The Colosseum stands as a testament to Roman engineering brilliance—a 2,000-year-old monument that has survived earthquakes, plundering, and the merciless passage of time. Yet today, this architectural marvel faces its most insidious threat: our own well-intentioned efforts to save it.

In 2018, conservators discovered that sections of the Colosseum restored in the 1990s were deteriorating faster than untouched areas. The culprit wasn’t pollution or tourists, but the very cement mixtures applied to “strengthen” the ancient structure. The modern materials, chemically incompatible with the original Roman concrete, had triggered accelerated degradation that threatened to undermine decades of preservation work.

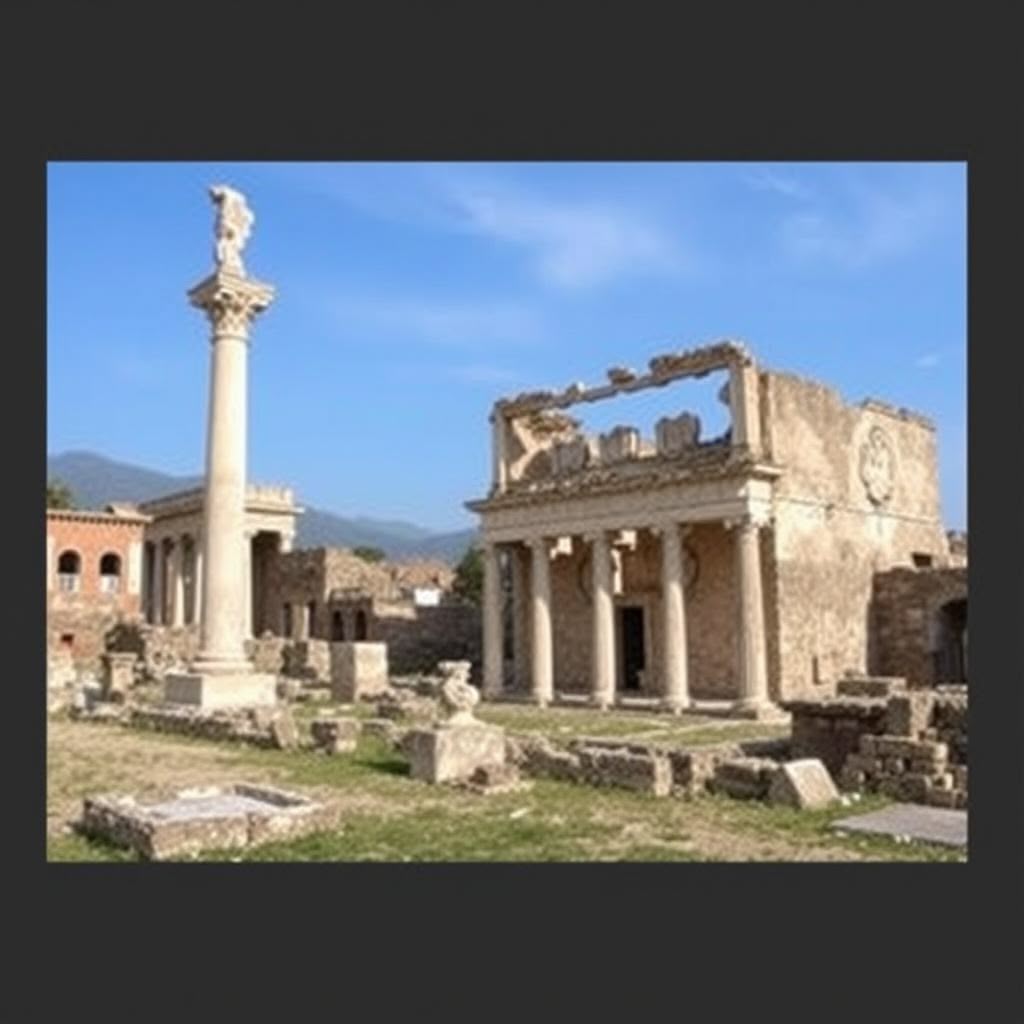

This isn’t an isolated incident. Across Italy’s archaeological landscape, similar scenarios are unfolding in alarming silence. From the crumbling walls of Pompeii to the deteriorating aqueducts that once supplied Rome with water, conventional preservation techniques are creating a preservation paradox—often doing more harm than good.

“We’re witnessing a quiet crisis in Roman monument conservation,” explains Dr. Elena Russo, archaeological conservator at the University of Rome. “The preservation approaches developed in the 20th century simply aren’t compatible with the unique properties of Roman construction. We’re essentially watching these irreplaceable monuments being damaged by the very methods intended to protect them.”

The Preservation Paradox: When Protection Becomes Destruction

The Romans built for eternity. Their innovative concrete—a mixture of lime, volcanic ash, and seawater—actually strengthens over time through a remarkable chemical process unknown until recently. When exposed to seawater, this concrete undergoes a transformation where the volcanic ash reacts with seawater to create aluminous tobermorite and phillipsite, minerals that strengthen the concrete’s matrix.

Modern Portland cement, developed in the 19th century and now the world’s most widely used building material, operates on fundamentally different chemical principles. When modern restoration projects apply these materials to ancient structures, they create a preservation time bomb.

At Pompeii, this incompatibility manifested dramatically in 2010 when the House of the Gladiators collapsed despite—or perhaps because of—recent restoration work. Investigators later determined that modern concrete used in roof repairs had created excess weight and trapped moisture, compromising the ancient structure’s integrity. The modern materials, impermeable compared to the breathable Roman mortars, had essentially suffocated the building from within.

The preservation paradox extends beyond material incompatibility. Consider the Arch of Septimius Severus in the Roman Forum. In the 1980s, conservators applied water-repellent treatments to protect the monument from acid rain. Thirty years later, these treatments had degraded, creating a hydrophobic barrier that prevented natural evaporation. Moisture became trapped within the stone, accelerating salt crystallization and causing extensive surface flaking that continues today.

The Tourism Tightrope: Balancing Access and Preservation

Italy’s cultural heritage sites welcome over 50 million visitors annually, with the Colosseum alone receiving over 7 million tourists in pre-pandemic years. This tourism generates essential revenue—approximately €400 million yearly—but creates immense preservation challenges.

Dr. Marco Fabbri, director of archaeological conservation at Sapienza University, describes this as “the conservation conundrum.” “Every footstep across these ancient floors contributes microscopic damage,” he explains. “The moisture from human breath inside enclosed spaces like the Domus Aurea creates perfect conditions for harmful microbiological growth. Yet without tourism revenue, we lack the funds to protect these sites.”

The Baths of Caracalla exemplify this dilemma. When opened to tourism in the 1980s, the site’s delicate mosaic floors were exposed to thousands of daily visitors. Despite installing elevated walkways in the 1990s, constant vibrations and humidity changes have accelerated tessera detachment. The very features that make the site appealing to visitors are gradually disappearing because of their presence.

Traditional solutions have proven inadequate. At Herculaneum, conservators installed plexiglass barriers to protect fragile wall paintings. Within a decade, these barriers had created microenvironments where condensation accumulated, promoting mold growth that damaged the very frescoes they were meant to protect.

The Environmental Assault: Climate Change Versus Ancient Stone

The Mediterranean climate that once helped preserve Rome’s monuments has transformed into an environmental assault. Climate scientists have documented a 1.5°C temperature increase in Rome since the 1950s, accompanied by increasingly volatile weather patterns that Roman architects never anticipated.

The Pantheon, with its remarkable dome and oculus open to the elements, was designed to handle rainfall through sophisticated drainage systems. But these systems now face unprecedented challenges. In 2020, flash flooding overwhelmed these ancient drains, submerging portions of the marble floor and accelerating salt efflorescence in the lower walls.

“Roman engineers designed these structures for a climate that no longer exists,” notes climatologist Sophia Ricci. “The alternating extreme drought and deluge cycles we’re experiencing create expansion-contraction patterns in the stone that weaken structural integrity at a microscopic level.”

At Ostia Antica, Rome’s ancient port city, rising sea levels have elevated the groundwater table, pushing destructive salts into the masonry of structures that had remained stable for centuries. Traditional waterproofing treatments have proven counterproductive, trapping salts within the walls and accelerating deterioration.

Conventional preservation responses have typically involved applying synthetic consolidants to strengthen weathered stone surfaces. However, research at the Roman site of Baalbek in Lebanon demonstrated that many of these treatments become brittle and crack under intensifying UV radiation, creating pathways for water infiltration that accelerate, rather than prevent, damage.

The Chemical Mismatch: Modern Materials Versus Ancient Ingenuity

Perhaps the most fundamental failure in Roman monument preservation stems from a profound misunderstanding of Roman building technology. For centuries, we believed Roman concrete was simply an inferior precursor to modern formulations. This assumption led conservators to “improve” ancient structures with contemporary materials, inadvertently initiating chemical warfare at a molecular level.

The Pons Aemilius, Rome’s oldest stone bridge dating to 142 BCE, received extensive restoration in the 1960s using epoxy resins to strengthen cracked stones. These resins, with significantly different thermal expansion properties than the original materials, created internal stresses during temperature fluctuations. Within decades, these “strengthened” sections began failing at higher rates than untreated areas.

Dr. Camilla Venturi of the Roman Concrete Project explains: “Modern concrete cures through a completely different chemical process than Roman concrete. When we apply these materials to ancient structures, we’re essentially forcing incompatible building technologies to coexist. The resulting chemical and physical stresses inevitably lead to accelerated deterioration.”

This chemical mismatch extends to cleaning methods. The travertine facades of the Temple of Antoninus and Faustina in the Roman Forum were cleaned in the 1980s using ammonium bicarbonate poultices. While effective at removing pollutant crusts, this treatment altered the stone’s protective patina, making it more vulnerable to modern pollution. Today, these cleaned sections show significantly more deterioration than areas that remained untreated.

Innovative Solutions: Learning from Roman Builders

The path forward requires both technological innovation and philosophical recalibration. Recent breakthroughs in understanding Roman concrete offer promising alternatives to destructive conventional approaches.

At the harbor installations at Caesarea Maritima in Israel, archaeologists and materials scientists collaborated to analyze the remarkably durable Roman maritime concrete that has withstood 2,000 years of Mediterranean wave action. By identifying the unique mineral phases formed when seawater interacts with the volcanic components of Roman concrete, they developed a modern analog that mimics the ancient material’s self-strengthening properties.

When this Roman-inspired concrete mixture was tested in restoration work at the Theater of Marcellus in Rome, the results were remarkable. After five years, the treated sections showed perfect integration with the ancient material, with no detachment, cracking, or chemical incompatibility issues that typically plague conventional restoration materials.

“We’re not reinventing the wheel,” says concrete specialist Dr. Alessandro Bianchi. “We’re rediscovering what the Romans already knew. Their concrete wasn’t primitive—it was sophisticated in ways we’re only beginning to understand. By humbling ourselves to learn from ancient builders rather than imposing our modern solutions, we’re developing preservation approaches that work with, not against, these monuments.”

Digital Conservation: Preserving Without Touching

Another promising frontier involves minimal-intervention strategies supported by advanced documentation. The Domus Aurea, Nero’s legendary golden palace, faced severe structural issues after centuries buried beneath later construction. Rather than attempting comprehensive physical restoration, conservators employed targeted structural stabilization combined with augmented reality.

Visitors now experience the splendor of the original space through digital reconstruction, while the physical structure receives only necessary stabilization using compatible materials. This approach minimizes the introduction of modern materials while enhancing the visitor experience.

Similar approaches at Villa Adriana in Tivoli use 3D mapping to monitor microscopic changes in the structure, allowing conservators to intervene only when absolutely necessary and with precisely targeted treatments. This “conservation minimalism” represents a philosophical shift from aggressive restoration toward thoughtful preservation.

Biological Solutions to Chemical Problems

Perhaps the most revolutionary developments come from biomimetic approaches to conservation. At the Temple of Bacchus in Baalbek, conservators experimented with calcium carbonate-precipitating bacteria to heal cracks in ancient limestone. These microorganisms, applied in a nutrient solution, naturally deposit calcium carbonate—essentially the same material as the limestone itself—in fissures and erosion zones.

The results have been exceptional. Unlike synthetic consolidants that create hard, impermeable barriers, these biological treatments integrate perfectly with the original material, maintaining its porosity and weathering characteristics. Five years after application, treated areas remain stable while untreated control sections continue to deteriorate.

“Nature has been preserving stone for billions of years,” notes microbiologist Dr. Francesca Totti. “By harnessing natural processes rather than fighting them with synthetic chemicals, we’re developing preservation approaches that are both more effective and more sustainable.”

The Path Forward: A New Preservation Philosophy

Saving Rome’s monuments requires more than technical innovation—it demands a philosophical reset in our approach to preservation. The conventional Western conservation paradigm, which often prioritizes returning monuments to an idealized “original” state, has proven particularly damaging for Roman structures.

Dr. Lucia Romano, head of the Roman Monuments Initiative, advocates for a preservation approach she calls “historical continuity” that recognizes these monuments not as frozen artifacts but as living structures with ongoing histories.

“The Colosseum isn’t simply a first-century structure—it’s a monument that has evolved over two millennia,” she explains. “When we try to restore it to some ‘original’ state, we’re actually creating a historical fiction while destroying authentic material. The 19th-century restoration work on the Colosseum is itself historically significant. Our job isn’t to erase that history but to preserve the monument in all its complex chronological layers.”

This philosophical shift has practical implications. At the Basilica of Maxentius, conservators recently chose to stabilize and protect fallen architectural elements in their collapsed positions rather than attempting reconstruction. This approach preserves archaeological integrity while allowing visitors to understand the true condition of these ancient structures.

Some of the most successful preservation projects have embraced this philosophy of minimal intervention. The recent work at the Tomb of Raphael in the Pantheon focused on environmental control and monitoring rather than aggressive material treatments. By stabilizing temperature and humidity fluctuations, conservators addressed the root causes of deterioration without introducing potentially harmful modern materials.

The Economic Reality: Sustainable Preservation

Effective preservation requires sustainable funding models. The traditional approach—charging admission to generate restoration funds—creates a destructive cycle where increased tourism drives increased deterioration, necessitating more invasive (and often harmful) restorations.

Innovative public-private partnerships offer alternative models. The successful restoration of the Trevi Fountain, funded by the fashion house Fendi, demonstrated how corporate sponsorship can support preservation when properly structured. The project employed minimally invasive techniques, used compatible materials, and established a maintenance endowment that reduces the need for major interventions.

Digital technologies offer additional funding pathways. The Roman Forum’s virtual reconstruction app generates revenue from remote visitors worldwide, supporting physical conservation while reducing on-site tourism pressure. This “preservation through digitization” approach allows millions to experience Rome’s monuments without contributing to their physical deterioration.

Conclusion: Preserving Rome’s Legacy for Future Generations

The monuments of ancient Rome have survived for two millennia not because they were frozen in time but because they adapted. Their materials responded to environmental changes, developing protective patinas and natural equilibrium with their surroundings. Our preservation approaches must mirror this adaptability.

The evidence is clear: conventional preservation techniques developed in the industrial age are failing Rome’s ancient monuments. The path forward requires humility—acknowledging that Roman builders possessed sophisticated knowledge we’re only beginning to rediscover—and innovation that works with, not against, these ancient structures.

By embracing biomimetic solutions, minimal intervention philosophies, and sustainable funding models, we can ensure these monuments survive not just as tourist attractions but as authentic connections to our shared human past. The Romans built for eternity. Our preservation approaches must honor that ambition by thinking beyond the quick fixes that have proven so destructive.

As Dr. Romano reminds us: “These monuments have survived for 2,000 years. Our responsibility isn’t just to preserve them for our generation, but to ensure they endure for the next 2,000 years. That requires both technological innovation and philosophical wisdom—learning from the past to protect the future.”

The silent collapse of Rome’s monuments can be halted, but only if we have the wisdom to sometimes do less, not more—to preserve rather than restore, to understand rather than impose, and to work with the ingenious materials and methods that have already proven their durability across millennia.