Lucius Annaeus Seneca navigated one of history’s most dangerous tightropes—advising the emperor Nero while preaching Stoic detachment from power and wealth. His philosophical writings on virtue, resilience, and the art of living well have influenced Western thought for two millennia. Yet his life raises an enduring question: can a philosopher serve tyranny without compromising his principles?

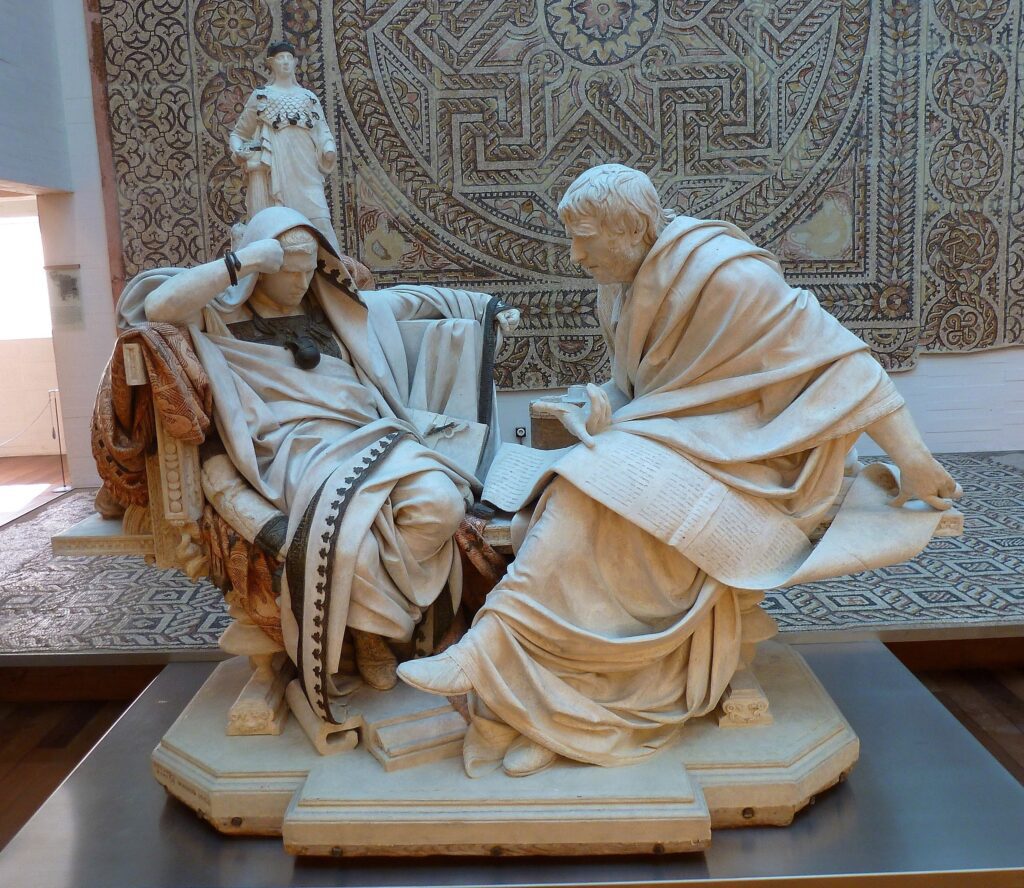

Picture Rome, 65 CE. In a villa outside the city, a 69-year-old philosopher opens his veins at the emperor’s command. Seneca the Younger, once the most powerful advisor in the empire, dies by forced suicide—victim of the very ruler he had tutored since childhood. His final hours were spent consoling his weeping wife, dictating philosophical reflections to scribes, and demonstrating the Stoic calm he had preached for decades.

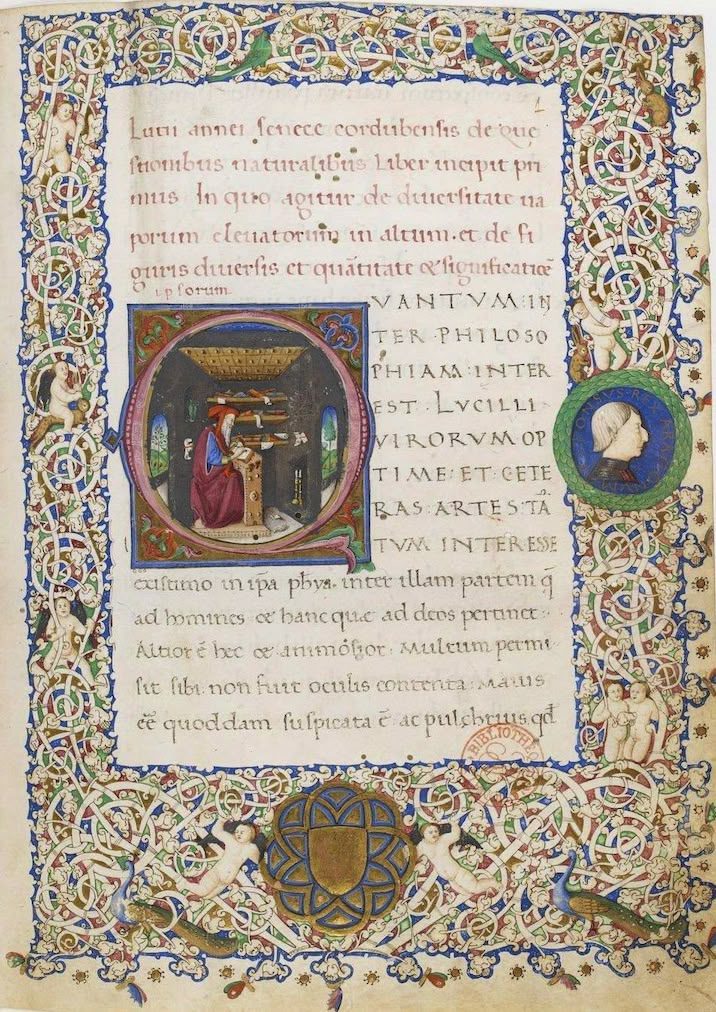

This scene crystallizes Seneca’s paradox. He amassed enormous wealth while writing that riches corrupt the soul. He counseled mercy while justifying his emperor’s matricide. He championed reason while navigating a court fueled by paranoia and violence. Yet his essays, letters, and tragedies—works like Letters to Lucilius, On the Shortness of Life, and On Anger—became foundational texts of Stoic philosophy, shaping thinkers from Marcus Aurelius to Montaigne to modern readers seeking practical wisdom.

Can we separate the philosopher’s timeless insights from the courtier’s compromises? This article traces Seneca’s trajectory from Spanish provincial to imperial tutor, from exiled philosopher to millionaire statesman, examining how he reconciled philosophy with power, why his relationship with Nero collapsed, and how his contradictions illuminate both the possibilities and limits of applied ethics. His life remains a case study in the costs of proximity to power—and the enduring relevance of Stoic thought.

From Córdoba to Rome: the making of a philosopher-courtier

Seneca was born around 4 BCE in Córdoba, Roman Spain, into a wealthy equestrian family. His father, Seneca the Elder, was a renowned rhetorician who moved the family to Rome when Lucius was young. The household prized eloquence, debate, and intellectual achievement—training grounds for careers in law and politics.

Young Seneca studied rhetoric and philosophy under Stoic and Neo-Pythagorean teachers. Stoicism, founded in Athens centuries earlier, taught that virtue is the sole good, that external events lie beyond our control, and that reason should govern emotion. These ideas would anchor Seneca’s worldview, though his interpretation remained flexible, borrowing eclectically from other schools.

He launched a political career, entering the Senate and establishing himself as a gifted orator. But in 41 CE, the emperor Claudius banished him to Corsica on charges—likely fabricated—of adultery with the emperor’s niece. The exile lasted eight years. Cut off from Rome’s libraries, salons, and power centers, Seneca wrote consolatory essays, including To Helvia, On Consolation, addressed to his mother. He framed his suffering philosophically: exile merely changes location, not the self; the wise man carries his virtues wherever he goes.

In 49 CE, Claudius’s wife Agrippina secured Seneca’s recall. She needed a tutor for her 12-year-old son, Nero, whom she intended to make emperor. Seneca’s rhetorical skill, philosophical gravitas, and political malleability made him ideal. He returned to Rome, entered the imperial household, and began shaping the mind of a future ruler—a position offering both influence and danger.

The golden years: philosopher as kingmaker

When Claudius died in 54 CE—possibly poisoned by Agrippina—Nero, barely 17, became emperor. Seneca, alongside the Praetorian prefect Burrus, effectively governed the empire for the next five years. Historians call this period the quinquennium Neronis—Nero’s golden quinquennium—a time of relative competence, restrained foreign policy, and domestic stability.

Seneca drafted Nero’s speeches, including his inaugural address to the Senate, which promised constitutional governance and respect for senatorial privilege. He advised on policy, mediated between factions, and cultivated an image of the young emperor as enlightened and moderate. Behind the scenes, he accumulated immense wealth—estates, vineyards, loans that made him one of Rome’s richest men.

This wealth became a source of criticism. How could a Stoic philosopher, who wrote that “the wise man needs nothing,” own hundreds of citrus-wood tables and lend money at interest across the empire? Seneca addressed the contradiction directly in essays like On the Happy Life. Wealth, he argued, is morally neutral—an “indifferent” in Stoic terms. The wise man can possess riches without being enslaved by them, using them for good while remaining detached. Critics, then and now, found this unconvincing. The satirist Dio Cassius later mocked Seneca’s “preaching poverty from a palace of gold.”

Yet Seneca’s influence during these years was real. He restrained some of Nero’s worst impulses, promoted legal reforms, and stabilized imperial finances. He also wrote prolifically: essays on anger, clemency, providence, and the brevity of life. On Clemency, addressed to Nero, argued that mercy distinguishes a ruler from a tyrant—a pointed lesson in an age when emperors routinely executed rivals. Whether Nero internalized these teachings is another question.

The unraveling: matricide, fire, and philosophical compromise

In 59 CE, Nero murdered his mother, Agrippina. The relationship had soured—she objected to his mistresses, his artistic pretensions, his independence. Nero, advised by Seneca and Burrus, orchestrated her assassination. When the deed was done, Seneca drafted a letter to the Senate justifying it, claiming Agrippina had plotted against her son and that Nero acted in self-defense.

This was Seneca’s darkest moment. No amount of Stoic casuistry could obscure the crime or his complicity. He had chosen political survival over moral integrity. Some scholars argue he saw no alternative—opposing Nero meant death, and perhaps Seneca believed he could still moderate the emperor’s excesses. Others see it as unforgivable hypocrisy. The philosopher who had written eloquently about conscience and virtue had become an apologist for matricide.

After 62 CE, when Burrus died, Seneca’s influence waned. Nero replaced Burrus with Tigellinus, a ruthless favorite who encouraged the emperor’s cruelty and megalomania. Seneca requested retirement. Nero, suspicious but not yet hostile, allowed him to withdraw from court. Seneca retreated to his estates, claiming to live simply—though “simply” for Seneca still meant considerable luxury.

In 64 CE, Rome burned. Nero blamed Christians, but rumors circulated that he had started the fire to clear land for his Golden House. The catastrophe destabilized the regime. By 65 CE, conspirators, including senators and officers, plotted to assassinate Nero in the Pisonian Conspiracy. Seneca’s involvement remains unclear—he may have known of the plot or simply been suspected due to his connections. When the conspiracy unraveled, Nero ordered his former tutor to commit suicide.

Seneca complied, opening his veins in a scene his biographer Tacitus described in detail. He comforted his wife, Paulina, dictated philosophical reflections, and died slowly. Tacitus noted his composure: “He endured death as he had taught others to endure it.” It was a consciously Stoic performance—a final demonstration that the philosopher could master his fate, even when that fate was imposed by a tyrant.

Stoicism versus reality: the debate over Seneca’s legacy

Seneca’s life has always provoked debate. Was he a hypocrite who preached virtue while enabling vice? Or a pragmatist who did his best in impossible circumstances?

Ancient critics condemned him harshly. Dio Cassius called him a “pretentious moralist” whose wealth and flattery of Nero discredited Stoicism. Quintilian, a later rhetorician, admired Seneca’s prose but thought his philosophy shallow. Early Christian writers, however, embraced him—Jerome even circulated forged letters suggesting Seneca corresponded with Saint Paul. His emphasis on conscience, humility, and the soul’s immortality resonated with Christian ethics.

Medieval and Renaissance thinkers revered Seneca as a model of wisdom. Petrarch, Erasmus, and Montaigne quoted him extensively. His essays on anger, grief, and time management spoke to educated elites navigating court politics. Montaigne, himself a former magistrate, sympathized with Seneca’s dilemmas, writing that “philosophy is not made to resist such violent passions.”

Modern scholars remain divided. Some, like the classicist Miriam Griffin, argue that Seneca genuinely tried to apply Stoic principles to governance, accepting wealth as a tool rather than an end. His writings on clemency and justice influenced legal thought, and his essays on private virtue offered consolation in a brutal age. Others, like the philosopher Martha Nussbaum, criticize him for rationalizing complicity. Advising Nero was not neutral—it legitimized tyranny. Seneca’s Stoic “detachment” becomes, in this view, a form of moral evasion.

A third interpretation sees Seneca’s contradictions as instructive. Pierre Hadot, the French historian of philosophy, argued that Seneca exemplifies the gap between philosophical ideals and lived reality. Stoicism aspires to perfect virtue, but humans are flawed. Seneca’s failures—his wealth, his compromises—make his successes more meaningful. He struggled to live philosophically in a world that punished it. That struggle, Hadot suggested, is the real subject of his writings.

Seneca’s enduring influence: from Marcus Aurelius to modern self-help

Despite the controversies, Seneca’s philosophical works have outlasted his political career. His Letters to Lucilius—124 essays on topics ranging from friendship to death—became a cornerstone of Stoic literature. Written in a conversational style, they offer practical advice: how to manage anger, face mortality, and find tranquility amid chaos. Seneca’s tone is personal, urgent, and accessible—qualities that appeal across centuries.

Marcus Aurelius, the emperor-philosopher who ruled a century after Seneca, absorbed his teachings. Meditations, Aurelius’s private reflections, echoes Seneca’s themes: the impermanence of life, the importance of self-discipline, the futility of external ambition. Aurelius, governing from military camps, found in Seneca a model of philosophical resilience.

During the Enlightenment, Seneca’s influence persisted. His critique of superstition and emphasis on reason appealed to thinkers like Diderot. His essays on nature—arguing that philosophy should study the cosmos to cultivate awe and humility—prefigured scientific attitudes.

In the 20th century, Seneca experienced a revival. Existentialists like Camus admired his confrontation with mortality. His essay On the Shortness of Life, which argues that we waste time on trivialities while fearing death, became a touchstone for modern reflections on time management and meaning. Self-help authors rediscovered Stoicism, citing Seneca’s advice on controlling emotions and focusing on what we can change.

His tragedies, though less read today, influenced Renaissance drama. Plays like Medea and Thyestes—marked by extreme violence, revenge, and psychological depth—shaped the conventions of Elizabethan tragedy. Shakespeare’s portrayal of ambition, guilt, and moral collapse owes a debt to Seneca’s dark theatricality.

Seneca also contributed to political philosophy. His concept of clementia—the ruler’s merciful restraint of power—anticipated debates about sovereignty and justice. Erasmus, writing in the 16th century, praised Seneca’s vision of the prince as moral exemplar, not absolute despot. Even critics of Stoicism, like Montaigne, engaged deeply with Seneca’s ideas, refining their own views through dialogue with his texts.

Conclusion

Seneca’s life is a study in contradiction—and perhaps that is why it endures. He climbed to power in the most dangerous court in the world, advocated philosophy while accumulating wealth, and died at the hands of the tyrant he had tutored. He justified a mother’s murder yet wrote movingly about conscience and virtue. He preached detachment but could not detach himself from the stakes of his time.

These contradictions do not invalidate his philosophy; they deepen it. Seneca did not write for ivory-tower theorists. He wrote for people navigating real pressures—ambition, fear, grief, temptation. His essays acknowledge human weakness, offering not perfection but progress. “It is not that we have a short time to live,” he wrote, “but that we waste a lot of it.” This insight, born from a life lived imperfectly, remains urgent.

Can a philosopher serve power without corruption? Seneca’s answer, implicit in his choices, is ambiguous. He believed engagement was necessary—that withdrawing from politics meant abandoning the world to worse actors. Yet his compromises suggest limits. There are betrayals no philosophy can rationalize, moments when proximity to tyranny becomes complicity. Seneca’s final act—suicide as philosophical demonstration—affirmed his principles, but it also underscored their cost. He died free, in a sense, but only because death was the last freedom left.

His writings survive because they speak to timeless struggles: how to live well in a flawed world, how to find meaning despite mortality, how to cultivate resilience when circumstances overwhelm us. Whether we judge Seneca the man harshly or sympathetically, Seneca the philosopher offers tools for living—imperfect, contradictory, but enduringly human.

Stoic concepts in Seneca’s thought

Virtue as the sole good: Seneca argued that only moral excellence—wisdom, courage, justice, temperance—constitutes true goodness. Wealth, health, and reputation are “preferred indifferents”: useful but not essential to happiness.

Dichotomy of control: A core Stoic teaching. We control our judgments, actions, and responses. External events—death, loss, others’ opinions—lie beyond our control. Anxiety arises from confusing the two.

Negative visualization: Seneca advised contemplating loss—of possessions, loved ones, life itself—to reduce attachment and appreciate the present. “All things human are short-lived and perishable,” he wrote in On the Shortness of Life.

Cosmopolitanism: Stoics saw themselves as citizens of the world, not just Rome. Seneca emphasized universal human dignity, arguing that slavery and social hierarchies were conventional, not natural.

Was Seneca a hypocrite?

Critics from Dio Cassius to modern scholars accuse Seneca of hypocrisy for reconciling vast wealth with Stoic ideals. His defense—that riches are morally neutral tools—strikes many as self-serving.

Yet some argue his position is philosophically coherent. Stoicism distinguishes between possession and attachment. A Stoic can own property without craving it, losing it without despair. Seneca’s wealth, by this logic, does not disprove his philosophy—unless he valued it above virtue.

The real test came with Nero’s matricide. Justifying that crime revealed not philosophical flexibility but moral failure. Seneca prioritized survival and influence over principle. Whether this makes him a hypocrite or a tragic realist depends on how we weigh ideals against the pressures of power.

Montaigne offered a sympathetic verdict: “Philosophy loses its edge when it comes to the rack.” Seneca’s compromises, Montaigne suggested, reflect the limits of reason when confronted with tyranny. Not an excuse, but perhaps an explanation.

Sources

Tacitus, Annals (primary source on Nero’s reign and Seneca’s death). Dio Cassius, Roman History (critical account of Seneca’s wealth and influence). Seneca, Letters to Lucilius, On the Shortness of Life, On Anger, On Clemency (collected essays and philosophical writings). Miriam Griffin, Seneca: A Philosopher in Politics (biography analyzing Seneca’s political career). Emily Wilson, The Greatest Empire: A Life of Seneca (recent scholarly biography). Pierre Hadot, Philosophy as a Way of Life (contextualizing Seneca within ancient philosophy). Martha Nussbaum, The Therapy of Desire (critical engagement with Stoic ethics). Suetonius, The Twelve Caesars (biographical details on Nero and imperial court).