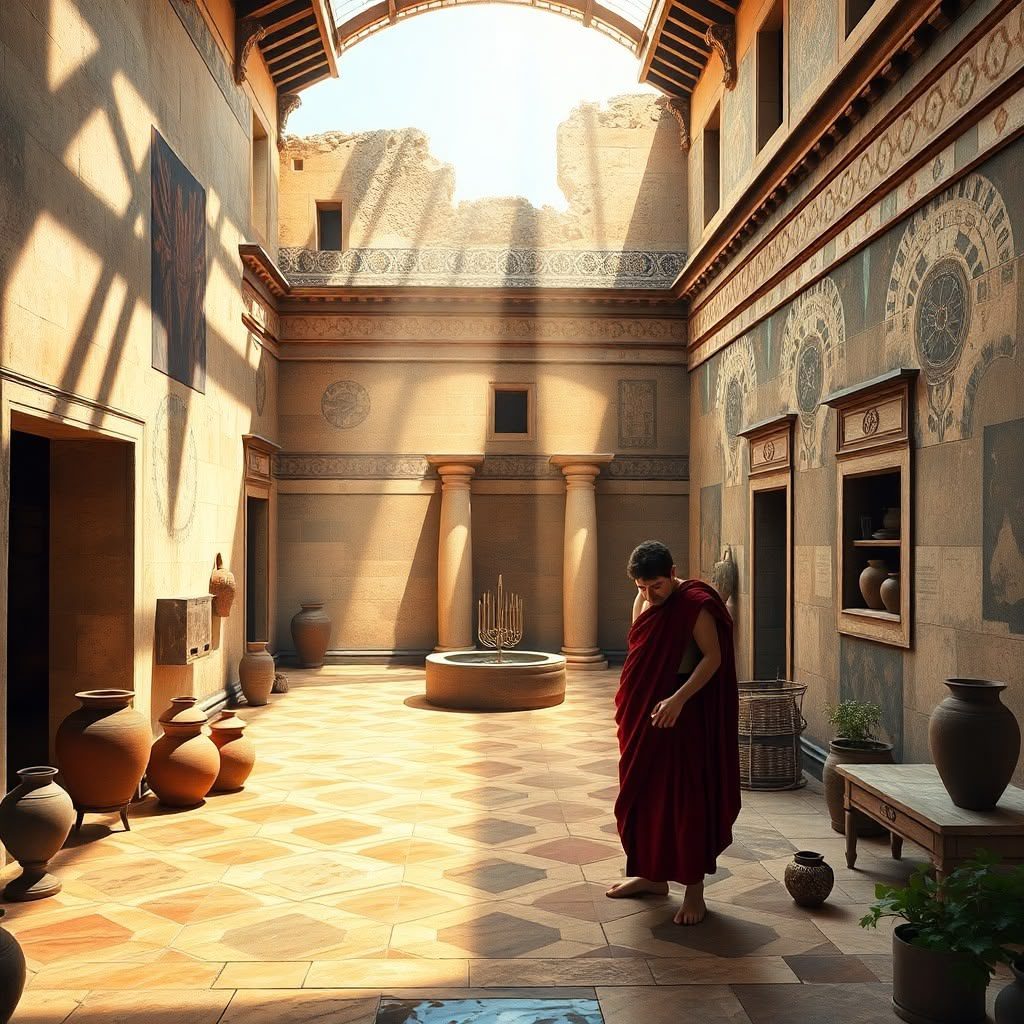

The morning light filters through the impluvium, casting geometric patterns across the atrium floor as a Pompeiian merchant prepares for the day ahead. He follows a routine established through generations—one that balanced productivity, connection, and wellbeing long before our modern obsession with optimization. This scene, frozen in volcanic ash for nearly two millennia, contains wisdom we’ve forgotten in our race toward technological advancement.

Pompeii’s destruction in 79 CE created an unparalleled time capsule of daily Roman life. Unlike historical texts that often glorify wars and emperors, Pompeii reveals something far more valuable—how ordinary people actually lived, worked, and found fulfillment. These weren’t mythological heroes but regular humans navigating their own complex world with remarkable ingenuity.

What makes this ancient knowledge so compelling isn’t its exotic nature but its startling familiarity. Today, we struggle with work-life balance, social connection, and finding meaning amid constant demands—the very challenges Pompeiians addressed through practical systems now buried beneath volcanic debris. Their solutions weren’t theoretical but battle-tested through generations of implementation.

The truth is both humbling and liberating: many of our “modern” problems were solved thousands of years ago by people without smartphones, productivity apps, or self-help books. Their intuitive approaches to household management, community engagement, and personal wellbeing often outperform our technology-driven alternatives. This isn’t about romanticizing the past but recognizing that human needs remain constant across millennia.

As we explore Pompeii’s hidden wisdom, you’ll discover how ancient practices can transform your daily experience. From morning routines that maximize natural energy cycles to social customs that deepen authentic connections, these forgotten techniques address the very gaps in modern living that leave us feeling perpetually overwhelmed and disconnected.

The Roman Home: Functional Design Beyond Aesthetics

The typical Pompeiian home wasn’t merely shelter but a multifunctional space designed with remarkable intentionality. Unlike our compartmentalized modern homes, the Roman domus integrated work, social life, and family activities within a unified architectural framework. This wasn’t accidental but reflected a holistic view of living that modern design often misses.

Central to every Pompeiian home was the atrium—an open-air courtyard that served as the heart of daily activities. This clever design harnessed natural light and ventilation while collecting rainwater through the impluvium (central pool). The significance goes beyond architectural innovation; it represents a fundamental principle of Roman living: bringing nature indoors. Today’s biophilic design movement essentially rediscovers what Romans knew intuitively—that incorporating natural elements into living spaces reduces stress and enhances wellbeing.

The Pompeiian home’s organization also reveals profound insights about balancing public and private life. The front sections (atrium and tablinum) were designed for business and receiving clients, while inner areas (peristylium and cubicula) provided family sanctuary. This intentional gradient from public to private created natural boundaries that protected family life while maintaining professional engagement—a separation many struggle to achieve in today’s work-from-home environment.

What might surprise modern visitors is the multifunctionality of Roman spaces. Rooms weren’t dedicated to single purposes but adapted throughout the day. The triclinium (dining room) might serve as meeting space by morning and entertainment venue by evening. This fluid approach to space utilization maximized the home’s utility while minimizing its footprint—a lesson in efficiency our larger but more rigidly defined modern homes could benefit from.

Storage solutions in Pompeiian homes demonstrate extraordinary practicality. Built-in wall niches, under-stair compartments, and clever furniture designs maximized limited space. The Romans understood that effective organization isn’t about having more storage but integrating it seamlessly into living areas. This principle could transform our modern relationship with possessions, focusing on intentional curation rather than endless accumulation.

Perhaps most remarkable was the Roman approach to household aesthetics. Wall paintings, mosaics, and decorative elements weren’t merely ornamental but served psychological functions. Garden scenes expanded perceived space, mythological imagery provided contemplative focus, and geometric patterns created order and harmony. This integration of beauty and function reminds us that our surroundings profoundly impact our mental state—a connection often overlooked in utilitarian modern design.

Time Without Clocks: Natural Rhythms and Productivity

The Roman relationship with time differed fundamentally from our modern obsession with precise measurement. Without mechanical clocks, Pompeiians organized their day according to natural rhythms and social conventions. The day was divided into twelve “hours” of daylight and twelve of darkness, with hour length varying by season. This flexible approach meant activities aligned with natural light patterns rather than arbitrary numerical divisions.

Morning routines in Pompeii followed the natural progression of daylight. The early hours (prima hora) were devoted to focused work requiring mental clarity. This intuitive approach aligns perfectly with contemporary chronobiology research suggesting our cognitive abilities peak in morning hours. By scheduling demanding tasks during their prima and secunda hora, Romans naturally optimized their cognitive resources without scientific understanding of circadian rhythms.

The Pompeiian workday incorporated natural breaks that modern productivity experts now champion. The midday pause for the prandium (light meal) and often a visit to the baths wasn’t viewed as interrupting productivity but as essential for sustained performance. This pattern resembles today’s evidence-based approaches like the Pomodoro Technique or 90-minute work cycles that acknowledge human attention naturally ebbs and flows.

Social time was integrated throughout the Roman day rather than relegated to evenings and weekends. Business discussions happened during morning salutatio (formal greeting of clients), exercise and networking occurred at the baths, and community connection happened naturally in public spaces. This integration prevented the stark work/life separation that often leaves modern professionals feeling fragmented between professional and personal identities.

Romans also maintained a fundamentally different relationship with leisure. Otium (purposeful leisure) wasn’t viewed as mere recovery from work but as essential for intellectual and spiritual development. Activities like philosophical discussion, artistic appreciation, and meaningful conversation were considered productive uses of time. This perspective challenges our modern tendency to view leisure as merely restorative rather than developmental.

Perhaps most profound was the Roman acceptance of seasonal variations in productivity. Winter naturally meant shorter workdays while summer allowed extended activity. Rather than fighting natural rhythms with artificial lighting and climate control, Pompeiians adapted their expectations and activities to environmental realities. This seasonal flexibility offers a compelling alternative to our attempt to maintain constant productivity regardless of natural cycles.

Food as Medicine: The Forgotten Wisdom of Roman Nutrition

The Roman approach to food combined practicality with sophisticated understanding of nutritional effects. Far from the excessive feasts portrayed in popular media, everyday Pompeiian meals demonstrated remarkable balance. The foundation of their diet—the Mediterranean triad of grain, olive oil, and wine—remains the basis of one of the world’s healthiest eating patterns. This wasn’t coincidental but reflected generations of observing food’s effects on health and vitality.

Breakfast in Pompeii (ientaculum) typically consisted of bread dipped in wine, fruit, and perhaps cheese—a simple combination providing sustained energy without overtaxing digestion. This practice aligns with modern research suggesting lighter morning meals support mental clarity. The main meal (cena) came later in the day when work demands diminished, allowing proper digestion and social connection. This timing respects the body’s natural digestive rhythms in ways our modern habit of eating heavily while still working often violates.

Preservation techniques in Roman kitchens reveal surprising sophistication. Without refrigeration, Pompeiians developed numerous methods to extend food usability: smoking meats, preserving fruits in honey, fermenting vegetables, and using salt and vinegar as natural preservatives. These techniques didn’t merely prevent spoilage but enhanced nutritional value. Fermentation, for instance, increases bioavailability of nutrients and provides probiotics—benefits only recently rediscovered by modern nutritional science.

Romans viewed food and medicine as overlapping categories rather than separate domains. Common kitchen ingredients doubled as remedies: garlic for infection, mint for digestion, honey for wound healing. This integrative approach represents a more holistic understanding of health than our modern separation of nutrition and medicine. The Roman cookbook wasn’t just about flavor but about maintaining wellbeing through daily choices.

Meal preparation in Pompeiian homes balanced efficiency with nourishment. Many homes feature food preparation areas with clever design elements: counter heights optimized for standing work, built-in storage for common ingredients, and multipurpose cooking vessels. The process prioritized simple preparation methods that preserved nutritional value while minimizing labor—a balance modern cooking often sacrifices to either convenience or complexity.

Perhaps most striking was the social dimension of Roman eating. Meals weren’t rushed refueling stops but essential social experiences. The triclinium dining arrangement, with couches positioned to facilitate conversation, physically structured meals around human connection. This integration of nourishment and relationship acknowledges that how we eat significantly impacts digestion and satisfaction—a connection increasingly validated by research on mindful eating and the social determinants of health.

The Social Network: Community Before Technology

Pompeii’s elaborate social fabric reveals sophisticated systems for maintaining connection long before digital networks. The city’s physical layout prioritized interaction through intentional design—forum spaces, neighborhood shrines, public bathhouses, and street-facing shops created natural gathering points. This architectural promotion of spontaneous encounter stands in stark contrast to modern suburban isolation where interaction requires deliberate scheduling.

The Roman patronage system established reciprocal responsibility networks that provided social security without bureaucratic administration. Clients received protection and opportunities from patrons who gained support and status through their client network. While hierarchical by nature, this arrangement created mutual obligation bonds that ensured resources flowed throughout the community. The morning salutatio ritual—where clients greeted patrons—wasn’t merely ceremonial but reinforced these vital connections daily.

Neighborhood identity played a crucial role in Pompeiian social cohesion. Each vicus (neighborhood) maintained its own protective deities, celebrations, and communal spaces. Local shrines at street intersections (compitum) served as gathering points for both religious observance and practical matters. This localized identity created manageable social units within the larger urban environment—an approach that addresses the anonymity problem plaguing many modern cities.

The Roman approach to friendship (amicitia) involved clearly defined expectations and responsibilities rather than the often ambiguous connections of modern social networks. Friendships were categorized and cultivated according to their depth and function, with different levels of intimacy appropriate to each category. This pragmatic approach to relationship management prevented the social exhaustion many experience today when attempting to maintain uniform intimacy across expanded digital networks.

Public dining and drinking establishments in Pompeii weren’t merely commercial ventures but essential social infrastructure. The taberna (bar) and thermopolium (food counter) served as information exchanges and relationship maintenance spaces. Unlike modern restaurants designed for private dining experiences, these establishments encouraged interaction between patrons through shared seating and open layouts. They functioned as third places—neither home nor work—where community bonds could be reinforced through regular informal contact.

Perhaps most revealing is how Romans handled social conflict. Public reputation (dignitas) was carefully managed, but confrontation followed established protocols. Disagreements were often addressed through intermediaries or within appropriate contexts rather than through direct confrontation. This sophisticated approach to conflict management preserved relationships while allowing legitimate grievances to be addressed—a balance many modern interactions fail to achieve.

Mind and Body: The Integrated Wellness Philosophy

Roman wellness practices rejected the mind-body dualism that often fragments modern health approaches. For Pompeiians, physical, mental, and social wellbeing were inseparable facets of a unified whole. This integration appears most vividly in the bathhouse culture that combined hydrotherapy, exercise, learning, and socializing within a single institution. The progression through tepidarium (warm room), caldarium (hot room), and frigidarium (cold plunge) parallels modern contrast therapy techniques now gaining scientific validation.

Exercise in Roman culture wasn’t isolated from daily life or focused primarily on appearance. Physical activity occurred within social contexts—the palaestra (exercise ground) facilitated both movement and connection. The emphasis on functional movements rather than isolated muscle development created practical strength for daily activities. This integrated approach contrasts sharply with modern exercise often performed in isolation on machines designed for muscles rather than movements.

The Roman understanding of mental health recognized the essential role of meaning and purpose. The concept of gravitas valued emotional regulation and perspective-taking rather than unrestrained expression. Regular contemplative practices, often integrated into daily rituals, promoted what we would now call mindfulness. These weren’t separate “wellness activities” but woven into the fabric of daily experience—from morning household shrine observances to evening reflection periods.

Sleep patterns in Pompeii aligned more naturally with circadian rhythms than our modern habits. Without artificial lighting, activities gradually quieted with sunset, and sleeping environments remained cooler and darker than many modern bedrooms. The common practice of afternoon rest during summer heat (similar to the siesta) acknowledged the natural midday energy dip many fight through with caffeine today. These patterns respected biological realities rather than imposing industrial schedules on human physiology.

Preventative health measures featured prominently in Roman daily habits. Regular bathing, use of oils for skin protection, careful attention to water quality, and seasonal dietary adjustments all reflected sophisticated understanding of environmental health factors. The Roman emphasis on clean public water systems through aqueducts and public fountains demonstrated recognition that community health required infrastructure investment—a principle sometimes overlooked in modern individualistic health approaches.

Perhaps most striking was the Roman approach to aging. Elder members remained integrated in household and community life rather than segregated by age. Their experience was valued, and their continued contribution expected. This integration provided both purpose for older individuals and wisdom transfer to younger generations—addressing simultaneously the isolation many seniors experience today and the disconnection from traditional knowledge many younger people feel.

Applying Ancient Wisdom to Modern Challenges

The practical applications of Pompeiian wisdom begin with reconsidering our living spaces. The Roman principle of bringing nature indoors can transform modern environments through strategic use of natural light, indoor plants, water features, and natural materials. Even modest changes—placing workspaces near windows or incorporating living plants—can significantly impact wellbeing. The Roman gradient from public to private spaces suggests rethinking open floor plans to create transition zones that buffer work and relaxation areas.

Our relationship with time can be transformed through Roman rhythmic awareness. Aligning demanding cognitive tasks with natural morning energy peaks rather than arbitrary scheduling improves performance without additional effort. Building in purposeful midday breaks—even brief ones—acknowledges natural attention cycles. Seasonal adjustment of expectations, working with rather than against environmental conditions, reduces the friction between natural rhythms and imposed schedules.

Modern eating patterns particularly benefit from Roman insights. Simplifying breakfast to easily digestible components supports morning clarity. Treating food preparation as an integrated part of daily rhythm rather than an inconvenient interruption changes our relationship with nourishment. Exploring traditional preservation methods like fermentation adds both flavor dimension and probiotic benefits to modern diets. Perhaps most importantly, reclaiming mealtime as social connection opportunity rather than mere refueling transforms both digestion and relationship quality.

Community connection can be fostered through intentionally creating modern equivalents of Roman gathering spaces. Participating in neighborhood-scale organizations builds the intermediate social structures often missing between isolated households and anonymous mass society. Developing clearer relationship categories with appropriate expectations—similar to Roman amicitia gradations—prevents social exhaustion while ensuring appropriate investment in core relationships. Regular engagement with intergenerational groups provides both perspective and knowledge transfer that age-segregated activities lack.

Wellness integration following Roman examples means reconsidering how we separate health domains. Combining social interaction with physical activity—walking meetings, group exercise, active hobbies with friends—builds multiple dimensions of wellbeing simultaneously. Incorporating brief contemplative practices into existing daily transitions rather than adding separate meditation sessions makes mindfulness sustainable. Respecting natural sleep patterns by reducing evening light exposure and allowing seasonal variations in rest needs aligns with rather than fights biological reality.

The wisdom of Pompeii isn’t about historical reenactment but extracting principles that remain relevant across millennia. These approaches worked because they aligned with fundamental human needs and natural patterns that haven’t changed despite our technological advancement. Their effectiveness doesn’t require rejection of modernity but thoughtful integration of ancient insights with contemporary understanding.

The Timeless Human Experience

What makes Pompeii’s preserved wisdom so powerful is the recognition of our shared humanity across time. The Pompeiian merchant concerned with maintaining his social network, managing his household, and finding daily meaning faces challenges remarkably similar to our own. The solutions developed through generations of practical experience weren’t theoretical but tested through implementation in real households navigating real challenges.

This connection across millennia offers both humility and hope. Humility in recognizing that many of our “modern” problems and solutions have precedents in ancient wisdom; hope in discovering that human ingenuity has repeatedly found pathways to balanced living across vastly different technological contexts. The Pompeiian example reminds us that fulfillment doesn’t depend primarily on technological advancement but on alignment with fundamental human needs and natural patterns.

The volcanic ash that tragically ended Pompeiian life paradoxically preserved its wisdom for our benefit. As we face increasing disconnection from natural rhythms, community bonds, and integrated wellbeing, these ancient practices offer not regression but remembrance of patterns aligned with our essential nature. Their implementation doesn’t require abandoning modern advantages but incorporating timeless principles into contemporary contexts.

In your own daily experience, consider what Pompeiian wisdom might most directly address your current challenges. Is it their approach to integrating nature into living spaces? Their rhythmic relationship with time? Their community maintenance practices? Their unified approach to wellbeing? The most powerful application comes not from wholesale adoption but thoughtful integration of specific principles into your particular circumstances.

The citizens of Pompeii couldn’t have imagined their daily practices would provide guidance two millennia later. Yet in their ordinary routines, preserved through extraordinary circumstances, we find not exotic historical curiosities but practical wisdom for addressing the very human challenges we continue to face. Their legacy isn’t just in preserved buildings and artifacts but in demonstrating patterns of living that remain relevant across the vast expanse of human experience.