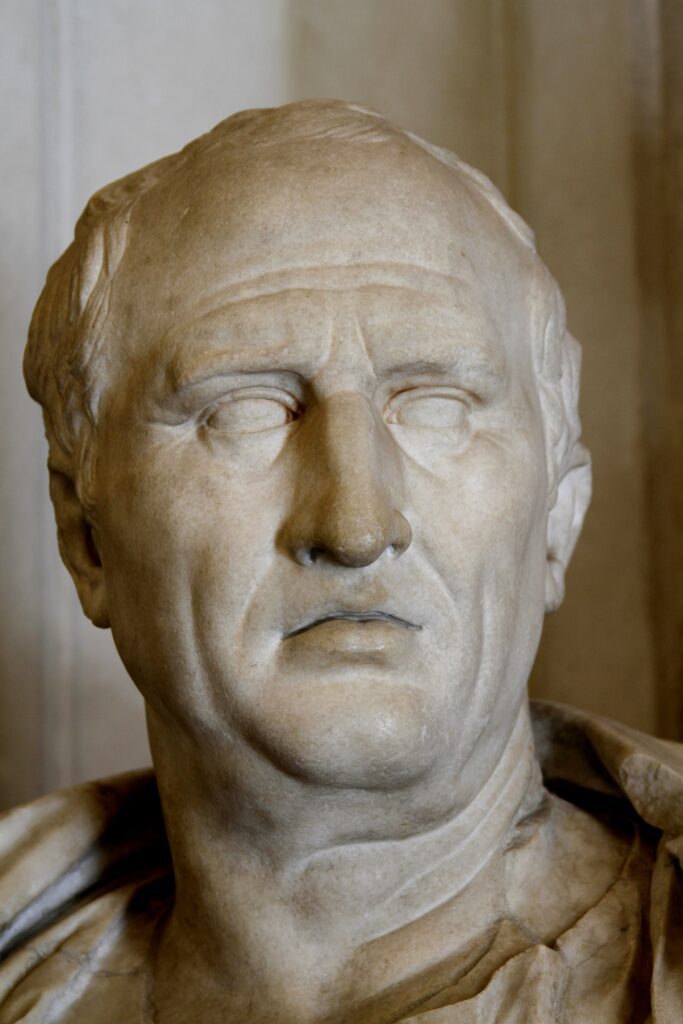

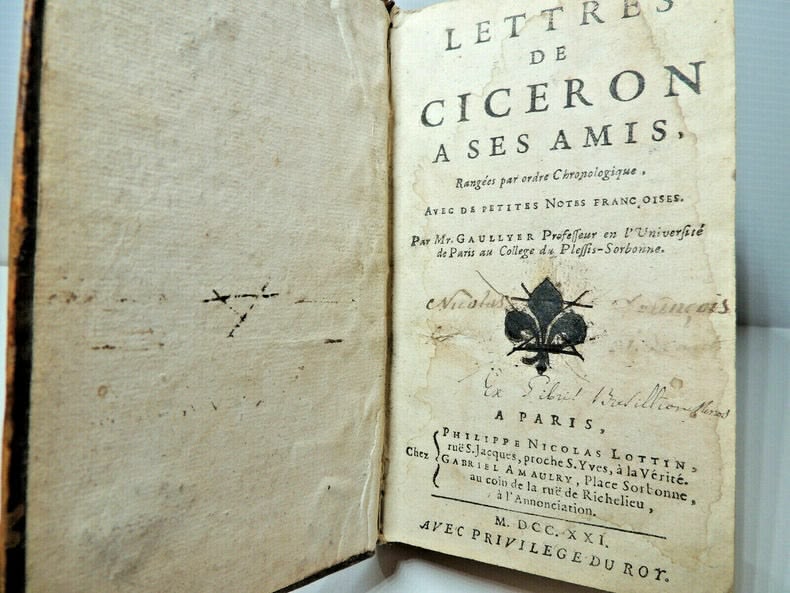

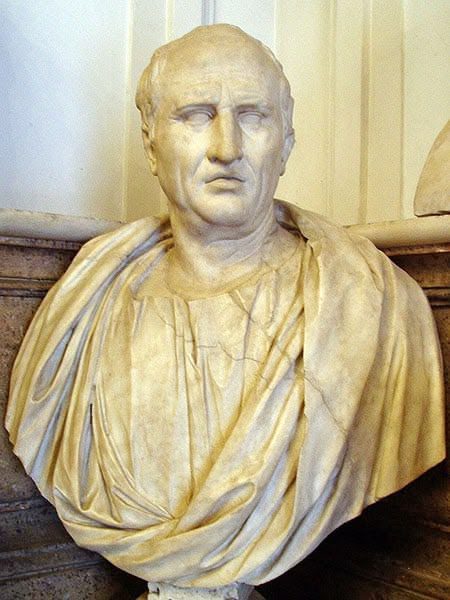

- Busts of Cicero from the Capitoline or Vatican collections to humanize the orator and visually anchor his public identity in Roman marble portraiture.wikipedia

- Photographs or facsimiles of medieval manuscripts or early printed editions of Cicero’s speeches and letters to underscore textual transmission and the breadth of his surviving corpus.britannica

- Reconstructions or diagrams of the Roman Forum and the rostra to situate the Catilinarians and the display of his head and hands within the topography of Roman public life.

Further reading anchors within his corpus

Orations and treatises

The speeches against Catiline and Antony can be read alongside De oratore and Orator to see how theory and practice inform each other in Cicero’s thinking about audience, style, and civic purpose. Taken with the letters, they yield a uniquely granular archive for the Republic’s last decades, blending literature with history in ways few figures allow.

Life and times

Biographical syntheses emphasize his status as novus homo, his oscillations between principle and compromise, and his final misreading of Octavian, all of which sharpen the drama of an orator who tried to make the constitution speak louder than the sword. That tension—between voice and force—remains the core of why Cicero’s career is studied wherever republican ideals are under strain.